Ron Washington joined the Braves in 2017, signing on as third base coach after a long, winding path through the league and across the game. He brought his morning routine with him.

This is how that looked in spring training. His infielders had to be on the diamond each day at 7:30 a.m. Which meant that, starting around 7 a.m., their coach could enjoy a cup of coffee in the dugout in peace. This was about as strong a guarantee as Washington could get: At that hour? No one would bother the veteran coach. Sure, every organization had a few guys who liked to get to the clubhouse early, and he’d welcome any company to join him for a cup. But there was no one who would ask him for anything. He wouldn’t be approached by a player who wanted to run his famous infield drills or have a serious discussion about something or, hell, get ready on the field at all. No one did any of that before 7:30 a.m.

Except for Austin Riley.

Washington noticed the kid over his coffee one morning, and the next morning, and the next. The 19-year-old third baseman had just finished his first season of A-ball. He was years away from breaking through. But he was always the first one out on the field in those early days of spring, all by himself, and he jumped at the chance to do some drills when offered. So coach and player developed a little routine of their own. They never planned ahead or set a time. They didn’t have to. Every morning, Washington would sit down with his coffee, and every morning, Riley would come out soon after. They would run through some work and chat. Washington has structured his drills to require only a few minutes; Riley would typically be finished with them before anyone else was out on the field to see. And then the pair would go about the rest of their day.

“He’d come around, and I never told him no; I just put my coffee down,” Washington says. “But occasionally I’d mention to him, You know it’s not 7:30, right?”

He did. But he also knew that he wanted to be out on the field as much—and as soon—as he could.

The early-morning teenage prospect debuted in the big leagues two years later. Now he has the biggest contract in the history of the Braves, a 10-year, $212-million extension that was announced on Aug. 1.

The deal secured Riley’s place as the cornerstone of a young, enviably talented roster for the foreseeable future. It caps an impressive stretch for him: After emerging as one of the game’s strongest power hitters last year—he hit 33 homers, finished seventh in the MVP voting and won the Silver Slugger—on a Braves team that ultimately won the World Series, he’s been enjoying an even better followup season. And he now has the contract to show it.

This background might give a familiar shape to the story of Riley’s younger self: To picture him as the first one on the field each morning is to get the classic imagery of a star athlete waking up early to grind away. It’s a cliché. But it’s such a reliable one for a reason. (And Riley, by all accounts, really still is the kind of player to show up consistently early and put in the work.) Yet this story can be framed in some ways that are perhaps more revelatory. It’s the story of Riley’s relationship with Washington, the person in the organization whom he credits most with helping him deal with his early struggles and understanding what it means to be a big-leaguer. It’s a story about his embrace of routine—someone who likes what he knows and knows what he likes. And it’s a story about how much he genuinely enjoys being on the field, appreciating how it feels alone in the quiet of the morning, giving him space to work and to think.

In other words, yes, the early-morning drills make this a story about how Riley ended up in a position to be offered 10 years and $212 million. But everything else makes it a story about why he took it—why he decided to forgo free agency, with potentially even more money and certainly more flexibility, to stay right where he is.

“Now,” Riley says, “I can just play baseball. Now I can appreciate the game that much more.”

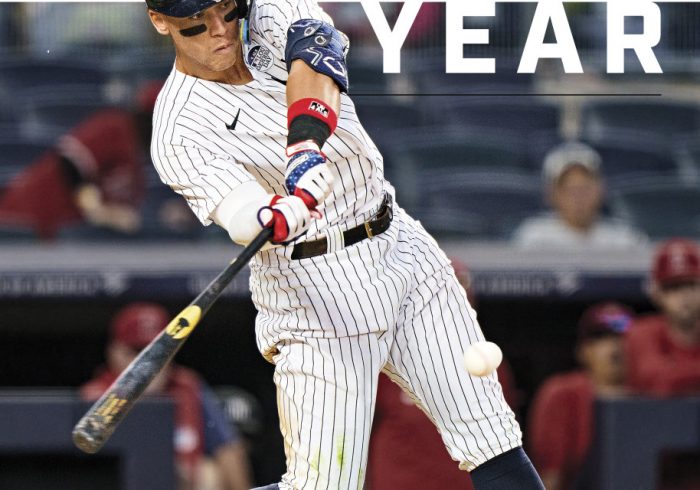

Riley hit .320 in the World Series last year, after batting .303 with 33 home runs during the regular season. In many ways, he’s been even better in 2022.

Rich von Biberstein/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Atlanta’s front office has made a habit of extending young talent. The Riley announcement was notable for its length (through 2032, club option for ’33) and its sheer size (again: the biggest in franchise history), but it was hardly unique. Riley shares an infield with first baseman Matt Olson (extended through ’29, club option for ’30) and second baseman Ozzie Albies (through ’25, club option for ’26 and ’27), and they play in front of an outfield with Ronald Acuña Jr. (through ’26, club option for ’27 and ’28) and Michael Harris II (through ’30, club option for ’31 and ’32). These extensions have built upon one another—with each additional deal making it easier for players and executives alike to have a sense of the future and what it means to commit to the team long-term.

There are naturally some commonalities among the deals. Any extension like this requires a player to have early success—and for most of these, the success was not just early, but immediate. Acuña was named Rookie of the Year; Albies was productive in his first season and became an All-Star in his second. Though Olson began his career in Oakland before getting traded to the Braves, he received votes of his own for Rookie of the Year, and Harris is now a favorite for the award in 2022. But there’s somewhat of an outlier in the group: Riley.

That is true of his extension itself—longer and more lucrative than any of those above—but also of what it took for him to get there. Riley did not have that kind of immediate success in the big leagues. But he thinks he’s better for it.

“I needed to go through those struggles to learn how to deal with failure,” he says now. “And I think that’s kind of instilled that positivity. You’re going to go through those phases, and it’s how you deal with them and keep moving forward that’s how you’re going to ultimately trend upward.”

He broke into the majors with a hot streak in 2019. For a few weeks, his performance matched the best of the reports on him as a prospect: In his first 15 games, Riley was 21-for-59 with seven home runs. But then it started to fall apart. Opposing pitchers figured out that he was extremely vulnerable to anything in the top of the zone, and as he struggled to make that adjustment, other problems spread to the rest of his game. The Braves were using him primarily in the outfield—though he came up as a third baseman, there had been early questions about his ability to stick at the position long-term, and the team had been so eager to get his bat in the lineup that it tried him at left field that summer instead—and he was struggling to find his footing there. It felt like nothing was going right. After posting a 1.143 OPS for the month of May, when he first came up, Riley put up a paltry .480 for July. He was briefly sidelined by a knee injury in August. The forced time away felt almost like a disguised blessing.

“He was really in a tailspin,” says Braves general manager and president of baseball operations Alex Anthopoulos. “Had he not gotten hurt, candidly, he was likely going to get sent back down. … I don’t know how much longer we would have allowed that to continue.”

This was the first time Riley had truly struggled with baseball. It wasn’t that he’d cruised through the minors—to the contrary, he’d needed some time to crack each level, and none of it had come very easily. But he’d always felt personally in control throughout that process. He’d been able to figure out how to make it through each challenge with enough work. Now, that didn’t feel like the case. For the first time, Riley was scared that he wasn’t going to be able to find a way out. As he’d become more anxious before his injury, he’d grown more desperate, and it seemed as if he’d lost control of everything. “It spiraled into swinging at a bunch of stuff,” he says. “I remember very vividly in ’19, just going up there and having no command. Just swinging at the first pitch, the second, it didn’t matter. It was just anything for a hit.” And none of it had worked. (He had a strikeout rate of 43% that July.) He was on the biggest stage—where he’d always wanted to be—and he was failing.

“I hit the panic button,” Riley says. “Hard.”

For a few weeks, he simply felt lost. And then he committed to pulling out of it. When he returned from his knee injury that fall—and particularly over the offseason in the winter—he zeroed in on his approach at the plate. What he wanted to do, Riley says now, was “understand [his] swing”: So much of hitting had come naturally to him before that he simply had never required a deeper, more analytical understanding. Now he did. He logged hours with former Braves minor league hitting coordinator Mike Brumley. They worked on figuring out which sources of data were helpful to him and which just felt overwhelming, and they spent lots of time on pitch recognition: He needed to learn how to lay off those high ones. Riley felt like he was finding balance, and gradually he began to feel more confident again.

The impact wasn’t immediate: Riley’s performance in 2020 was still fairly uneven, with an 86 OPS+, identical to what he’d posted across the ups and downs of ’19. But he seemed less shaken by the experience. “To his credit, he kept his head above water,” Anthopoulos says of Riley that season. His strikeouts dropped significantly: A K rate of 36% from ’19 became 24% in ’20. His overall production may not have budged much, not yet, but the progress in his approach was clear.

“You’re going to give him every benefit of the doubt,” Braves skipper Brian Snitker says of his approach to managing Riley through that stretch. “You’re going to give him the opportunity to stay out there, because you know what can happen; you know the impact he can have.”

Then there was his defense. The team had ended its outfield experiment with Riley and was willing to give him more time at his original position of third. And that meant lots of work with Washington—both physically and mentally.

Washington has been instrumental in Riley’s development from a 19-year-old prospect into an All-Star third baseman.

Dale Zanine/USA TODAY Sports

This was not a special undertaking specific to him. Instead, it was simply the infield drills Washington runs with each of his fielders daily, the same ones Riley had started back in spring training in 2017. The practice is part baseball, part therapy, part church. It all takes only four minutes. (Any longer, Washington says, would be too long: Five minutes is a commitment. But four minutes is something anyone can give.) For the first two minutes, Washington tosses ground balls to the fielder, and for the last two, he gets out his fungo bat. They are some of the most basic drills a fielder can do. But therein lies their magic: They are deliberately boring, Washington says. He believes in the importance of doing boring work every day, because if a fielder never skips that kind of work, he never ends up in a position where he really needs it. A player never has to go back to basics if he already hits the basics every day. A coach never has to take a guy aside for a big, one-on-one discussion that might get inside his head if he already has a few minutes of casual one-on-one time built into his daily schedule. And that accompanying conversation is just as important as the drills themselves.

“You learn a lot,” Washington says. “It’s not just me hitting ground balls. We talk a lot of stuff—about baseball, the mental side of it, how to bounce back from adversity. There’s a lot going on down there on the ground other than me hitting balls to ’em.”

The work was almost meditative for Riley. The practice was reassuring—a space to chat and free his mind and let himself breathe. The conversations with Washington naturally focused on defense. But the approach gave him confidence through every part of his job.

“He just kept telling me … ‘This is part of the game. You have to go through this to grow as a player,’” Riley says. “He just kept making sure I understood that.”

If he’d once felt pressure from how quickly some of his fellow prospects had become successful big-leaguers, Riley was now beginning to realize that he could develop at his own pace. “I felt like when Ronald came up, when Ozzie came up, it was like they immediately blew it out of the water,” he says. “And for me it was just not that. … Every player is different.” He recognized that people in the organization believed in him. And just as importantly, he understood they were giving him the time and space to show that belief was well-placed.

“I felt like in those years, the biggest thing was just to continue the encouragement, just tell him to continue to keep going,” says Braves shortstop Dansby Swanson, the longest-tenured member of this infield. “Because he obviously is an incredibly special player. He’s gifted in so many ways—he sees things on the field in certain ways that most people don’t.”

When Riley put it all together in 2021, then, it felt like an organizational triumph almost as much as a personal one. He stood out as a bona fide power hitter with the ability to hit the ball to all fields. He led the team in Baseball-Reference WAR with 6.1. Riley posted a 135 OPS+ and delivered in the playoffs, too, with a series of clutch hits en route to the World Series. And to Washington’s delight—“I never was wrong about him”—he showed that he could stick at third.

“The work ethic, the character, the kind of teammate he was, all those things were phenomenal. And he obviously had tremendous talent,” Anthopoulos says. “So in terms of betting on the person … it made for maybe some ups and downs. But you combine those things, almost every time, it gets to work out.”

Riley has been the best player for the Braves in their title defense season.

Rich von Biberstein/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Riley came into this season building off his success from the last one. He started the year strong and stayed that way; he continued to improve in areas like plate discipline (a career high strikeout-to-walk ratio) and hard contact (another career high in exit velocity) and was rewarded as a first-time All-Star. As the Braves try for another division championship in the NL East—with a crucial weekend series beginning Friday against the Mets—Riley is once again their team leader in WAR. That’s been true for almost the entire season.

All of which naturally led to talk about an extension.

There were initial discussions in the spring, when both sides were preparing for Riley’s first arbitration hearing, Anthopoulos says. Those conversations were positive but did not lead to anything concrete. So they agreed to revisit the subject later—perhaps next season, they figured, when the third baseman had built up more of a track record.

“It probably made sense for both parties to wait,” Anthopoulos says, “because last year was the first season he really put it together.”

But as Riley continued to tear through 2022, they decided to come back to the table earlier than anticipated. This time, the conversations turned serious in a hurry.

A deal like this might seem clear for both sides. A front office gets years of talent for what could potentially be quite a bit below the market rate. A player secures generational wealth upfront, protecting against future injuries and slumps, even if he realizes he might be passing up a hypothetical opportunity to earn more in free agency. But the process of negotiating can be messy and fraught.

For Riley, there was little question about where he wanted to be. He knew that he liked the idea of staying in Atlanta long-term: He’s originally from Southaven, Miss., which means the Braves are the closest team to his hometown. He’d tried to picture himself playing elsewhere—out west? up north?—and found it difficult. Meanwhile, he was gratified by the support and patience the organization had shown him already in his young career, and he thought the club was somewhere he could continue to grow and push for his best. And with all of the other team extensions—knowing who he would be sharing an infield with for years to come—it seemed easy to commit. “When you have that comfort level, you know what to expect from each other, you kind of have that bond,” he says. “Anytime you can have an infield that’s going to be together for a while, that can grow close together and really just play for each other, I think it shows.” He wanted to be part of that: This team, this infield, felt like home to him.

But if it’s simple enough to intellectually grasp the meaning of hundreds of millions of dollars and a decade of life, it can be very, very hard to do so emotionally.

“It’s obviously life-changing, generational, all of that,” Riley says. “But that was almost beside the point.”

There was one crucial thing that had changed for Riley since that first round of contract talks. His wife, Anna, had given birth to the couple’s first child, a boy named Eason, at the end of April. And while Riley was adjusting to fatherhood, he was gaining a new perspective on what it might mean to sign this kind of deal. It had previously been difficult to conceptualize the difference between six years and eight and 10: He understood it logically, of course, but it had seemed all but impossible to actually picture what those years of his future might look like. Now, he had one very simple, concrete measure to go by.

“When the contract is up, he’s going to be 10,” Riley says of Eason. “That’s pretty crazy.”

His son gave stakes to the dollar amount—to the value of stability—and a frame of reference to the years. He’d already thought this was what he wanted. Now, he knew.

For Anthopoulos, meanwhile, the process was stressful in its own way. He had plenty of experience with negotiating extensions. But he’d never done one quite like this.

“We’ve never done that type of money,” he says. “We’ve never done those types of years. … You understand that there’s risk involved in aging, health, it’s a hard game. Teams make adjustments to you. It’s hard to be consistent year in and year out. So you understand that. And I also understand that with Austin, he’s going to put everything he can into it. He’s always going to be committed.”

He was encouraged by the journey Riley took to get here: That the organization had seen him struggle, adjust and ultimately succeed was valuable. And it was something that some of them had believed in from the start—from the first daybreak on the earliest spring day.

“All we had to do was just build a foundation,” Washington says. “The rest that’s going on is just Austin Riley.”

More MLB coverage:

• Julio Rodríguez Is Here to Save the Mariners

• Inside the Drive: The Minor Leaguers Who Sprung a Union on MLB

• How the New Mets are (Mostly) Overcoming Decades of Dysfunction

• Everything in Aaron Judge’s Career Led Him to This Historic Season