This story was originally published on April 11, 2022. It was included in a year-end list of SI’s best stories of 2022.

Competitive sports are built on the concept of fair play, which helps explain why so many oppressive regimes see value in games. Any form of good, wholesome fun can seem like it is presented by good, wholesome people, even when the facts say otherwise.

China, with its appalling human rights record and opposition to an independent Taiwan, hosted the recent Winter Olympics with the strategically peaceful slogan Together for a Shared Future. One of the stars of those Games was Eileen Gu, a California-born skier who chose to compete for her mother’s homeland of China, implicitly embracing the government of China rather than the U.S., whether or not that was her intent. Gu declined to say whether she renounced her U.S. citizenship to gain a Chinese passport, as Chinese law requires, but she did gush about “the ability of sport to bridge the gap and to be a force for unity.”

That was music to the ears of the Chinese government—and to those of the Saudi government, as well. Saudi Arabia has long attempted to lure star golfers to events there with large financial guarantees, using the players and sports to present a benign image of the country. And they’ve succeeded: Two-time Masters champion Bubba Watson recently praised their efforts to support women’s golf, completely ignoring the fact that, until last summer, women needed permission from a male guardian to live alone.

The Saudis, to use Phil Mickelson’s words, are “scary motherf—— to get involved with,” yet he is involved anyway. Mickelson has spearheaded the Saudi-funded effort to create a world golf tour for the game’s elite—a much larger effort to cleanse the country’s image.

Most disturbing is that Mickelson knows exactly why and how he is being used.

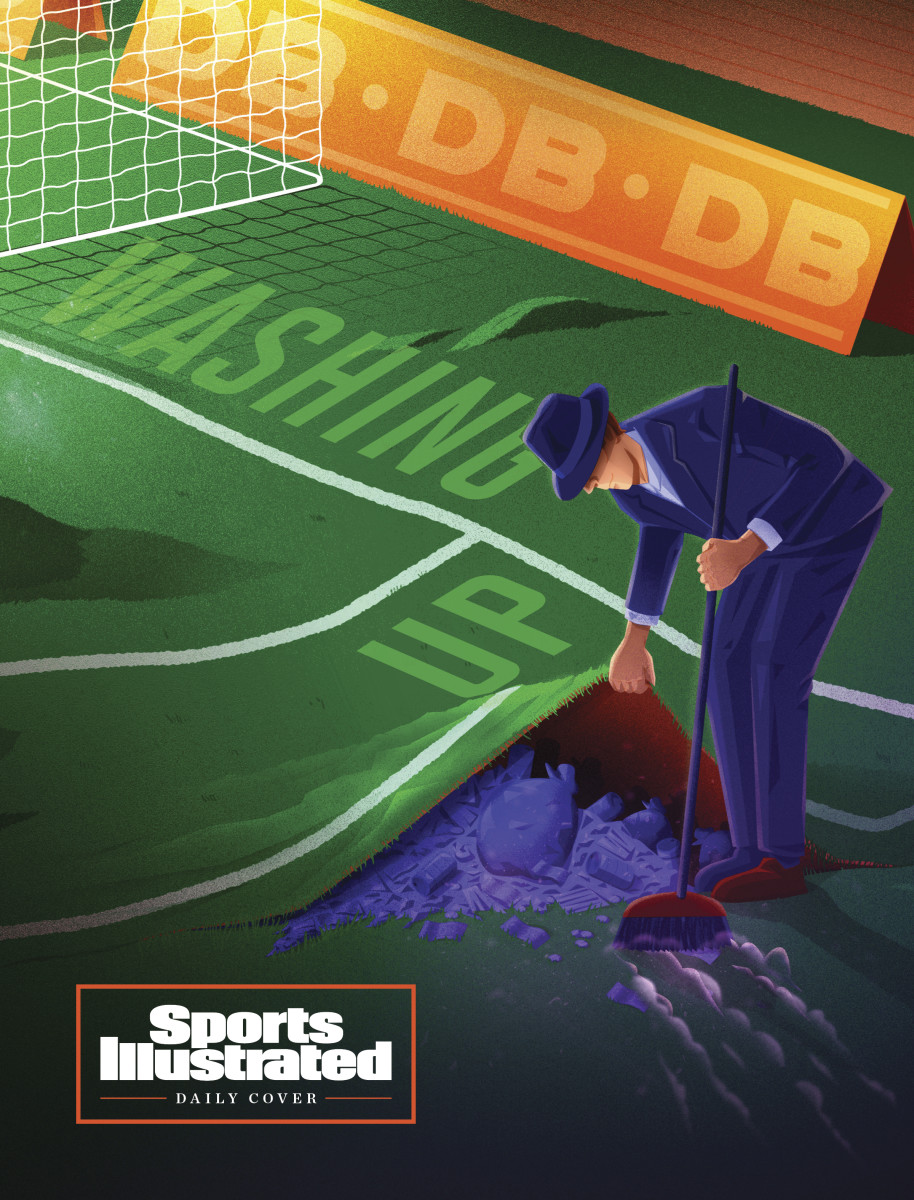

“Sportswashing,” Mickelson called it in an interview with writer Alan Shipnuck of The Firepit Collective for Shipnuck’s upcoming book, Phil: The Rip-Roaring (and Unauthorized!) Biography of Golf’s Most Colorful Superstar.

Sportswashing is the use of sports to present a sanitized, friendlier version of a political regime or operation. Mickelson later apologized for using words that do not reflect his “true feelings,” but that apology was just another form of sportswashing; he should think the people funding the new tour are scary bleeps, because they are. They are determined to succeed, too: They just announced a 2022 schedule that includes four events in the U.S.

Listen to an audio version of this story on our podcast, Sports Illustrated Weekly.

The term sportswashing is relatively new, but the practice is almost as old as sports. Paul Christesen, a professor of ancient Greek history at Dartmouth, says it goes all the way back to the original Olympics.

Christesen tells this story: “There’s a long war between Athens and Sparta. Athens looks like it’s getting its ass handed to it. They’re getting the crap beaten out of them. And everyone thinks that they’re down and out. And so an Athenian politician named Alcibiades comes to the Olympic Games in 416 [B.C.E.], right in the middle of the war, when things are going bad for Athens. And he enters several chariot teams into the four-horse chariot race and wins first, second and either third or fourth place. And that’s like an F1 racing team—it was insanely expensive.

Qatar has let nothing stand in the way of stadium construction for the 2022 Cup.

Matthew Ashton/AMA/Getty Images

“And they all said to him at home, ‘You’re crazy. We don’t have those kinds of resources.’ And he’s like, ‘Listen. Everyone thought we were down and out. I win all these events at Olympia, and now everyone in the Greek world thinks that we’re just fine. And they’re terrified of us.’ It was a straight-up geopolitical maneuver.”

Modern sportswashing can take many forms. Qatar wants the world to see it as the host of the 2022 men’s World Cup, not a country where migrant workers are exploited. (Including for the competition: Thousands of workers have died over the last decade building the World Cup infrastructure.) Former Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Tse-tung once banned golf, calling it a “sport for millionaires,” but the game has since become both legal and popular in China, leading to propaganda that golf was actually invented there. If you were to listen to the Party, you’d believe that everything that happens in China started in China and belongs to China.

Competing for China, Gu was the first freestyle skier to win three medals at one Games.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

If you think that kind of silly nationalistic fable would never fly in the U.S., I have two words for you: Abner Doubleday. Millions of American kids have grown up believing Doubleday invented baseball—a myth that was created a century ago to distance the national pastime from its foreign antecedents, cricket and rounders.

“It is a proven fact that the game now designated ‘Base ball’ is of modern and purely American origin,” insisted one of the game’s first power brokers, Albert G. Spalding, in his 1911 book America’s National Game.

There is a hint of sportswashing every time a U.S. president throws out a first pitch or a college president talks about football as the “front porch” of a university. Sports seem like they aren’t political, which is precisely why they are so often used for political purposes. The drama seduces us, and our passions distract us, and so we swallow whatever government officials feed us without even realizing it.

After Russia invaded Ukraine, the International Olympic Committee and FIFA moved to ban both Russia and its ally Belarus from competition. That might not seem like much of a penalty for Russia’s atrocities in Ukraine, but don’t think of it as a punishment. Think of it as taking away a weapon. President Vladimir Putin has long used sports to shape Russia’s image as both powerful and reasonable.

Shortly after delivering a famously blistering anti-West speech in Munich in 2007, Putin successfully lobbied the IOC to award the ’14 Winter Olympics to Sochi, a one-two punch that made Russia seem like it (and its leader’s views) belonged on the world stage. Russia kept using sports to look strong (instituting a state-sponsored doping program to increase the country’s medal count) and friendly (Putin opened the ’18 men’s World Cup by welcoming spectators and journalists to “open, hospitable, friendly Russia.”) Earlier this year, he attended the ’22 Winter Olympics opening ceremony and appeared to fake falling asleep as the Ukrainian delegation entered the stadium, then invaded Ukraine shortly after the Games ended.

The modern Olympics, like the ancient ones, have often been a political tool. When Nazi Germany hosted the 1936 Summer Olympics, it saw the event as a pep rally for the Aryan race. The Games’ slogan was “I Call the Youth of the World!” Adolf Hitler built the Olympiastadion in Berlin, which supposedly seated 100,000 people, and the Nazis paid for propagandist filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl to make a documentary about the Olympics. The Nazis also took down signs banning Jews from public places, in an effort to seem . . . well, open, hospitable and friendly.

“People take sports super seriously,” Christesen says. “And as soon as people do that, you can leverage it for geopolitical purposes. My students are like, ‘Everyone’s too cynical [for it to work now]. Of course it works. It always works. In some ways, it works better now, because you’re so bombarded by it all the time that you can’t escape from it.”

A PR tactic that has been successful for more than 2,000 years is probably not going away anytime soon. But sports fans and journalists can at least call sportswashing what it is, and athletes should show some self-respect when tyrants come calling. There are plenty of ways to host games without being part of such a dirty one.

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here:

• Sportswashing and Global Football’s Immense Power

• Rory McIlroy Was Once the Next Tiger Woods. So, What Is He Now?

• We Haven’t Seen the Best of Shohei Ohtani