The banner is visible but not necessarily prominent. It hangs near a corner of the Levi’s Stadium home locker room, in an otherwise blank space between two lockers. On a white background five years are spelled out in red numbers—1981 to ’94—each connoting a season in which San Francisco won a Super Bowl. It’s understated yet powerful, a reminder of what was and what matters and what, they hope, may be again.

Only two franchises—Pittsburgh and New England—have won more championships in the Super Bowl era (and only Dallas can match the 49ers’ five titles). But that last year on the banner grows more concerning with each championship-less campaign. Most pro football franchises would kill for this franchise’s uniquely rich history. But despite 12 playoff appearances since seizing their last Lombardi Trophy, despite a close Super Bowl loss, late, three seasons ago, the 49ers are now almost three decades removed from the dominance that long defined them.

Perhaps that’s why the locker room mood late Saturday wasn’t festive, not even after a 41–23 throttling of the Seahawks that featured 25 consecutive second-half points. The vibe—which could be described as a marriage between insurance conference and Mondays at the office—stemmed from what’s ahead, from how hard it is to win the season’s final game, how much preparation and health and luck are required, from all the strange and glorious and extra this season has presented. In the end these 49ers will end up looking at the same banner they’ve seen for months … or adding another year to it.

If any players smiled, the grin was discreet. If any coaches loved their team’s performance, they told only themselves. As cornerback Charvarius Ward answered questions at his locker, he wore several silver chains and a cross around his neck. They glimmered. He yawned—like, actually yawned. “It feels great,” he said.

The team’s play was far more convincing than Ward’s answer. Had those crowded around him not just watched San Francisco bludgeon its division rival, it’s unlikely that a single person listening would have believed him.

In a season of disbelief that San Francisco first stoked and then dismantled, what the 49ers are doing just doesn’t make a ton of sense. Start with the spate of injuries early on. Add in the resulting 3–4 start. Plus the musical chairs at quarterback, which required schematic adjustments to tailor the offense to Trey Lance (broken ankle, Week 2), then Jimmy Garoppolo (broken foot, Week 13), then Brock Purdy (the Faithful, as they call themselves, might want to find some wood). Throw in the fair and relevant notions that San Francisco, despite a complete, star-studded roster, was doomed to another lost season—that they lacked a championship-level quarterback, that Mike McDaniel’s departure to Miami was sinking the offense, that the Niners couldn’t stay healthy—hovering overhead.

San Francisco didn’t simply untangle those sentiments; they took a sledgehammer to them, then shoved the remnants into a trash compactor, then turned that into something more like … gold. In came Christian McCaffrey, the shifty, versatile running back from Carolina. Back came many of the 49ers’ injured cornerstones. Into the spotlight trudged Purdy, the final pick in last year’s draft—Mr. Quite Relevant right now. The Niners won 10 straight, netting the NFC’s No. 2 playoff seed, which sent the NFL’s hottest team careening, it seemed, back to the game they lost to Kansas City three years ago.

Would a defense so stingy it still clips coupons, an offense loaded with talent but missing the most important part, and a coaching wizard amid perhaps his greatest masterpiece lead back to the Super Bowl? Would Kyle Shanahan add a fourth Lombardi Trophy to his family’s trophy case, returning San Francisco to its rightful perch?

It sure seemed that way, right up until the meteorologists began forecasting a storm that threatened to make Saturday’s game wet, windy and, most importantly, unpredictable. Reports suggested that rain would fall in sheets, and winds would pick up and transport small children down the block. Signs on the U.S. 101 highway cautioned drivers to brace for “extreme weather.” The state’s governor, Gavin Newsom, declared a state of emergency earlier in the week. Parks closed, electricity went out and 45-foot waves reportedly gathered nearby in the Pacific Ocean.

Shanahan described the expected conditions as a “distraction test.” He attempted to deliver an upbeat sell: no lightning, it’s football and all the rest. But he also admitted that, deep into the stormiest of seasons, the weather was starting to, if not fray, then at least test his nerves.

The storm wasn’t all that concerned him. The hottest team in football had wrapped up the NFC West title more than three weeks ago; for Shanahan and his staff, the balancing act was being careful with some players, but not so careful as to diminish their chance to obtain the highest-possible seed. That meant answering questions about his playoff record—4–2 before Saturday—as a head coach. While the mark itself wasn’t bad at all, the offense’s performance in those games could be generously described as modest: 21.7 points per game and the four total touchdown passes, compared to six interceptions, thrown by his quarterbacks. Purdy had been a revelation, but the sample size was small. Pete Carroll, meanwhile, held an 8–4 record over Shanahan since 2017.

So, yes, the oddsmakers made San Francisco a 9.5-point betting favorite. Yes, Shanahan welcomed Deebo Samuel back to an offense that had excelled in his absence. Elijah Mitchell returned, too. But it could feel, as the game drew closer, as if the Seahawks had a chance to pull off a seismic upset; fate and circumstances and history had at least delivered better odds. The clouds had aligned, the thinking went, in favor of Seattle.

Rain pounded the turf at Levi’s Stadium early Saturday morning. But the storm soon gave way to weather conditions that made the dire forecast look comically overblown in hindsight. An hour before kickoff, rain spit and stopped; the sun even took an occasional peek through the clouds and fog. It was 60 degrees outside, and the tailgaters showed up in full force. They carried ponchos and wore layers of clothing and bumped California classics in the parking lot, bouncing and drinking to Dre and Snoop and N.W.A.

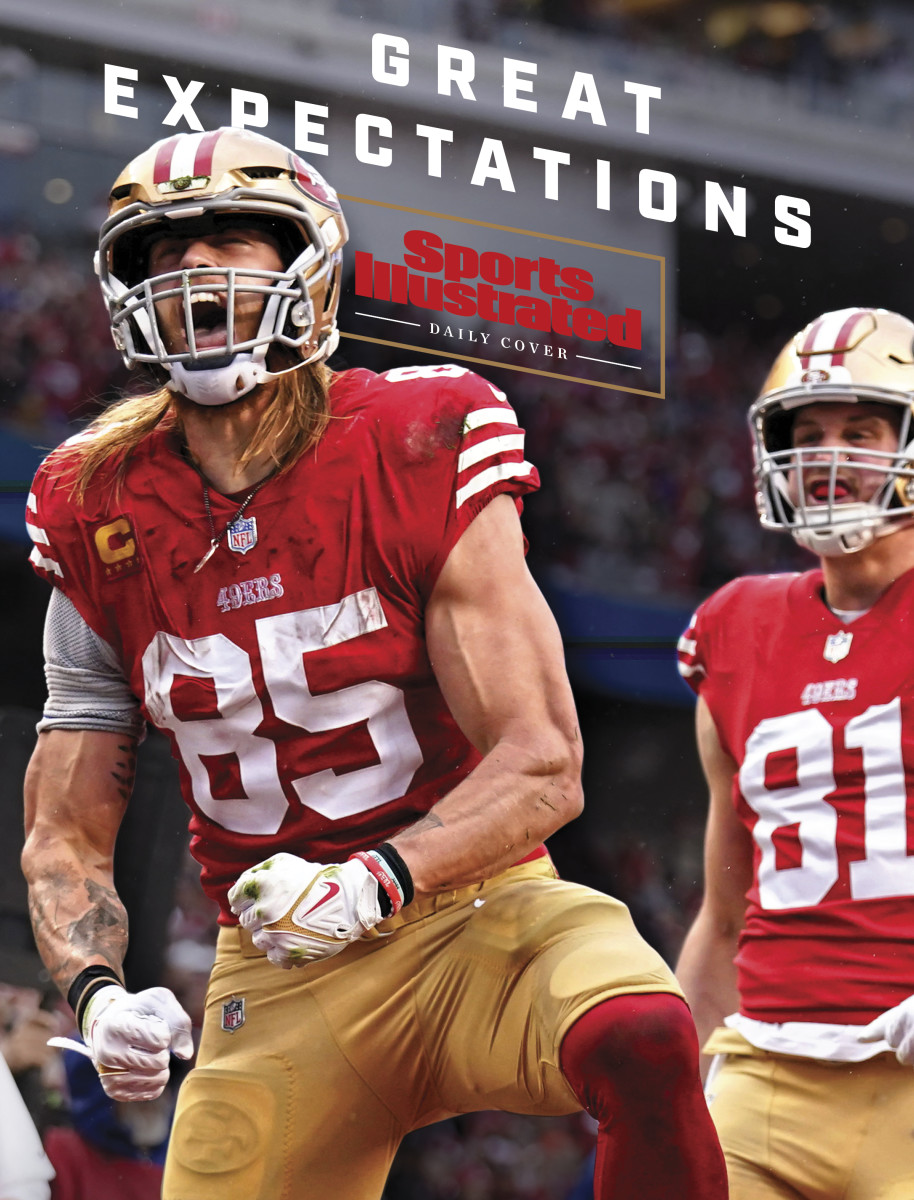

Savvy entrepreneurs hawked umbrellas and knit caps while surrounded by fans clad in jerseys that announced the Niners’ history, from Montana and Rice to Young and Patrick Willis and many more. But the Faithful wore jerseys for current players, too: Samuel, George Kittle, Brandon Aiyuk, Fred Warner, Nick Bosa and the rest. And no combination was more indicative of the 49ers’ season than the number of QB jerseys. Some donned Lance’s No. 5; others, Garoppolo’s 10; still others, Purdy’s lucky 13.

Inside the stadium, employees handed out red towels, just in case. The crowd arrived late, perhaps in anticipation of a deluge. They would get one, just not the kind the meteorologists predicted. No, this monsoon was the 49ers themselves, from the defense led by three first-team All-Pros (Bosa, Warner, Talanoa Hufanga) to the first rookie quarterback to orchestrate a playoff win since Russell Wilson in 2012.

The rain wasn’t a deterrent for fans ready for the start of a Super Bowl run.

Cary Edmondson/USA TODAY Sports

Television cameras captured Purdy walking into the stadium. He wore a white windbreaker. His eyes were downcast. He swung a water bottle with his right arm. He looked like a baby-faced teacher heading into a middle school math class he’ll never control. But as the game kicked off and San Francisco took control, that impression hardly mattered.

Instead, there was Arik Armstead wrecking the Seahawks’ first drive with a third-down sack. There was Aiyuk, settling into an opening in Seattle’s zone coverage, for a 19-yard completion. There was Samuel, back and apparently healthy, rumbling off left tackle for 22 yards. And there was McCaffrey, sailing up the left sideline for 68 yards and catching a touchdown pass for a 10–0 lead.

The reigning NFC player of the month—after a six-week stretch to close the regular season with 27 receptions, 767 yards from scrimmage and seven touchdowns—McCaffrey again displayed how he changed the 49ers’ offense. Shanahan recently told the team’s radio network that McCaffrey reminded him of Julio Jones, who Shanahan coached as the offensive coordinator in Atlanta, in how his presence and skill set moved defensive players around and to places they weren’t comfortable going. Both players freed up Shanahan’s innovative mind to add layers to his schemes, leading to confusion, contempt and, ultimately, touchdowns.

McCaffrey helped free Kittle. He helped the 49ers run the ball, even when he himself did not carry it. He served as a willing decoy when necessary, while subbing in for Samuel after knee and ankle injuries sidelined him starting in Week 14. Getting beat was the only beat the 49ers missed from that point on. The four draft picks necessary to acquire McCaffrey in mid-October began to seem more and more like a bargain. Or a heist.

McCaffrey was fully integrated into the lineup for the final 10 regular-season games. San Francisco won them all, while the offense averaged 30.5 points. Compare that output and those results to the first seven contests this season, when S.F. lost more than it won and the offense averaged 20.7 points. No wonder Carroll called the Niners “loaded and healthy and on a roll and about as hot as you could possibly get” last week.

On Saturday, in the first quarter alone, the Seahawks ran 16 plays, and the 49ers ran 11. But the 49ers gained 133 yards, while the Seahawks gained only 62. San Francisco averaged 18.6 yards per rush in that stretch while displaying the versatility that makes the Niners so dangerous. They’re a complete team that can win games in myriad ways. This quarter proved that. It demanded that anyone still doubting San Francisco should shift the 49ers toward the top of any list of Super Bowl contenders. It showed opponents the conundrum that’s in play here. How to stop McCaffrey and Samuel and Aiyuk and Kittle and, even if all that happens, still score on DeMeco Ryans’s defense. It didn’t seem possible. At least until it did.

Forty-five minutes after the game ended, Purdy climbed the stairs to the stage in the interview room and answered questions with his hands in his pockets, swaying gently back and forth. He projected calm and confidence in something close to a monotone. He copped to the pregame nerves that swirled in his stomach. He could have passed for a high school senior. Instead, he had passed for 332 yards and three touchdowns, and, if not for a late Aiyuk drop in the end zone, he would have thrown another.

In response to a question about his “slithery” footwork, Purdy gave a thoughtful answer that could have been whittled to something more like this isn’t my first game. Yes, he knew how to scramble, always had. Yes, he could freelance and make plays. “It’s something I’ve always done my whole life,” he said, “in terms of finding a way.”

Tom Gormely, cofounder of Tork Sports Performance and one of Purdy’s private coaches, saw that firsthand all spring. While training Purdy for the draft, Gormely and the private quarterbacks coach Will Hewlett certainly helped Purdy fix and improve some biomechanical flaws. But that’s not what stood out to them about him.

What stood out was Purdy’s focus, attention to detail and confidence. He asked a million questions. He wanted to be coached. The last pick in the NFL draft didn’t see himself that way; he possessed a swagger. “If people watched him in college [at Iowa State], he turned around that program,” Gormely said Friday. “Like, he’s a playmaker. He’s a gamer. He’s going to make plays.”

Gormely found Purdy to be “super confident, super fun, loving, super laid-back, super friendly.” Purdy possessed an odd combination of traits this way. His strength was a combination of self-awareness, self-deprecation and self-confidence. He could partake in Mr. Irrelevant events and believe he could start in the NFL.

What made Purdy an unusual prospect—no cannon of an arm, acutely aware of his own limitations, creative, smart, always prepared—made him perfect for Shanahan. He replaced the injured Garoppolo and played out of his mind. Purdy was steady. Purdy was sharp. And Purdy was surrounded by elite skill players, a strong offensive line and Shanahan.

The combination of those factors led to results no one saw coming. Late Saturday, Warner stood behind the same lectern and admitted that when Garoppolo went down against Miami, the 49ers stole glances at one another, wondering what might happen to their season. In came Purdy, in Week 13, against a playoff team coached by McDaniel, perhaps Shanahan’s most brilliant disciple. Purdy won that game and the next one (Tampa Bay) and the next four after that (Seattle, Washington, Las Vegas, Arizona). He became the fourth quarterback since 1950 to win his first four starts. He won his fifth. He won a division title. The No. 2 seed. “That’s him,” Gormely says. The surprise being that people have been, well, surprised.

“He showed us over and over again who he is,” Warner said late Saturday.

Shanahan seems to trust Purdy implicitly, despite age and experience and other reasons that signal such trust might not be the best idea. Ahead, 21–0 against the Bucs, on the 49ers’ final possession of the half, most coaches would have played it safe, run the ball and sprinted toward the locker room. With a rookie quarterback making his first start, Shanahan called five straight pass plays on the drive. Purdy found Aiyuk for a touchdown and a 28–0 lead. Purdy had earned that trust, his coach said, by “letting it rip” at times, being “smart with the ball” at others and beating the Seahawks back in December while grimacing through a rib injury.

If he’s a dreaded and mislabeled system quarterback, Purdy is also a quarterback who has improved a lauded-consistent-and-established system. He nabbed the most recent offensive rookie of the month honors. He drew praise for his poise. But just when everything seemed about perfect Saturday, the deepest fears of every 49ers fan began to materialize.

Purdy was late—very late—on an open touchdown throw for Jauan Jennings, a four-point mistake. The 49ers continued to move the ball in the second quarter, but all those yards netted more field goals than touchdowns. Meanwhile, the Seahawks did their own storming, right back into the game, where they took leads of 14–13 and 17–16. The latter resulted from defensive back Jimmie Ward’s barreling into Seahawks quarterback Geno Smith with one second left before halftime. The penalty pushed Seattle into field goal range, and Jason Myers sailed this kick through the uprights from 56 yards out.

It all added up to doom, potentially. Was this the moment the magic ended?

At halftime, San Francisco didn’t look to Shanahan exclusively. Nor did a single voice begin to speak. Instead, several coaches and more than a few players gave voice to perhaps the most absurd half in a strange season.

Bosa later admitted feeling “a little nervous.” Charvarius Ward said Ryans made “some” halftime adjustments. Linebacker Dre Greenlaw said Ryans didn’t make any changes, instead telling his charges to up their intensity and focus for the second half. “We know we’re a lot better than that,” Greenlaw said afterward.

Shanahan also spoke directly to Purdy. “The plays are there,” Purdy said his coach told him. “The opportunities are there. We just gotta keep it simple and get it to the guys.”

As if they had spoken reality into existence, the 49ers did exactly as they told one another they would; slowly at first, then all at once. Purdy drove them down the field after halftime, with an assist from the Seahawks’ defense, when safety Johnathan Abram tackled Samuel and grabbed one of Samuel’s legs as he climbed up, sparking pushing and shoving and a scrum. Purdy soon sneaked into the end zone to reclaim the lead.

Still, Smith proved that his remarkably resurgent season in Seattle was no fluke. He drove the Seahawks right back down the field, right until the 49ers’ defensive line collapsed his pocket, swarming as several defenders closed in, and Charles Omenihu knocked the ball loose and Bosa pounced on it like a forever-dangerous large cat.

This was the 49ers’ season, in miniature. Lose running back Elijah Mitchell, then left tackle Trent Williams and nose tackle Javon Kinlaw, then Armstead, Emmanuel Moseley, then Bosa. Lose games. Lose everything but faith. Return some players but not all. Continue fighting, continue forward. Figure it out. Change quarterbacks. Change quarterbacks again. Fall behind against the Chargers (Week 10) in prime time and roar back. Thump the Cardinals in Mexico City (Week 11). Narrowly avoid an upset by shutting out the Saints. Unleash McCaffrey a little more each week. This is how San Francisco beat the Seahawks and how it became the NFL’s hottest team.

Along the way, because of everything, San Francisco started to play at an elite level. Ryans’s defense was the tentpole; Shanahan’s offense, under Purdy, without Samuel, the best kind of surprise. All worked in concert throughout the fourth quarter Saturday, despite the weather, which wasn’t all that bad. Purdy led another touchdown drive, found Kittle for a two-point conversion and opened up a 31–17 advantage. He would later say that the offense didn’t overthink its plan, that it finished drives, stalling no more.

By the time Mitchell scored in the fourth quarter, giving the game and this season the symmetry both deserved, Purdy even broke from his stoic demeanor. He said it happened because of the play itself, which had broken down. He was supposed to start on the left side of the field, hoping to find an open Aiyuk, then go through his progression. He did all that but couldn’t find an open receiver. With ample time and not an ounce of panic, he knew, even in that moment, that Mitchell was supposed to give up on his blocking and leak into the right flat. Mitchell did both. He was so open he could have held a tea party and still scored. Purdy thumped his chest with both fists, then later called the sequence “a big moment for all of us.”

The defense resumed its dominance, which had ranked first in points allowed throughout the season and led the NFL with 20 interceptions. Turnovers became its trademark, which marked a pivotal improvement compared to 2021, when the Niners ranked 19th in taking the ball away and 26th in interceptions snagged.

The defense even responded to a challenge from Shanahan before the Washington game in Week 16. The unit had responded by forcing two turnovers on downs, while Bosa set a new personal career high in sacks (he finished the season with 18.5). Greenlaw morphed into Big Play Dre. Warner stated a strong case for himself as the league’s best linebacker. The defense overall didn’t present a single obvious weakness while transforming that turnover weakness into its greatest strength. Players pointed to weekly meetings dedicated to that specific emphasis, nothing more. They pointed to a coach (Nick Sorensen) who morphed into a turnover guru of sorts.

It all spoke to the same thing: a gathering storm that had not a single cloud. Shanahan bolstered his coach of the year candidacy. Purdy entered the offensive rookie of the year conversation, despite his lack of snaps. The hottest team in football sped into the postseason, then overcame a bad half that wasn’t all that terrible, then turned on the turbo and took a team that perpetually gives them problems and showed the Seahawks just how wide a gap they have opened.

Maybe half an hour after the game ended, Shanahan’s friends and family headed toward the exits, through the bowels of the stadium. His father, Mike, owner of three Super Bowl rings (two as a head coach in Denver, another from his time as a 49ers assistant), carried a notebook in his left hand. Theirs is a football family, a coaching family. Before hitting the swarm of reporters waiting to speak to his son’s now formidable team, he banked right, toward the exits, tan and unsmiling, knowing that bigger tests await and soon.

He also knew that his son’s team has formed the kind of riddle that makes San Francisco the toughest kind of postseason out. With all those weapons, the Niners can run the ball (eighth in the NFL), pass the ball (when Purdy lets it rip) and protect the ball (hence the turnover margin). They have a do-it-all utility man in fullback Kyle Juszczyk, the most athletic offensive lineman in pro football in Trent Williams and, now, a rookie signal-caller who’s 1–0 in the playoffs, the win coming in his seventh NFL start.

Mike Shanahan knew that, in the regular season, 15 of the Niners’ first 16 opponents all lost their next game after playing San Francisco (the lone exception was the Chiefs, who had a bye week before resuming play). Perhaps this meant nothing. But it’s also possible that the 49ers’ style—physical and imposing, balanced and explosive—had taken tolls in the physical and mental senses.

Add everything up, and there’s little reason to think San Francisco will not at least challenge Philadelphia for the NFC’s berth in Super Bowl LVII. Perhaps the 49ers should be considered the conference favorite, at this point. Just ask Harry Edwards, the activist, professor and longtime team consultant. In an email, Edwards noted that his 49ers tenure began in 1985. He compared owner Jed York, Shanahan and his staff and general manager John Lynch to their counterparts from the glory days (Eddie DeBartolo; Bill Wash and his staff; and John McVay, respectively).

Both groups, he wrote, embodied the culture Walsh is famous for, “an optimum mix of RESPECT (in terms of coaching technical proficiency), AFFECTION (players want THEIR position coach, coordinator, and head guy to be the staff leaving the field with their heads up), and AUTHORITY (players and coaches alike TRUST, BELIEVE IN, AND BUY 100% INTO A VISION of how the team and organization must function to be successful).” Executive command, Walsh called this. It started from the top and bled down, until everyone committed and cared about and pushed one another. Walsh, Edwards wrote, tabbed that organizational ethos as the “greatest single characteristic” of the dynasty he created.

“I see more of ALL of this in THIS team and in the 49ers’ building now than at any time since the BILL WALSH AND THE TEAM OF THE ‘80’s,” Edwards wrote.

So, no, the 49ers did not celebrate Saturday. They shrugged off the weather. They lauded their rookie quarterback. (“He’s a special dude, bro,” Greenlaw said.) They thanked their defense. But they also knew that the men Edwards compared their decision-makers to put those years on that banner hanging in their locker room. And, sure, Saturday did matter. But only in so much as their victory marked another step in adding to the banner they see every day they come to work.