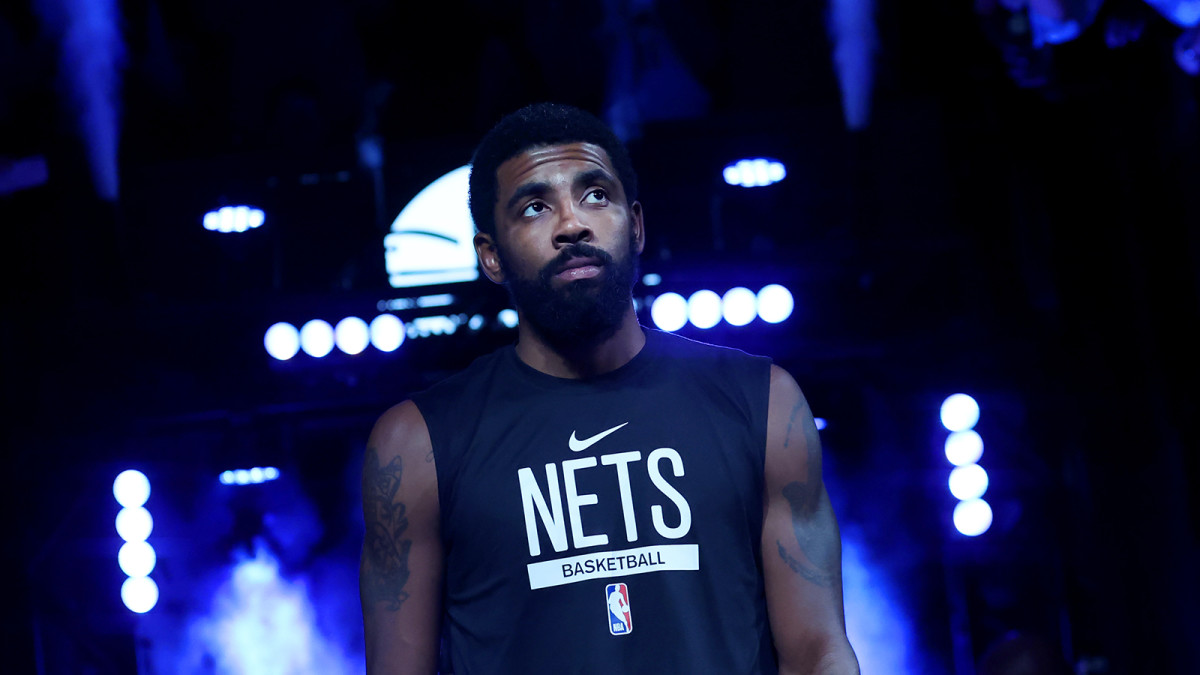

After five days, a number of convoluted equivocations and explanations, and effectively fueling a spark into a full-scale public-relations inferno, the Brooklyn Nets took the step of suspending star guard Kyrie Irving for at least five games after he essentially dug his heels in and refused to apologize for linking and sharing a film that included deeply antisemitic beliefs and attitudes.

Coincidentally, hours after the team announced it was suspending Irving by saying he was “currently unfit to be associated with the Brooklyn Nets,” Irving apologized in a lengthy statement. “To All Jewish families and Communities that are hurt and affected from my post, I am deeply sorry to have caused you pain, and I apologize,” he wrote.

It was what should have taken place days earlier. And perhaps it’s what would have happened sooner if the league itself hadn’t taken such a passive half-measure toward the issue to begin with.

As the league comes out of one of its worst two-month stretches in recent memory, it’s hard not to have that takeaway here: that Adam Silver and the association—at times, viewed as the closest thing to a morally progressive compass in American pro sports—aren’t putting their feet down forcefully enough to send a message about what is and isn’t acceptable.

In the days before the Nets took the step of suspending Irving, the NBA and its players union each released statements condemning antisemitism, but each statement was toothless and failed to mention Irving by name. On Thursday, realizing the problem wasn’t going away, Silver, who is Jewish, issued a statement expressing his disappointment that Irving hadn’t “offered an unqualified apology and more specifically denounced the vile and harmful content contained in the film he chose to publicize.” He said he planned to meet with Irving over the next week to discuss it all.

But in a way, Silver’s comment—which was essentially washed out shortly after anyway, when Irving declined several opportunities to answer a yes-or-no question about whether he held antisemitic beliefs—was late, and seemingly not enough. And it felt reminiscent of the last big controversy that was put before the league back in September.

Just as training camps were getting set to open throughout the NBA, the league announced it would be fining Phoenix Suns and Mercury owner Robert Sarver $10 million and suspending him for one year as a result of investigative findings that concluded he’d fostered a toxic workplace culture.

The penalty seemed to leave most players and league observers frustrated, given that more than 100 people interviewed during the investigation reported conduct that violated workplace standards. He used the n-word at least five times (including four times after being told it wasn’t appropriate), told a pregnant employee she wouldn’t be able to do her job effectively upon becoming a mother and passed a female employee in the hallway and asked whether she “got an upgrade” following a breast augmentation, among scores of other troubling instances.

The sheer absurdity of some of the details raised a question: If this conduct—and more than 100 people attesting to it—can’t get you barred from the league, what can? Or does it essentially have to be a smoking gun, the way the Donald Sterling situation was?

Silver and the league were fortunate that players like LeBron James, Chris Paul and Draymond Green were highly vocal, along with sponsors like PayPal, which threatened to cut ties if Sarver remained. They effectively pushed Sarver to decide he’d seek to sell the club. But only after the league’s punishment struck so many as being too light, given the message it sent. Silver recently went to Phoenix to apologize to Suns employees for Sarver’s harassment. “To the extent you feel let down by the league, I apologize. I take responsibility for that,” he told them.

The fiasco with Sarver illustrated that the league’s players—almost three-quarters of whom are Black—often hold stronger, more progressive views on a handful of political issues than the league office does. Yet when the NBA’s morality is discussed, the groups are usually discussed interchangeably, as if they’re one and the same. (It raises a fair question here, too: Why have none of the players spoken up on the Irving issue? Is it that they’re reluctant to call out one of their own, even on an issue as serious as this? And does the lack of momentum from the players here inform why the Nets and the NBA were so slow about enforcing a punishment?)

Over time, there have been a handful of instances in which the league’s players have embraced a cause or stance far more quickly than Silver has.

Back in 2014, Derrick Rose wore a T-shirt that spelled out “I Can’t Breathe” in the aftermath of Eric Garner’s death at the hands of police, prompting a number of players throughout the league to follow suit. In response, Silver said he respected the players’ decisions to wear the shirts, but that he preferred that they wear their normal attire for warmups “to abide by our on-court rules.” Similarly, after Colin Kaepernick became a flashpoint in the NFL for kneeling during the national anthem in ’16, Silver said he hoped NBA players would stand during anthems to stay in tune with the league’s rule around that issue. (He again said he respects players’ freedoms of expression, but that he prefers the anthem to be a time to showcase unity.) And back in ’19, after the Raptors won the title and Toronto executive Masai Ujiri—trying to go on to the court to celebrate—was shoved twice by an Alameda County sheriff’s deputy, Silver said in an interview “those are the kinds of situations [Ujiri] needs to learn to avoid.” His comments came off poorly after the deputy dropped his lawsuit against Ujiri, as video evidence of the incident seemed to vindicate the executive. Silver has since apologized to Ujiri, both publicly and privately.

Back when Silver was at the beginning of his tenure as commissioner, it was easier to conflate the league’s stance with the stances its players took. In his first memorable act as the NBA’s chief, Silver, a lawyer by trade, was decisive and dropped the hammer on Sterling, who’d been recorded making racist remarks. The ruling could’ve led to a nasty legal battle, but the league dodged that bullet when Sterling was ruled mentally unfit, which allowed his wife, Shelly, to oversee the sale of the team.

The swift decision won Silver acclaim from all corners of the league, and rightfully so: Racism is bad, and anyone worth their weight in salt can acknowledge that it shouldn’t have a place in the league. Which was why the initial punishment for Sarver—much like the delayed punishment with Irving—was off-putting to so many.

And the timing of all this is magnified, as a number of the story lines floating around the NBA the last couple months have been ugly.

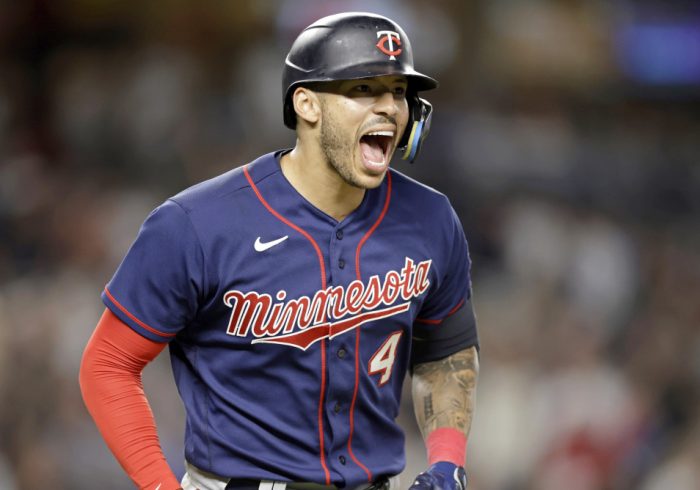

There was Anthony Edwards, the Timberwolves’ star and 2020 No. 1 pick, posting a homophobic video to Instagram while driving past and laughing at members of the LGBTQ community in Minneapolis. (He later apologized for the incident and was fined $40,000 by the league.)

There was the Celtics’ suspending Ime Udoka, the coach who led the club to a stunning turnaround and to the NBA Finals in his first year at the helm, after an investigation revealed he’d had an improper relationship with a female subordinate, and that he’d reportedly made unwanted comments toward her at some point. And while Brad Stevens and the Celtics expressed frustration with the unwarranted attention the Udoka speculation brought on the women in the organization, the club announced it’d be elevating assistant Joe Mazzulla to the head seat—a choice that, to some, was tone deaf, given that Mazzulla had been charged with domestic battery after grabbing a woman by the neck back in 2009 during his time in college.

Then there’s the issue that first hit the news last week, but now seems like it could become a much bigger story in the coming months: The Spurs abruptly waived 2021 lottery pick Josh Primo, who allegedly repeatedly exposed himself to women in the organization.

While the decision was shrouded in mystery when it was first announced—the Spurs had just picked up his contract option, and after being waived Primo put out a vague statement saying he was going to take time to focus on his mental health—the picture appears to be getting clearer now, and it isn’t pretty. On Thursday, a former clinical psychologist for the team filed suit against the organization and Primo himself. She accused the team of ignoring her reports of Primo’s indecent exposure and says the team has known about Primo’s misconduct dating back to January. (In a statement, Spurs CEO R.C. Buford said the club disagrees with the details, facts and timeline laid out in the lawsuit. Primo’s attorney, William J. Briggs II, said Primo “never intentionally exposed himself to her or anyone else,” and the doctor “did not bother to tell her patient that his private parts were visible underneath his shorts.”)

While there sometimes isn’t much more the league can or should do in response to certain things—the Edwards situation, for example—it will be worth watching how the Primo scenario shakes out, particularly if the Spurs are investigated and found to have known about the situation for nearly 10 months without acting. If they moved to cut only Primo once there was the imminent threat of a lawsuit, there should be major consequences, the sort Silver has rarely had to hand down on a team scale, let alone to an organization like the Spurs.

All of this isn’t to suggest Silver and the league never get moral, big-picture things right. Back in 2016, the NBA moved the All-Star Game out of North Carolina to protest a state law that limited anti-discrimination protections for the LGBTQ community. And when the Bucks kick-started a process to stage a strike during the playoffs in the bubble back in ’20 following the police shooting of Jacob Blake, NBA officials worked alongside players to broaden social and political efforts—both to open a number of arenas as polling places, but also to get the players themselves to vote. (The percentage of players registered to vote increased from 22% to 96% in ’20, according to the players union.) That same year, in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd, the league’s owners committed to donating $300 million over the next 10 years toward efforts to close the socioeconomic gaps caused by systemic racism in America.

Thanks to the swift action taken in the Sterling incident, there’s at least some track record of Silver and the league taking the appropriate measure when necessary.

But when the league faces similar challenges in the future, it’d be nice to see Silver and league act decisively, as opposed to waiting on the players and sponsors to do that difficult work for them.

More NBA Coverage: