In a town in the south of the Brazilian province of Minas Gerais called Don Viçoso, there lived a young widow called Maria Rosalina. She had a baby son and loved him dearly, but he wouldn’t speak. Even when he was 2 years old, he had still not said a word. So Maria Rosalina called together the local benzedeiras, local women who performed rituals on moonlit nights. They gathered around the boy’s cot and intoned the traditional incantation: “Bili-bilu-teteia, Bili-bilu-teteia.”

The boy remained silent. So they tried again, and again. Finally, after several weeks of chanting on numerous moonlit nights, the boy called out: “Bilé.” And so that became his nickname.

Bilé adored football. He eventually became a goalkeeper and played for Vasco da São Lourenço. A local man would take his young son, only 3 or 4 years old, to watch training sessions. The boy, then known as Edson Arantes do Nascimento, liked playing in goal and whenever he made a save, he would call out his hero’s name. Except that he mangled the name, changing the B to a P: “Pilé, Pilé.” When the boy then moved to Bauru in the state of São Paulo, his Minas Gerais accent meant his teammates misheard his shout. And so was born the most famous nickname in football: Pelé.

Pelé, 82, died Thursday, after a monthlong hospital stay to regulate his cancer treatment. O Rei may have been Brazil’s king, but he was a gift to the world. And a branding agency couldn’t have come up with a better name. Pelé, the name, meant nothing and it meant everything. It’s a short word that begins explosively but soon becomes graceful. In English it sounds like both play and pearl. It’s the name of a deity in Hawai‘i. It sounds a lot like the Irish word for football–”peil”–or the Finnish word for game–”peli.” It meant something to everybody, and that collection of sounds was always something sporting and good.

The nickname defined him, to the extent that Pelé, after his playing career, became a walking brand. The great Brazilian forward Tostão has a theory that Brazilian players need nicknames because the clamor of Brazilian society means it’s essential for celebrities to separate public and private selves. In Pelé that distinction broke down. But that was later. First there was the footballer, and he was exceptional.

Pelé’s father, Dondinho, was a footballer who taught him how to play the game. Pelé practiced constantly with his friends, using a sock stuffed with rags, or occasionally a grapefruit, for a ball. His family was desperately poor. When Pelé was around 10, the mayor of Bauru held a tournament. Pelé and his club entered but were only allowed to compete when a local businessman provided them with boots. Pelé wasn’t used to playing anything other than barefoot, but his side got to the final, played at the stadium belonging to Bauru AC, for whom his father played. They won, Pelé was top scorer and for the first time he heard a crowd cheering his name.

He went on to win two São Paulo state junior championships with Bauru, where his coach was Waldemar de Brito, a great forward of the 30s and 40s. It was under Waldemar that Pelé became aware for the first time of “this extra vision that I seemed to have.” Waldemar knew what he had and when Pelé was 15 he took him to Santos, telling the club he was giving them the greatest player in the world. He was right.

Pelé made his debut at 15 on Sept. 7—the anniversary of Brazilian independence. Everything he did had a sense of greater significance, as though he were living out some great destiny. He scored his first goal in a 7–1 win over Corinthians de Santo André. At 16, he was the top scorer in Paulista championship and was called up to the Brazil national team for the first time. At 17, he won his first state championship and was named to the Brazil squad for the World Cup. This was a huge moment for him; one of his formative memories was of his father weeping as defeat to Uruguay cost Brazil the 1950 World Cup, and he was determined to ensure the tournament brought joy to Brazilians like his father.

He didn’t play in the first group game, or the second, but he was included in the third. Pelé scored for the first time in a World Cup in the quarterfinal, the only goal as Brazil beat Wales. He scored a hat trick in the semifinal as Brazil beat France 5–2, and got two more in the final as Brazil beat Sweden by the same score. He had won his first World Cup, as a 17-year-old, and he had finished as second top-scorer with six goals in four games. The world began to recognize the truth of Waldemar’s words. The 1958 final, Pelé said, was “the launch pad” for his career. Paris Match ran a story about him.

Pelé’s first goal in the final is one of his most famous. A ball is slung in from the left. He gets to it before Sigge Parling and then, as Bengt Gustavsson approaches, lifts it over his head, before volleying it low past the keeper. It’s a slightly odd goal, one that simultaneously requires strength and technical ability and yet is somehow obviously of its time. In the modern age, the second defender would have been much tighter to him. And there would have been another defender waiting as the ball looped over the head of the second: It goes high, drops slowly; modern players don’t have that much space. It is a slightly ungainly goal, because the ball falls too close to him and he has to dig it out of his stride. It doesn’t have the grace of, say, Paul Gascoigne’s similar goal against Scotland at Euro 1996.

Which matters only because footage of Pelé scoring is relatively rare. Who cares if a goal scored in a World Cup final isn’t quite as beautiful as it might be? And in its era, it was shocking: “Nobody had scored a goal like that before,” Pelé said. But what that goal and its celebration do is subtly add to a sense that Pelé was from a different era, that maybe he wasn’t quite all that, somebody removed from the modern game.

Actually, the opposite is true. Pelé was a modern footballer; he just happened to play in the past. He was almost laughably better than his contemporaries. He scored 58 goals in that 1958 Paulista season, a record that still stands. The records and trophies kept coming: 10 state championships, six Brazilian national championships, four Torneio Rio–São Paulo. But again, the mists of time intercede. What did these mean? How seriously was each one taken? Brazilian domestic competition has always been bewildering. Pelé skepticism is easy.

But look at the 1962 and ’63 Libertadores finals, both won by Santos. In ’62 they beat Peñarol after a playoff. They retained their title a year later with a 5–3 aggregate victory over Boca Juniors. Find the videos of those games and watch how good Pelé is. Watch, especially against Boca, how he will get the ball, drive forward with it, be kicked, have opponents hanging off him and somehow still find the right pass. He was not a physically big man, but he had remarkable explosive acceleration and strength, and a prodigious understanding of the distribution of players on the pitch. He had remarkable balance, something he put down to having trained in judo as a teenager.

Santos spent the 1960s touring the globe, playing friendlies to raise money. Pelé’s claim that he scored 1,283 goals is debatable—and, for a while, as Cristiano Ronaldo drew close to various of his landmarks, seemed infinitely expandable—but the issue of exactly what to include is not straightforward. Although many of his goals came in friendlies, they should not entirely be discounted; at least some of the games on those tours were of a very high standard indeed. Those games also enhanced the Pelé legend. A temporary ceasefire was supposed called in the Biafran War when he played in Nigeria. A crowd in Beirut tried to kidnap him to force him to play a friendly against Lebanon. He was feted everywhere he went, in Asia, in Africa, in Europe.

Alongside Muhammad Ali, although a far less controversial figure, he became the first truly global Black sporting celebrity. “I was fortunate to become wealthy and famous at a young age,” Pelé said, “and people treat you differently when you have money and celebrity.” In 1995, he was named Minister of Sport and so became the first Black Brazilian minister, a concrete example of the way he helped break down racial boundaries, even if he was aware how his status somehow thrust him into “a race apart—not Black or white but famous.”

Yet for all his on-field success, there was perhaps something missing. In 1962, Pelé had scored in Brazil’s first game at the World Cup, a 2–0 win over Mexico. But then he was injured in a 0–0 draw against Czechoslovakia and didn’t play again at the tournament. Brazil retained their title, but the star was Garrincha. Four years later, in England, Brazil was eliminated in the group stage, with Pelé the target of brutal tackling. Injured against Bulgaria, he missed the defeat to Hungary, and was then kicked out of the final group game against Portugal. As Brazil went out, an injured Pelé was helped slowly away, a blanket draped poignantly around his shoulders. Brave as he was, this wasn’t his world and, disillusioned, he retired from international football. He was 25.

Two years later, Pelé was persuaded back. He played in all six of Brazil’s qualifiers for the 1970 World Cup, scoring six goals as Brazil finished with a 100% record. But there was trouble before the finals. Brazil’s coach, João Saldanha, had been a baffling appointment. He had had a minor playing career with Botafogo, whom he had coached to the Carioca state championship in 1957. But he resigned a couple of years later and was working as a journalist when he was put in charge of the national side. That was strange enough, but he was also a committed leftist at a time when Brazil was run by the brutal military dictatorship of Emílio Médici.

The pressure seemed too much for him. He went chasing a critic with a gun and made a series of strange statements about a number of players, which included suggesting he might drop Pelé because of his supposed short-sightedness. Briefly before the World Cup, he was sacked, and replaced by Mário Zagallo, who had scored the other goal against Mexico in 1962.

What followed was probably the greatest World Cup performance by any team. Brazil won all six games and did so playing brilliantly attacking football. Tostão was the center forward, with Pelé just behind him, Jairzinho a goal-scoring winger on the right, Rivellino on the left and Gerson creating from deep in midfield alongside the scrapper Clodoaldo. But this was a very fluent team with attacking fullbacks in Carlos Alberto and Everaldo. It played in beautiful patterns and it enraptured the world.

And at its heart was Pelé, whose spirit of improvisation encapsulated all that was best about that Brazil, attempting a shot from the halfway line against Czechoslovakia and dummying the Uruguay goalkeeper Ladislao Mazurkiewicz in the semifinal. He opened the scoring in the final with a classical header and then capped the tournament with a perfect lay-off for Carlos Alberto to score Brazil’s fourth. There was an artistry to him and that side that inspired not just admiration but love. “His influence was collective,” Zagallo said in an interview in The Blizzard. “He made things easier for the others, because he attracted the marking. So his desire to show his talent was something completely natural.”

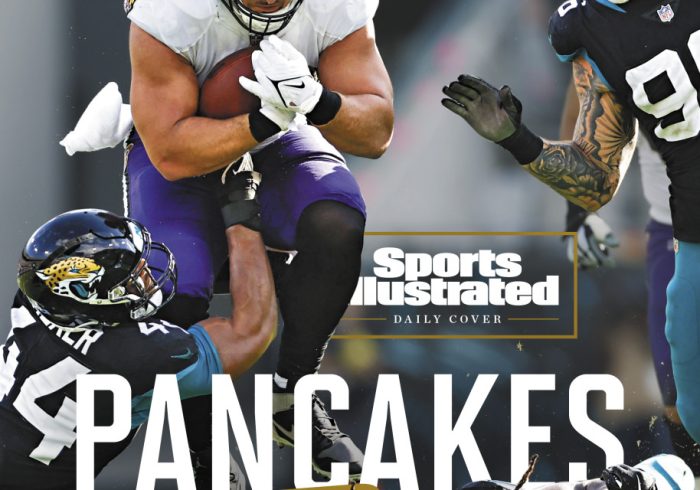

The 1970 World Cup, where Pelé starred, was the first to be broadcast in color around the world.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

The 1970 World Cup was the first broadcast via satellite. Part of its impact was that it was beamed in color around the world. Mexico was hot, exotic and across the sun-bleached green of the grass was a team of artists in shorts of the purest yellow and shorts of cobalt blue. It seemed the height of modernity; even the ball was named Telstar after the satellite that made the broadcasts possible. But in football terms, 1970 did not represent the future; rather it was a throwback.

The samba stereotype of Brazil as a happy-go-lucky side plucked from the beach was always nonsense, and Zagallo’s side was constructed with internal balance. But still, it was the football of individuals. Zagallo told Pelé: “The team is going to be you and 10 more,” at a time when the game was turning to the systems that had dominated in 1966. Pressing, though, with the fitness levels of the time, simply wasn’t possible in the heat and altitude of Mexico.

And so the 1970 Word Cup stands almost out of time, a hint of a direction football might have taken. By the time the next World Cup came around, João Havelange had been elected president of FIFA, and football’s corporate age had begun. Pelé’s age of promotional work had already started. To blame him for not standing up to the dictatorship of General Médici is probably unreasonable. The majority of people in difficult times keep their heads down and seek merely to survive, but Pelé seemed almost willfully naive as he and the team were used by the regime.

But there was also more traditional PR work. Sometimes it feels as though there was nothing Pelé did not at some point advertise. He appeared in a soap opera. He advertised Puma and Pepsi, Mastercard and Viagra. At one point he had locks of his hair heated under intense pressure and sold the diamonds that resulted. Everybody, of course, has a right to maximize their revenues and perhaps especially those who grew up in the sort of poverty Pelé experienced. He was perhaps especially conscious of money after almost being bankrupted early in career by bad decisions made by a business partner.

But still, as Tostão noted, there was something disconcerting about the way the public mask consumed everything else. “The man Pelé doesn’t come through,” he told The Blizzard. “It’s Pelé the myth, Pelé the publicity billboard. That’s what he is now—an advertising man. He does it very well. He’s the Pelé of the business! He behaves well, he sells products. He’s admired everywhere, but there’s always a distance, because everything he does is planned.” The nadir perhaps came with the FIFA 100, a list of the world’s 100 greatest living footballers drawn up by Pelé in 2004 as part of FIFA’s centenary celebrations. Determined not to offend anybody and to tick every box, it included 125 names, scrupulously and slightly farcically drawn for across every confederation.

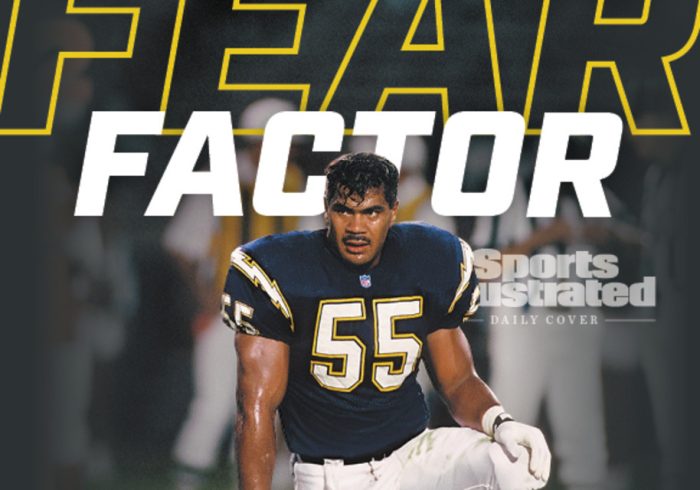

Pelé finished his playing career with the New York Cosmos in the old NASL.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

Joining the New York Cosmos in 1975, of course, was itself a business decision, for all the well-intentioned talk of developing the game in new territories. Pelé had wanted to retire in ’74, had even played his farewell game for Santos, but further business losses forced him to reconsider. He received $9 million to sign for Warner Communications, plus 50% of any revenue generated by the franchise under his name. His time in New York was a huge success commercially—Pelé was the ideal face for the franchise—and the Cosmos won the Soccer Bowl in 1977, at which Pelé retired. Tostão has been skeptical of his “vanity” in quitting the Brazil national team after the World Cup in ’70, but a more generous interpretation is perhaps that he had an acute sense of timing.

To take his place in the squad, the Cosmos signed England forward Dennis Tueart. When Tueart arrived in New York, Pelé was still training with the franchise despite having announced his retirement. He was struck by the “boyish enthusiasm” of a player who had won everything and had recently announced his retirement. Pelé continued to perform promotional work for the Cosmos. Wherever he appeared, Tueart said, in the U.S. or abroad, it was “Hollywood on the road.”

Yet for all the fuss around him, Tueart remembers Pelé as “very, very humble. He always gave you a hug and would treat you like you were a long-lost pal.” Yet “he always went onto the field to win.” He had “balance, technique, strength—great bulging thighs—great acceleration, yet never lost control.”

And that, perhaps, is how Pelé should be remembered. He became a figure who transcended football. He was painted by Andy Warhol who joked that he would have not 15 minutes, but “15 centuries” of fame. On his 50th birthday he sat on a giant birthday cake at San Siro while a choir sang to him after which he played in an exhibition game for Brazil against the Rest of the World. He became a blank canvas for marketers, his public image one of ineffable blandness—and that made him vaguely ridiculous, obscuring what he was.

And what he was, what gave him that fame, was one of the very greatest footballers there has ever been. He came from the humblest origins yet, by the age of 17, he was already regarded as the best player in the world. He won three World Cups and a whole lot more besides. He was the first footballer to be a global star. Was he greater than Diego Maradona or Lionel Messi? Frankly, it doesn’t matter. He was great, and the old footage shows him as such, despite our natural tendency to prioritize modernity.

Beyond Pelé the brand, what should be remembered is Pelé the footballer.