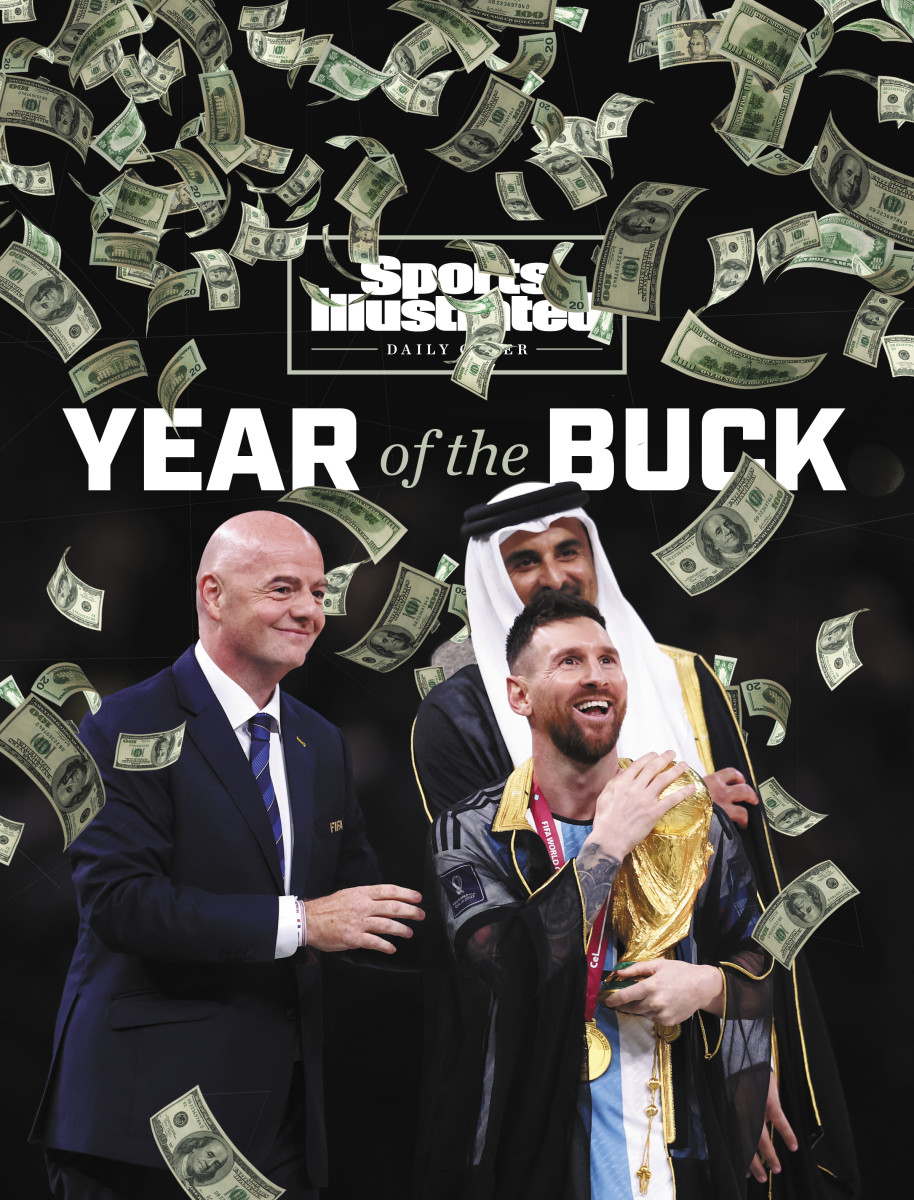

As 2022 winds down, Sports Illustrated is looking back at the themes and teams, story lines and through lines that shaped the year.

As the tastemakers gathered to consider a Sportsperson of the Year for 2022, here’s one name that, decidedly, didn’t come up in conversation: Dustin Johnson. Competitively, the mid-career golfer did fine, winning an event in Boston and embedding himself in the top 10 on plenty of leaderboards. But it was nothing extraordinary, as he himself was quick to concede. Summarizing his ’22 campaign to The Palm Beach Post, Johnson said flatly: “I feel like it should have been a lot better. I played good. I didn’t play my best.”

The market suggested otherwise. By an order of magnitude, Johnson had the best year of his career, earning enough money to make hedge fund managers spit out their Château Margaux.

Johnson’s financial haul this year? He won more than $36 million in prize money and bonuses. And then there was the $125 million lavished on him when he decamped to a new golf circuit for four years. Prorated, that “signing bonus” equates to more than $31 million a year. Add that to the on-course earnings and that’s almost $70 million (before endorsements), roughly the same amount Johnson earned in prize money over his previous fifteen years on the PGA Tour.

Johnson, of course, was one of the many financial beneficiaries of LIV Golf, the Saudi-backed breakaway tour that used its petrodollars to rock the foundations of golf in 2022, reteeing, as it were, the entire sport’s power structure and economy. Consider that in June, when South Africa’s Charl Schwartzel triumphed at the first LIV tournament, few fans were on hand, and there was no television coverage for the event’s three rounds—or 54 holes; hence the roman numerals LIV—which streamed on only YouTube and Facebook Live.

Nevertheless, Schwartzel was conferred $4 million, then the highest winner’s purse ever disbursed to the winner of a golf event. As no less than Tiger Woods—who resisted an offer of, reportedly, $700 million to decamp—said of LIV, “It’s an endless pit of money.”

That might as well have been the motto for all of sports this year. We are, of course, long past the days when pro teams were owned by the local car dealers, ticket revenue mattered and the whole sports enterprise was simply a small corner of the culture, where fans could lose themselves for a few weekend hours. But 2022 was the year that sports firmly established itself as a full-fledged economic sector. The trifecta box of a global recession, lingering global pandemic and global conflict? Sports was immune to it all. The pit of money is, officially, bottomless, endless.

The highest expression of this excess may have been the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, where this number wafted around: $220 billion. Two hundred twenty billion dollars. That, we were told repeatedly, was what Qatar spent to stage this quadrennial event.

Dustin Johnson was one of the many financial beneficiaries of LIV Golf, the Saudi-backed breakaway tour that used its petrodollars to rock the foundations of golf in 2022.

Joe Scarnici/LIV Golf/Getty Images

Billions and millions are, to many, the new passer ratings or WHIP of sports coverage and sports fandom. We reflexively cite the figures, but they are often abstractions, easy to gloss over without full consideration. But let’s pause and unpack that $220,000,000,000 figure from Qatar. Two hundred twenty billion dollars? That’s more than double the combined spending that went into the previous eight World Cups. Two hundred twenty billion dollars? For that price, the Qataris could have purchased every NFL team … with, potentially, enough funds left over to purchase every NBA team, as well.

That extrapolation is based on the $4.65 billion price paid in 2022 for the Denver Broncos and the $4 billion fetched for the Phoenix Suns and Mercury last week. It was a decade ago that a group of investors purchased the Philadelphia 76ers for $290 million, their investment having spiked more than 10 times in 10 years. Then again, that’s what happens when the next NBA media rights deal is expected to triple the current deal, and land in the $75 billion range.

Which would still put the NBA well behind the NFL, generating, tracking, as it is, for $25 billion in overall revenue by 2027—a figure that would stack up favorably against many publicly traded companies. Not that the NFL has a monopoly on football lucre. College football is surging, too, especially Power 5 programs, like those in the Big Ten, which is no longer a group of 10 teams but is bigger than ever. Once consigned to the Midwest, the conference will soon be up to 16 member schools, its footprint spanning from New Jersey to Southern California, this after seducing UCLA and USC. That’s what happens when the conference secures $1 billion from multiple networks in exchange for the rights to air games.

Air, as opposed to stream. Though that’s a possibility, too. This was the year Apple got into the sports game, agreeing to pay Major League Soccer $2.5 billion over 10 years to carry all regular season and Leagues Cup (MLS vs. Liga MX competition). Amazon finished its first season as home to the NFL Thursday-night games, an overall success despite no help from the league’s schedulers. (Netflix walked back its desire to get in the live sports game. The reason was simple: The rights have gotten too expensive. “We’re not anti-sports,” CEO Ted Sarandos told investors, “we’re just pro-profit.”)

With all this money sloshing around the sports space, it’s only right that some of it—in some cases, thanks to unions, half of it—redounds to the players. So it is that when the NBA’s new media deal is signed, say, Giannis Antetokounmpo, could conceivably earn $100 million per season … which is more than what Michael Jordan ($94 million) made over his entire career. With straight faces, we can debate whether Aaron Judge’s new deal with the Yankees sells him short when he is making “only” $360 million over nine years. Meanwhile, 2022 was the year an NFL team shamefully lavished a quarter of a billion dollars on Deshaun Watson.

That kind of spending isn’t only in the realm of U.S. sports. (An example among many: In December, Cristiano Ronaldo turned down more than $100 million per season to play for a team in Saudi Arabia.) And it’s not just “professional” athletes. Owing to name, image and likeness deals and the attendant vessel, the almighty transfer portal, quarterbacks and point guards and even some gymnasts can now generate revenue for themselves as well as for their school.

Those slurping at the sports money trough are not just athletes and owners. Head coaches can earn in excess of $10 million per season. Coordinators in college football can earn more than $1 million. A top football broadcaster like Troy Aikman can earn $1 million per game, more than he did 30 years ago when he was being pursued by 300-pound opponents seeking to drive him to the turf.

Late-stage capitalism being what it is, there are complicating factors, if not outright losers. Whether it’s paying for tickets or a quiver of streaming services, it’s never been more expensive to be a fan. College athletes are still scandalously underpaid—their ability to earn NIL revenues from third parties is a start but doesn’t address the fact that they remain uncompensated for the valuable work they are providing their schools. Sports gambling, another revenue stream, may have moved in from the margins and found social acceptability. But when colleges get a kickback for getting students to sign up for accounts, it is nothing if not a moral failure. Sportswashing—using the appeal of competition and events to launder and rehabilitate a country’s reputation externally, and distract internally from human rights abuses and other bad acts—is a trend gaining valence.

Sports gambling, another revenue stream, may have moved in from the margins and found social acceptability. But when colleges get a kickback for getting students to sign up for accounts, it is nothing if not a moral failure.

Rich Graessle/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Still, sports should be the envy of so many other sectors. The consumer base is global, young and tribally loyal. The growth is unchecked. And there remains room for so much more. There are emerging markets only beginning to be explored—as the various American and European leagues opening offices in India and Africa suggest. There are still revenue streams that can become rivers. New economic models will help target new profit centers and find efficiency. The dynamic pricing used so effectively (ruthlessly?) by brands from Ticketmaster to Uber? What if the leagues pivoted away from the certainty of television contracts, and forced networks simply to bid week-to-week on individual games?

Maybe most critically, all of this commerce benefits the underlying product. When, say, LeBron James has the resources to spend $1.5 million, as he professes to, “on my body”—all those nutritionists and trainers and massage therapists—everyone wins. He plays, undiminished, deep into his 30s availing himself of all those years and supermax contracts and endorsements. Fans enjoy his services and form an attachment for all those additional years. Teams and leagues get two decades, not one, out of their prime assets.

In 2022, Roger Federer and Serena Williams both retired. Both are 41 and already, reportedly, billionaires. Other peers played on, incentivized by the red-hot sports market and benefiting from the career extension that money can buy. Tom Brady has, of course, been on the planet for 45 years, and is a singular (and now, single) quarterback. Justin Verlander is fresh off winning the World Series at age 39. In hockey, Alex Ovechkin, 37, continues his pursuit of Wayne Gretzky’s 894 career goals, “The Gr8 Chase,” a term that Ovechkin has, naturally, trademarked.

On Dec. 13, he scored a hat trick that included his 800th career goal. That night, fans, worldwide, watched live, something that would have been unthinkable when he started his career. Many saw accounts on their sports bets wax and wane. Ovechkin was earning his eight-figure salary. In celebration of the milestone, he peeled off his helmet, revealing a shock of gray hair, and pointed to his jersey. Fittingly, it read “Capitals.”