Good morning, I’m Dan Gartland. Well, that’s one way to even a series.

In today’s SI:AM:

⚾ Cristian Javier’s unhittable fastball

🏈 Strength vs. strength in the SEC

🤑 Dan Snyder takes the first step toward selling

If you’re reading this on SI.com, you can sign up to get this free newsletter in your inbox each weekday at SI.com/newsletters.

You can’t win if you can’t get a hit

Unlike the night before against Lance McCullers Jr., the Phillies couldn’t figure out Astros starter Cristian Javier in Game 4. At all.

Javier and three relievers (Bryan Abreu, Rafael Montero and Ryan Pressly) combined to throw just the second no-hitter in World Series history. Meanwhile, Houston’s hitters touched up Aaron Nola and José Alvarado for five runs in the fifth inning on their way to a 5–0 victory.

I can’t get terribly excited about combined no-hitters but Javier’s start is still one of the best I’ve seen in the postseason. Over six innings of work, he struck out nine and walked two. Only nine balls were put in play and of those, just two had an expected batting average (according to Statcast) of higher than .090. In other words, Javier was untouchable and even when guys did make contact, it was extraordinarily weak. What makes that even more unbelievable, as Tom Verducci explains, is that Javier did it by throwing predominantly fastballs—and not even particularly hard ones:

Of his 97 pitches, Javier threw 70 four-seam fastballs, a remarkable 72% daily dose of heat. Since 2008, when pitch tracking began, nobody had ever thrown that many four-seamers in a World Series game. The previous high was 68 by John Lackey in Game 6 of the ‘13 Series.

Javier averaged 93.4 miles per hour on his heater, slightly below the major league average (93.9) and below his yearly average (93.8). Still, the Phillies tried swatting 41 times at those 70 fastballs, with all the success of trying to catch a gnat in midair with your hand. They whiffed six times, made an out eight times, and ticked off 27 foul balls, most of them straight back and well into the air as they kept nicking the bottom of his fastball. The ball simply was not in the area they tracked it—just a few inches higher because of the gravity-fighting, Matrix-like qualities of that strange heater.

Javier doesn’t throw particularly hard, but it’s the deception of his fastball that makes him so dangerous. Here’s Verducci again:

Every fastball drops. Pitchers throw from an average of about six feet off the ground (Javier actually has a low release point, 5.65 feet, which aids his deception) and the ball crosses the plate at about three feet off the ground near the top of the zone. But because of how the baseball comes out of his hand—his spin is good, but not elite—his fastball doesn’t drop as much as the average fastball of the same velocity. His fastball is three inches higher than where it should be, based on the average fastball. Only the fastball of Nestor Cortes of the Yankees has a greater gap between perception and reality (3.2 inches).

Against McCullers in Game 3, the Phillies knew what was coming. They knew what was coming last night, too. They just couldn’t wrap their heads around it.

It’s a shame Javier’s pitch count got up too high for him to pursue the complete-game no-hitter but the Astros didn’t need him to go any deeper into the game. They turned to their excellent bullpen, which continued to shut down the Philadelphia bats.

The good news for the Phillies is that the series is tied 2–2. Game 5 is tonight, with Noah Syndergaard facing Justin Verlander. The Phillies were able to get to Verlander in Game 1 but it would be a surprise to see the likely AL Cy Young winner struggle again. Can the Phillies’ bats wake up or will the Astros be headed back to Houston with a chance to close out the series?

The best of Sports Illustrated

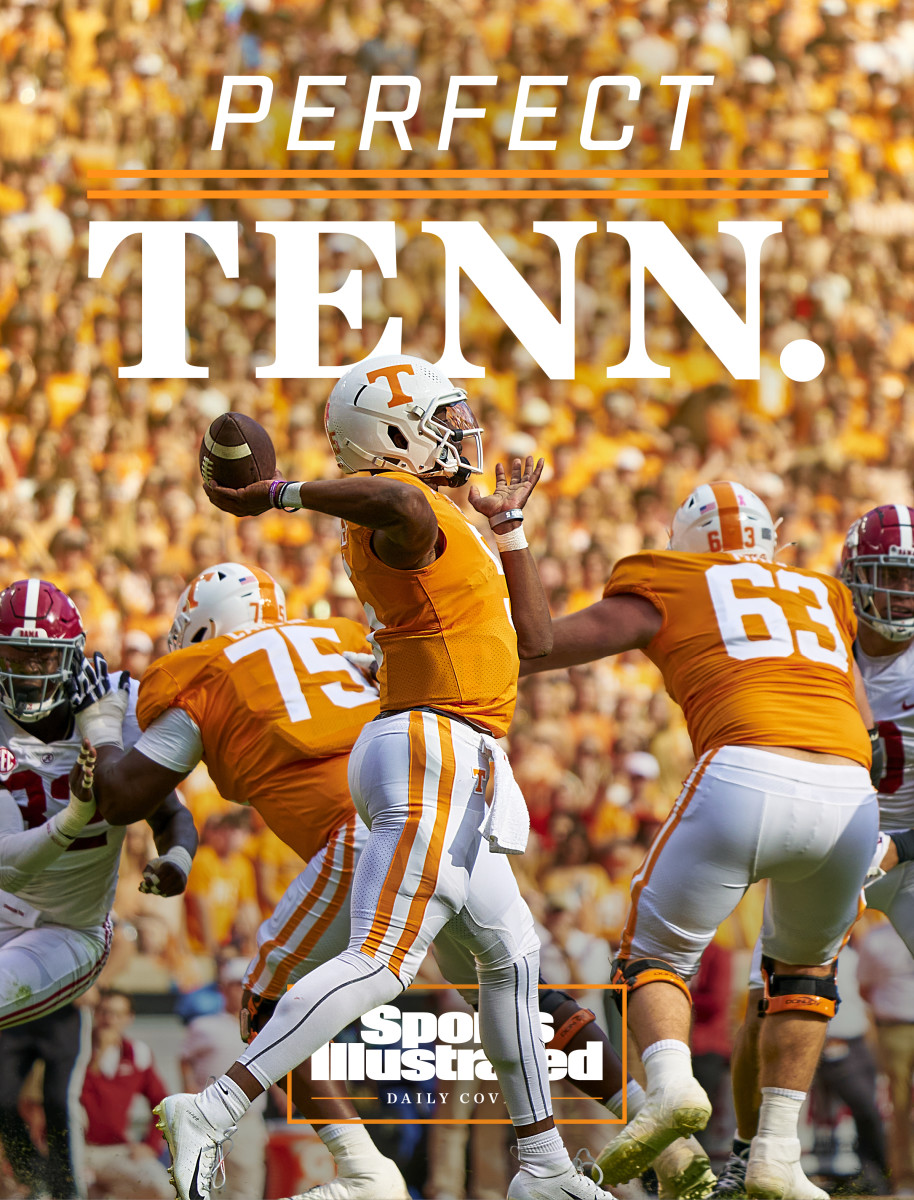

In today’s Daily Cover, Pat Forde previews the monumental showdown between Tennessee and Georgia this weekend:

Six Vols receivers have caught passes longer than 50 yards. Forget Ohio State; Tennessee is the national leader in explosive pass plays. Through eight games, the Vols have 30 passes of 30 yards or longer, seven more than the national runner-up. (One out of every six Tennessee completions is a 30-plus yarder.) And they have 19 passes of 40 yards or longer, six clear of second place, an average of 2.38 per game. Since 2010, seven FBS teams have averaged two or more 40-plus-yard pass plays per game—but none as high as Tennessee’s current average.

Stephanie Apstein looks at the role backup catcher Christian Vázquez played in the Astros’ no-hitter. … Albert Breer has a detailed analysis of Dan Snyder’s decision to explore a sale of the Commanders, including how much the franchise could sell for and who might want to buy it. … Conor Orr argues that the NFL should look at more than the wealth of a prospective owner when approving a potential sale of the Commanders. … Kevin Sweeney ranked all 363 teams in Division I men’s basketball. … Chris Mannix explains why Russell Westbrook has what it takes to be a great sixth man. … Super Bowl ticket reservation prices for the Seahawks rose another 106% following Seattle’s third straight win.

Around the sports world

Kyrie Irving released a statement about spreading antisemitism but did not apologize. … Browns GM Andrew Berry said he expects Deshaun Watson to start the first game he’s eligible to. … This is an interesting article about the Bonneville salt flats, the popular destination for land speed record attempts, which is in danger of disappearing. … This excerpt from Timothy Bella’s new biography of Charles Barkley details a story I didn’t know about: the persistent ’90s rumor that Chuck was dating Madonna. … Gonzaga is reportedly interested in joining the Big 12. That road trip to UCF would be a tough one. … ESPN has hired Aces coach Becky Hammon as an NBA analyst.

The top five…

… things I saw last night:

5. Lamar Jackson’s reaction to getting called out by Chris Jericho at AEW Dynamite.

4. Tyler Herro’s game-winner against the Kings.

3. Central Michigan’s jump-pass fake field goal.

2. Kyle Schwarber’s thoughts on being part of history.

1. Matt Ryan’s game-tying three for the Lakers and his reaction to all the reporters crowding around his locker: “I feel like LeBron.”

SIQ

On this day in 2013, two months after Peyton Manning accomplished the feat, which quarterback became the seventh player in NFL history to pass for a record seven touchdowns in a game?

- Philip Rivers

- Matthew Stafford

- Tony Romo

- Nick Foles

Yesterday’s SIQ: On Nov. 2, 1990, the Suns and Jazz opened their seasons by playing the first regular-season games outside North America for any major U.S. sports league. Where did they play?

- London

- Paris

- Beijing

- Tokyo

Answer: Tokyo. They played two games, with Phoenix winning the first and Utah taking the second.

The biggest challenge for the teams was overcoming the jet lag associated with traveling to the other side of the world. Suns coach Cotton Fitzsimmons, Jack McCallum wrote in SI at the time, tried to get his players used to the time difference by holding two practices back in Phoenix at 3 a.m. before the team flew to Tokyo. The Jazz had a harder time. They closed out the preseason with games in Toronto and Providence before traveling to New York to catch a commercial flight to Tokyo. Utah coach Jerry Sloan had a questionable strategy for getting his guys acclimated, McCallum wrote:

Sloan’s theory on fighting fatigue and jet lag had his players working out as soon as they arrived in Tokyo. He said at a press conference last week that athletes “need to get out and work a little” after a tiring trip, at which point his two superstars, [Karl] Malone and [John] Stockton, who were sitting nearby, rolled their eyes.

By all accounts, though, the games were pretty good. Malone scored a combined 62 points, including two clutch free throws in the final minute of Utah’s one-point win in the second game. And everyone involved was glad that the teams split the two games. “The regular-season schedule is tough enough and long enough without having one team start at 0–2 three quarters of the way across the Pacific Ocean,” McCallum wrote.

From the Vault: Nov. 3, 1986

Thanks to the Mets’ miraculous comeback in the bottom of the 10th inning (aided by Bill Buckner’s infamous error at first base), Game 6 of the 1986 World Series is one of the most famous games in baseball history. You’ve seen that clip of the ball going through Buckner’s legs and Ray Knight jumping for joy as he heads home a million times. Unless you’re a big baseball fan, maybe you haven’t heard the great behind-the-scenes story of the quickly scuttled celebration in the Boston clubhouse. Here’s how Ron Fimrite relayed it in that week’s issue of SI:

The suddenness of the Red Sox’ demise in Game 6, and their proximity to the Promised Land, might best be illustrated by what happened to NBC broadcaster Bob Costas and his crew in the bottom of the 10th. Costas was perched in the corner of the visiting dugout nearest to the runway leading to the clubhouse. It was past midnight, of course, because with the television-induced late starts, this had become the Witching Hour Series. Costas had taken up his position in anticipation of the historic Red Sox victory. The rest of his crew was already inside the clubhouse, busily setting up the interview platform, positioning the cameras and aiming the lighting. They were ready for the big moment.

When [Wally] Backman flied out meekly to open the 10th, Costas edged toward the tunnel. Then when Hernandez lined out, Costas headed for the clubhouse, mentally preparing himself for the champagne-soaked interviews that would follow within minutes. Inside the locker room, Costas learned that he would be flanked on the platform by Red Sox president Jean Yawkey and chief executive officer Haywood Sullivan, both of whom were waiting in the wings. Baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth would be there to present the World Series trophy to them and to read a congratulatory message from President Reagan. Costas was told that [Bruce] Hurst, winner of two Series games, would be given the Most Valuable Player award. The cellophane was draped over the players’ cubicles to protect their belongings from the spray of champagne. Costas decided to check the NBC monitor. Hmmm, [Gary] Carter was on first base. The game hadn’t ended. Then [Kevin] Mitchell got a hit, and Knight another. The game was far from over. Dave Alworth, the commissioner’s liaison man for television, dashed nervously into the busy room. If the Mets tied the game, he told Costas and crew, they would have to clear out of there, bag and baggage, in a big hurry.

Then came the wild pitch to [Mookie] Wilson. “I swear,” said Costas, “that ball had not stopped rolling before the technicians had packed up and gotten out of there. I had never seen anyone move so fast. I stayed behind to watch the monitor. And when that ground ball rolled between Buckner’s legs, they just pulled the plug on me and hustled me out of sight. We were all gone by the time the Red Sox, uttering what epithets you can imagine, got back there. It was amazing. It all happened so fast. We just disappeared.” And so did victory for the Red Sox.

Imagine how quickly Costas and the NBC crew had to clear out of the clubhouse. They must have been moving faster than even Knight.

Check out more of SI’s archives and historic images at vault.si.com.

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.