In the early 2000s, Esquire published a column called “The Indefensible Position.” This was a sort of proto-hot-take clearinghouse, intended sarcastically, presaging a time when every idea—no matter how implausible, counterintuitive or just flat wrong—was given a platform. Writers took turns mounting seemingly unpardonable arguments, such as “Smoking Has Its Benefits” and “Adultery Is Good for Your Marriage.”

The column debuted in 2001, the same year that a Las Vegas sports promotion called Zuffa (Italian for “fight”) paid $2 million for the rights to stage the Ultimate Fighting Championship: two men––and at the time the fighters were exclusively male––beating the bejesus out of each other while locked inside a steel octagon. Though not in the pages of Esquire, plenty of pulp and pixels were devoted to the supposed indefensibility of cage-fighting, an activity that at the time was banned in most states (and banned from pay-per-view, which is really saying something).

We all know how this story broke. Many of us (myself included) grew accepting, then fond, of the UFC, which steadily penetrated the defenses of the mainstream. We became less squeamish. The athletes revealed themselves as generally likable and decent. The fight cards grew to include women. Those health and safety concerns were largely assuaged. The predictions of death, happily, never came to be.

In 2016 the UFC was purchased by IMG/William Morris for $4 billion, a 2,000x return on Zuffa’s investment. Today, every state has legalized and sanctioned mixed martial arts, the UFC is helping to prop up ESPN’s streaming service, and fights have even aired on network television.

Emboldened by this success, the UFC is now doubling down—emphasis on down—and taking a truly indefensible position. For years, frontman/president Dana White has evangelized the virtues of slap fighting, and in November—in conjunction, criticality, with UFC events––he announced that he would be joining forces with UFC founder Lorenzo Fertitta, COO Lawrence Epstein and longtime TV producer Craig Piligian in promoting Power Slap, “the premiere competition for the world’s best open-hand strikers!” (Let’s pause here and note the ensuing unpleasant irony: Over New Year’s, White appeared in a video that went viral, striking his wife, Anne, with an open fist. Afterward, he said, “There’s never ever an excuse for a guy to put his hands on a woman,” and “all the criticism that I have received… is 100% warranted.” But, stating the obvious: A slap-fighting league headed by a man who recently slapped his wife makes for, at a minimum, deeply problematic optics.)

Slap fighting is … well, essentially, what you think it is. Two combatants stand opposing each other, as if playing Family Feud. But rather than reflexively naming, say, a popular dessert or a reason someone quits their job, each contestant cocks back an arm, rotates their hips, opens a hand and goes full Will Smith on their opponent’s face.

There are rules. And penalties. Both for the slugger (no “clubbing,” meaning hits to the ear or chin; no illegal wind-up) and the sluggee (no flinching; no blocking). There are weight classes. There are men’s and women’s divisions. There are, inevitably, “power slap girls” to titillate fans between bouts. There’s a clock, ticking off the 30 seconds that Combatant A has to slap Combatant B. And then the 30 seconds Combatant B is allowed to recover from the aforementioned slap. Like in MMA and in boxing, bouts are judged on a 10-point-must system, and victory comes via knockout, by TKO or by points. The winner is often, literally, the last one standing.

Mixing sports metaphors here, to get this across the finish line the Power Slap group dusted off its playbook from 20 years ago, essentially revisiting the tactics that worked so well in bringing MMA in from the margins:

1) Make a libertarian, assumption-of-the-risk argument. Fighters know what they’re getting into when they agree to do this. No one is fighting under duress. Will everyone take to this form of entertainment? No. But should it be banned? No.

2) Set up a reality show, winnowing down the hopefuls as they train, culminating in a competition. This gives fans a chance to connect with the central figures and allows skeptics an opportunity to acquire an acquired taste. During a November press conference in New York, White announced that TBS—not, pointedly, ESPN, the obvious television partner—will air an eight-episode Power Slap series. (The series was originally slated to debut Jan. 11, but after the video of White striking his wife was released, TBS delayed a week. TBS has not commented on the incident.) Also, to douse the skepticism, the league has attracted celebrity investors. Hey, if it’s O.K. with Arnold Schwarzenegger …

Schwarzenegger backed a slap fighting championship last year in Columbus, Ohio, adding a dash of credibility to the, ahem, sport.

Gaelen Morse/Getty Images

3) Lean into the regulation. Getting the go-ahead from a state athletic commission, starting in Nevada, is the first step toward legitimacy. Power Slap league gained approval from the NSAC in October.

4) Boxing, with its repeated concussive blows and dubious promoters, makes for a convenient straw man comparison. Here, on cue, is White: “The bottom line is: In a boxing match, guys get hit with 300 to 400 punches in a f—ing fight. These guys are going to get hit with three slaps.”

Predictably, the announcement of Power Slap’s launch drew its share of criticism. This was a lowering of civilization’s limbo bar. One commentator suggested that slap fighting is what you would get if a 13-year-old started a sport. Another compared it to a “NASCAR race with intentional car crashes.”

Unlike the slap fighters, White could defend himself. “I saw a lot of the goofballs”—the goofballs being the media—“talking s— about What’s next, mallets? Stupid s— like that,” White said at the launch press conference. “For these morons to be talking all that s— about the athletic commission … the athletic commission did the right thing. So did we.”

He was more measured when talking to Sports Illustrated on the matter, but he stressed the same points. Slap fighting has been popular for years in Poland and Russia; when viral highlights started popping up in White’s instagram feed, he concedes, “I became fascinated.”

But does he really think there’s an audience for this beyond social media? “We’re going to find out, brother. It has, on social media, like, 250 million hits, or something like that.”

Is it safe? “If you look at the incredible fights that have happened in the UFC, there has never been a death or a [life-threatening] injury, because we make sure guys get the proper medical testing before, during and after the fight. … Once you have these things in place, you now have a sport, and you’re legit.”

Not so fast.

When advocating for the UFC 20 years ago, Zuffa rightly stressed the elite athleticism, conditioning and skills of the fighters. These were not goons straight out of the drunk tank trading haymakers. They were jiu-jitsu black belts and All-American college wrestlers and converted professional kickboxers. These were also practitioners who knew how to defend themselves, control their destiny and conceive a strategy to counteract an opponent.

In slap fighting, short of biting your mouthguard and hoping to hell that your opponent obeys the rules against clocking you in the ear, there’s little for the “defender” to do but stand there and take it. “There’s nothing sporting about it with no defense,” says Chris Nowinski, pro wrestler turned neuroscientist and cofounder of the Concussion Legacy Foundation. “[Slap fighting] is perhaps one step above the old Bumfights videos. So sad.”

One could argue that this foray into slap fighting by UFC execs is itself a clever bit of jiu-jitsu. Slap fighting pushes boundaries of acceptable and, inasmuch as MMA still struggles for mainstream acceptance, well, it now looks downright quaint (and hardly marginal) compared to slap fighting.

But there’s a more convincing argument: Slap fighting has the effect of delegitimizing the UFC and validating old criticism, wrongheaded as it might have been, that the organizers were always just building a business based on bloodlust. MMA may never threaten the NFL, as White long ago predicted. But it has its real estate in the current sportscape, and it has come a long way since being dismissed as human cockfighting. Why threaten that progress by associating with something as base as slap fighting?

That, however, is just the collateral damage. The real damage is of the physical nature. We—fans, media tastemakers, pop culture creators—might differentiate slaps from punches. But neurology doesn’t. Slap fighting, says Nowinski, “is just exploitation of people who don’t understand brain injuries or CTE.”

Jason Mihalik agrees. He’s the co-director of the University of North Carolina’s Matthew Gfeller Center, which studies traumatic brain injury. He says that a slap would normally produce lower forces than a closed-fist punch, because it would involve soft-tissue-on-soft-tissue contact. “In slap fighting, however,” he says, “there are a couple considerations that change this scenario. One: The slap mechanism is designed to magnify rotational acceleration mechanisms.

“Two: The impact point I’ve observed in many [slap-fighting] videos is not initiated by the hand’s soft tissue but, rather, the bony architecture of the carpal bones at the base of the hand.

“Three: Participants do not appear to be allowed to defend themselves.” (Correct.)

“People are going to risk their brains to make a few dollars?” asks Alessio. “What does that say about all of us?”

Gaelen Morse/Getty Images

Dr. Anthony Alessio, a sports neurologist and the director of the University of Connecticut’s Neurosport program, agrees. “The human brain was not meant to be whacked around,” he says. “You have to look at vectors. In [slap fighting], you’re banging the brain around on a pivot—the cervical spine. So, first there will be a lot of neck injuries from the head jerking. Then the [risk is a] contrecoup injury, where the brain will bounce to the direct opposite side from the point of impact. Slap someone on the right side, the brain will bounce against the skull and [the injury] would be on the left side.”

Power Slap’s format, he says, compounds matters. The idea that competitors will take not just a blow, but a series of blows, increases the health risk dramatically. “The brain is a very resilient organ,” says Alessio. “But it needs time to heal. Are you going to get brain injuries when you keep getting slapped in the head? Yeah. Of course. People are going to risk their brains—their ability to recognize their family when they get older—to make a few dollars? What does that say about all of us?”

Sadly, he is not just speaking theoretically. Last year in Poland, 46-year-old Artur Walczak, a former MMA fighter and strongman competitor, participated in a slap-fighting event called—apparently without irony—The PunchDown Gala. After taking a brutal blow to the head, Walczak fell to the ground and showed what medical officials later called “disturbing neurological symptoms.” He lapsed from consciousness, went into a coma and never awoke, dying of multi-organ failure resulting from irreversible damage to the central nervous system.

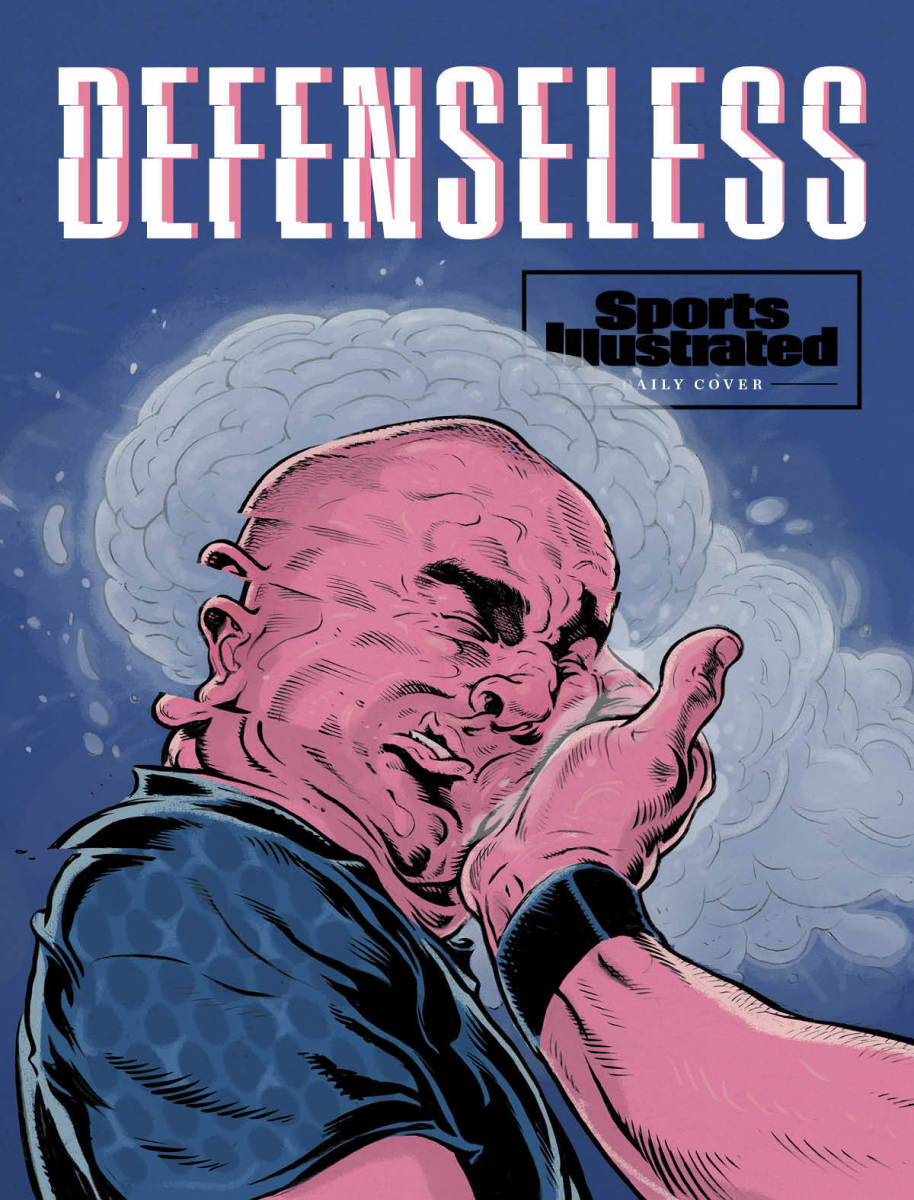

No amount of medical testing or drug testing would have saved him; a humanizing reality show would have done his family no good. He was defenseless. While doing something indefensible.