Editors’ note: This story contains graphic accounts of gun violence.

Keegan Gregory loved his first high school diving practice so much that choosing a swimsuit for the next one took on outsized importance, like picking an outfit for the first day of school. This is what I’ll wear. This is who I’ll be. He stuffed all three of his Speedos into his backpack, along with his laptop and school supplies and a winter coat he borrowed from his mom, and decided he would choose a swimsuit before practice later. Later never came.

Keegan had stopped in a bathroom to pee before biology class when he heard gunshots. He opened the bathroom door slightly, to see what was happening outside, and saw students running through the halls. He quickly closed the door and at 12:52 p.m. he texted his family:

HELP

GUM SHOTS

GUN

IM HIDING IN THE BATHROOM

OMG

HELP

MOM

Keegan had just turned 15. He was 5’4″ and 105 pounds. A freshman. He thought he was alone in the bathroom, but when he turned he saw another boy.

Keegan did not know the boy’s name but he recognized him. He was a senior named Justin Shilling. A few months earlier, Keegan had seen Justin at a freshman orientation called Link Day. He was sitting in front of Keegan with a fanny pack full of Smarties, throwing them out to other kids.

In the bathroom, Justin pointed for Keegan to go into the lone stall. He told Keegan to sit on the toilet, with his feet up on the seat, so nobody would see he was there. Justin tried to hide behind the partition. He told Keegan that as soon as they had a chance, they would run.

They heard another gunshot. This one was so loud, Keegan thought it must have come from the girls’ bathroom, next door. It was actually in the hallway, and it left the school’s biggest football star, 16-year-old Tate Myre, dying on the floor.

Keegan and Justin heard the bathroom door open.

At 12:55, Keegan texted his family again:

he’s in the bathroom

Ethan Crumbley was once a boy in his mother’s arms, and then he was a quiet, troubled kid who played video games online and walked to school alone in ratty shoes—another American son left to his own devices until one of those devices was a gun. Now, police would later say, he had assumed the only role he would play in the town of Oxford, Mich., forever: the shooter.

The shooter had allegedly already shot 10 people, including fatal blows to Tate, 14-year-old Hana St. Juliana and 17-year-old Madisyn Baldwin. He kicked open the stall door and stared at Keegan and Justin.

Keegan looked back at the shooter. They had gone to Lakeville Elementary and now Oxford High together, but Keegan did not know who he was. The shooter was skinny, and when he spoke he mumbled. All of his authority came from the SIG Sauer SP 2022 9-mm semiautomatic handgun he held near his schoolmates. Keegan had never seen a real gun before. It would be months before he would stop seeing this one.

At 12:56, Keegan texted his parents:

i’m with one other person

he saw us

and we are just standing here

He thought about texting his parents that he loved them, but that felt too much like goodbye.

The shooter backed out of the stall.

Justin and Keegan were not sure what to do. Maybe the shooter had spared them and Keegan could pick up his backpack near the sink and go back to the diving team and the rest of his freshman year; and Justin could walk out with him, finish his final high school bowling season and go to his senior prom, graduate and head off to Oakland University to study business …

Justin opened the camera app on his iPhone and held it near the floor, at an angle. He motioned for Keegan, who was still crouched on the toilet, to look at the phone and see whether the shooter was still in the bathroom. Keegan quietly told Justin he could not see the screen.

Justin leaned over and looked at his phone. He saw a pair of feet. The shooter walked back to the stall and motioned for Justin to come out. At 12:59, Keegan texted his family:

he killed him

OMFG

The shooter turned to Keegan, pointed to the wall and told him to lean up against it.

Meghan Gregory missed the text messages from her oldest child because she was busy protecting her youngest one. The FDA had just approved COVID-19 vaccinations for kids under 12, which meant that her 8-year-old son, Sawyer, was eligible.

Meghan had seen the virus take an aunt of her husband, Chad; one of her distant cousins; and the parents of a few friends—and so she and Chad had been extremely cautious with their five children. Even after Oxford reopened its schools in August 2020, following the first wave of the pandemic, the Gregorys kept their kids home for remote learning all year. No one in the family had gotten the virus.

Now, as Meghan and Sawyer left the pharmacy at Target, fire alarms went off. Meghan would never know why. She looked at her phone, saw Keegan’s texts, jumped in her car and raced toward Oxford High, like hundreds of other parents. Sawyer asked his mom why she was sobbing. He thought about the fire alarms and wondered: “Did Target burn down?” Meghan had no answer for that, or for anything else. She was so rattled that she missed her exit on the highway. She got off at the next one, turned around and saw a fleet of police cars speeding toward her son’s high school.

Chad Gregory was in a meeting at his office in downtown Detroit when Keegan’s texts came in. He responded to his son right away, repeating the only advice he could think to give:

Just stay down

We can’t come to you but just stay down, quiet and calm

Stay down and don’t move or engage. We love you

Chad, who works in event hospitality, told the two colleagues in his meeting that he had to go. He bolted for his car in the parking structure across the street … 41 miles away from home. He and Meghan had chosen to raise their kids in Oxford, instead of the suburbs closer to Detroit, for serenity. They lived in a house on a lake. They went out on their pontoon to catch bass and pike, and they sat on the deck and watched meteor showers. They let their kids walk to two nearby parks without an adult—as long as they asked for permission first. Chad had turned down jobs in other cities so they could stay there.

Oxford, Meghan liked to say, was the safest place they could be.

At home, Sawyer Gregory looked out a front window at a suddenly terrifying world. A neighbor had lain on the floor in the fetal position, bawling. Something had gone tragically wrong, and if the adults couldn’t process it, what chance did an 8-year-old have? Chad arrived, glared at the neighbor, picked up Sawyer, put him on a bathroom counter and said: “Listen. Keegan’s O.K. Everybody’s just upset. We’re safe. You’re gonna be O.K.”

Keegan had texted his family to let them know he had survived. But when he came home that afternoon, his parents looked into his eyes and still didn’t see him. Meghan says her boy was “an empty shell.” Chad says he was “stone. Absolute stone. There was no emotion.”

They all walked downstairs to Keegan’s bedroom, where he started crying. He told them about the other boy who had looked out for him and was then killed in front of him, and about how the shooter pointed for Keegan to lean up against the bathroom wall. Keegan had believed he faced two options: He could follow the shooter’s instructions and get killed. Or he could run and get killed.

He had decided that if he ran, at least they would know he tried. He bolted past Justin, past the backpack with the Speedos in it, out the door and down the hall, past a teacher performing CPR on a kid—who turned out to be Tate Myre—running so fast and so frenetically that his arms flailed, his body an emergency helicopter desperately trying to take off. He ran and screamed and turned a corner and ran through the cafeteria, past the performing arts center and then to the school’s front door.

That’s where he first saw a police officer.

Keegan held his chest as he talked to the cop and pointed back down the hallway he had just left. The officer told him to go outside. Keegan paced back and forth and sat down on a curb by the snow.

Oxford’s dean of students, Nicholas Ejak, came out and walked Keegan back into the building. The shooter had been apprehended, but Keegan did not know that. Many students were still in the school. Keegan was still holding his chest. He remembered that the assistant principal’s office had a door that automatically locks when closed, so he went inside. Another administrator gave him a bottle of water. Police kept Keegan in the school for more than two hours before finally allowing him to go home.

That night, Oakland County Undersheriff Michael McCabe announced that “Police arrested the suspect five minutes after the first call,” which he said came in at 12:51 p.m.

If Keegan was sure of anything in those first uncertain days, it was that his community needed him.

Oxford vowed to do what American towns are supposed to do when a local teen kills his classmates. It would be #OxfordStrong. Keegan wanted to be strong, too. He got moving, moving, moving. He and his friends tied ribbons of blue and gold, their school colors, onto flag posts. They helped make T-shirts. Keegan slept at friends’ houses, or they slept at his.

Two days after the shooting, a student at nearby Lake Orion High was arrested for threatening to shoot up his school if he got a gun. One day after that, Keegan, Meghan and Chad attended a vigil downtown where somebody collapsed. It was just a fainting episode, but the citizenry panicked, fearing another attack. The shooter’s parents, it had been reported, were on the lam—had they come back and started shooting?

Locals came together for a vigil three days after the shooting—but the gathering rattled Keegan, who imagined gunshots in the crowd.

Scott Olson/Getty Images

The people of Oxford sprinted in all directions. Meghan says she saw a friend lift a double stroller with kids in it over his head and start running. Keegan lost a shoe. Meghan ducked into a restaurant owned by friends, which set Keegan off: How can you go inside? He was worried about being trapped in a crowded room with another shooter, but he and Chad followed Meghan inside.

Keegan thought he heard a gunshot.

Pop.

Then another, and another …

Pop pop pop pop pop-pop-pop-pop-pop—

“Do you hear them?” Keegan asked his mom. “Do you hear the gunshots?”

Meghan looked at him and said, “There are no gunshots, bud.”

Twenty-two years after Columbine, nine years after Sandy Hook, three and a half years after Parkland and 175 days before Uvalde, the Oxford shooter pinned his town on America’s map of shame.

Hana, Madisyn, Tate, Justin. What do you say to a family that loses a child, or to a town that loses four? “My heart goes out to the families enduring the unimaginable grief of losing a loved one,” President Joe Biden said hours later from Minnesota, where he was touting a bipartisan infrastructure bill. Keegan’s diving coach, John Pearson, says he received more than 500 cards from people in the diving community.

Hana, Madisyn, Tate, Justin. Their deaths dominated the national news, but by the crude, inhumane measurement of body count, the tragedy was not large enough to hold America’s attention for very long. Gun violence is now the leading cause of death for children in the United States. A 2018 Pew research poll found that most teenagers worry about a shooting at their school. A generation of students has been conditioned to believe the unbelievable: that school shootings are the cost of doing business in America.

Hana, Madisyn, Tate, Justin. In death, as in life, most people were drawn to Tate. He was the school football star, the kid who managed to be popular while still being nice to everyone. One of Keegan’s teammates, swimmer Kamari Kendrick, a sophomore at the time, told The Washington Post that Tate Myre was his “idol” and said “everybody knew him and everybody loved him.”

Days after the shooting, an Oxford football and wrestling coach, Ross Wingert, told the Detroit Free Press that Myre had tried to stop the massacre: “I was told that everybody in that school was running one way, and Tate was running the other way.” At the Big Ten championship game, four days after the shooting, Michigan’s football players wore patches with four stars, for the victims, plus the number 42, for Tate. A Change.org petition to rename Oxford High’s football stadium after Tate Myre said he had been “killed in an attempt to disarm the shooter” and that “his act of bravery should be remembered forever.” More than 300,000 people signed the petition.

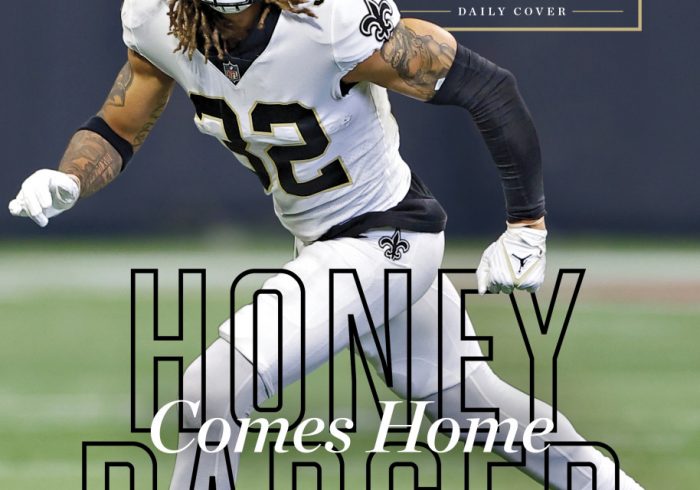

Among the deceased: a beloved football star. In the aftermath, stories spread about what happened to Myre on the day of the shooting.

Emily Elconin/Getty Images

Hana, Madisyn, Tate, Justin … and nearly Keegan, too. But he had survived, and so he did what Oxford survivors did. He went to their funerals. At Hana’s, he looked around and wondered: If something were to happen here, how do I get away? At Justin’s, he saw the casket from a distance, exclaimed, “It’s open!” and sprinted away. Keegan eventually made it through the funeral, and at the end he asked his parents whether he could go up to Justin’s casket by himself.

“I just want to talk to him one more time,” he said.

That day Keegan signed the guestbook with a teen’s penmanship, a freshman’s grammar and all the appreciation in his heart:

Thank you Justin. If it weren’t for you, I wouldn’t be standing right now. I can’t thank you enough. I pray and pray your doing good up there + I’m sorry.

Keegan walked out of that funeral to a life he had no chance of resuming. Forget dreams; the Gregorys couldn’t even make plans. For Christmas break, Meghan and Chad decided to drive the kids to Nashville, go to a Titans game, then surprise them with a trip to Saint Martin. But Keegan heard fireworks at the Titans game and panicked; and he saw cops in the stadium with guns in their holsters and worried somebody would steal one. The family left shortly after the opening kickoff.

In their Nashville hotel Keegan saw a man bleeding and had flashbacks to the school bathroom. He had a nightmare in which the shooter came into their room and killed his siblings, and Keegan was just standing there, unable to save them. He told his parents he did not want to fly to Saint Martin, because if something happened on the plane, he had no way out.

The Gregorys canceled their trip and went skiing in Northern Michigan instead. Keegan tried a jump, a ski fell off and he cut his right leg down to the bone. In the hospital, he gestured toward the front desk and asked his mom, “Did you see that? He looked just like Justin.”

Meghan looked. There was nobody there.

Justin was gone. In a way, so was Keegan. He told his dad he saw the SIG Sauer SP everywhere. At night, while the rest of the family slept, Keegan lay awake in bed, covered in fear. Every creak of the floor could be an intruder, every hour could bring death. As the oldest child, Keegan had the coolest room, on the lower level, with sliding doors that opened out toward the lake. One night, he had a nightmare where somebody pulled up on a boat and started shooting bullets through his windows. He tried to soothe himself with music, but when he put on headphones he thought: Well, now I can’t hear if something happens. He took the headphones off and stayed in bed, alone, until morning rescued him from the night.

When he got out of bed, Keegan was too exhausted to do anything but sit on the couch. He still wanted to sleep, but he couldn’t. He needed to keep his brain active, but he wasn’t sure how. He started cuddling on the couch with his mother, watching movies and shows he’d enjoyed as a little boy, like The Lorax and Yogi Bear. At one point he went to the bathroom, and while he was away fireworks went off on the TV. Keegan darted out, terrified, even though he said he knew it was just a show.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” he told his dad.

What was wrong was that he’d witnessed a murder on his way to biology class, and now his amygdala—the part of the brain that processes fear and trauma—was swelling. If something burned on the stove, Keegan freaked. Any sudden sound triggered him, and a house with two parents and five kids and a dog is an arena full of sudden sounds.

Meghan and Chad (far right) raised Keegan and their other kids in Oxford—it was, they believed, the safest place they could be.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

The Gregorys were living on tiptoe. They adopted a second dog to keep Keegan company at night. Meghan, who usually does the grocery shopping for the family, simply stopped doing it. Chad took over and wondered whether Meghan even noticed that food kept appearing in their kitchen. It didn’t matter to Keegan. He had no appetite. He was living on a bowl of cereal a day. In the middle of it all, Chad’s boss called. “I know it’s a rough time,” he said, but he had some good news: Chad was being promoted. Chad thought back to a world where that was a big deal. The whole family was trying to cope with Keegan’s trauma, and nobody was quite sure how to do it.

Keegan tried going to church, but his thoughts kept interrupting his prayers. Where were the exits? How would he flee from an attack? One night when Meghan came home, Keegan heard the front door open, so he ran out the sliding door of his lake-facing room and from outside called his parents on his phone: “I escaped out of the house! Someone’s in there! I’m in the neighbor’s yard!”

With no prompting or immediate context, Keegan would tell his parents the percentage of it happening in a grocery store or on a plane. He didn’t have to say what it was. He spent his nights researching shootings. He was statistically unlikely to be trapped in a bathroom at school with a shooter, but it had happened. Therefore, in his mind, anything that was statistically unlikely would probably happen. The kid who used to bounce giddily from one friend’s house to another’s had nowhere to go, because wherever he went he was doomed.

Prosecutors, police and local news outlets started to release details about the shooting, and most of it made other people look awful.

Police said the shooter’s parents had bought him the gun on Black Friday. Prosecutors implied that the school was culpable: A teacher, they said, had spotted the shooter searching online for ammunition, then called his parents. Afterward, the shooter’s mom texted him: LOL I’m not mad at you. You have to learn not to get caught. Ejak, the dean, and school counselor Shawn Hopkins had met with the shooter the morning of the attacks, after a teacher found a picture he’d drawn of a person who appeared to have been shot, along with the words, “The thoughts won’t stop. Help me.” Ejak and Hopkins had advised the shooter’s parents to seek psychiatric help—but they had not checked his backpack. If they had checked, prosecutors would say in court, they would have found the SIG Sauer SP, along with a hardbound black journal with the shooter’s name written on top of it and a vow inside:

I will cause the biggest school shooting in Michigan’s history

I will kill everyone I f— ing see

Days after the shooting, the district declined an offer from Michigan attorney general Dana Nessel to investigate, choosing to hire an outside law firm instead. A lot of strong people in a strong town in the strongest country in the world were getting suspicious.

The Gregorys say they kept contacting the school district to figure out a plan for Keegan to resume his education. Chad says that when he called, “the answer was always, ‘Just let us know what you need.’ We’re saying, ‘We don’t know what the options are.’ I don’t think they knew, either.” He says that when Meghan emailed administrators, “we were ghosted—not even responses. … We’re getting no email that says, ‘Here’s the counselor. Here are options for a revised curriculum.’ ”

School reopened 55 days after the Oxford shooting—but Keegan was at home, where his family says he was offered little guidance in terms of reintegration.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Oxford High reopened for business on Jan. 24—almost eight weeks after the shooting. The day before, Principal Steven Wolf posted a three-minute-and-41-second-long video telling “Wildcat Nation” that “we have been through so much to get to this moment” and that “we are reclaiming our high school.” “We have been reminded again and again,” Wolf said, “of one important fact: Our community is strong.” The first day back would be “a great day to be a Wildcat, and that’s because we’re #OxfordStrong.”

Four words Wolf did not utter: Hana, Madisyn, Tate, Justin. The school closed off the bathroom where Justin was killed. A temporary memorial for the victims was taken down before school started; the surviving children were told that this was so they could heal. Three days after school reopened, the families of Tate, Justin and Keegan, plus two more students, sued the shooter’s parents and the school district, arguing that administrators had ample reason to know the shooter was a threat and had failed to act.

Chad sensed a change in town. The victims’ families were asking questions: What did the district know? Why wasn’t there a transparent, independent review of the school’s protocols? Some other parents did not want answers—their kids were back in school, and they didn’t want to relive the day of the shooting. Others spread ridiculous stories. Parents told Meghan and Chad that they’d heard there were actually three kids in the bathroom when the shooter walked in. Or that Keegan was in there, Justin came in, and the shooter asked who wanted to die first. “Everyone,” Chad says, “had their own version of their own truth.”

After the victims’ families sued the school district, Wolf finally responded to the Gregorys’ emails. “I’m sorry I’m just replying this evening,” he wrote on Jan. 30. “I’ve spent most of today just going through emails trying to get caught up. Your request is important.” The principal offered Keegan the option of in-person, Zoom or online classes.

Keegan started to take the online classes, but even those were more than he could handle. He stopped after less than a month. He was wading through the shrapnel of his old existence, searching for his new one.

Jokes that were funny to him before were not funny anymore. Before the shooting, he loved anime—but now it was too gory. Art, in general, felt too free-flowing. Keegan needed control. He stopped fishing, which depends too much on the whims of the fish, and started playing ukulele. If I play these chords in this order, this song comes out.

His mind was a book that alternated between narrators: one first-person, one omniscient. The omniscient narrator understood that he was a 15-year-old kid who had seen what no child should ever see, and that it had traumatized him. The first-person narrator was irrational and short-tempered.

Meghan and Chad would lay out a schedule for the next day, and pragmatic Keegan would agree to it. Then morning would come and he’d snap: “I never said I would do that!” He raged at any surprise, no matter how trivial. “You told me you were buying Minute brown rice!” he screamed when the wrong brand showed up in the kitchen. He was learning to drive, but he’d lost his ability to stay calm and concentrate. He would pull into traffic without looking; his parents would say, “Keegan!;” and he would yell, “I didn’t see them!”

The rest of the family watched Keegan try to hold off his anger, to react like the boy he used to be. Then he would lose the battle with his new self and explode.

In the days and months after the shooting, #OxfordStrong would come to mean different things to different people.

Jeff Kowalsky/AFP/Getty Images

The Gregorys had fended off COVID-19, but Keegan’s trauma spread through the family like a contagious disease. Sawyer told his mom, “I’m never going to Target again.” Bentley, then in fourth grade, who always wanted to be Keegan, defended his brother’s explosions: “Remember, his brain isn’t working right.” Piper, an eighth-grader, made herself busy so she wouldn’t have to deal with it all. Peyton, a seventh-grader and the middle child, called her house from school in the middle of the day, worried about her big brother: “Is Keegan up? Is he O.K.?” Sometimes she asked to stay home. She would miss 27 days of school and her grades plummeted—a crisis dwarfed by a much larger one.

Meghan, who was coaching gymnastics six or seven days a week, took what she thought was a temporary break, but eventually she closed her gym. She started making her kids wear tennis shoes everywhere, so that if anything happened they could run. She heard other parents talk about how brave their kids were for going back to school, and she wondered: Do they mean that Keegan is somehow less brave because he stayed home?

Meghan and Chad tried to make sense of the new Keegan. Crowds scared him. School scared him. Would diving scare him?

Diving practice was after school, with fewer kids. His team sometimes practiced at another campus, nearby Lake Orion High, because Pearson, the coach, led both teams, and so Keegan decided to attend a workout at Lake Orion. Pearson could tell Keegan was nervous. Pearson usually stands while he coaches, but he sat on a bulkhead and had Keegan sit in a chair next to him, a small but welcome act of tenderness.

Pools can be loud—boards bouncing, words echoing off walls—but diving itself gave Keegan the control he craved. If he had played a free-flowing sport like hockey or basketball, he would not have gone back. But dives are scripted and independent: stand, jump, flip, enter the water, swim to the edge of the pool.

Diving gave Keegan bits of what he needed: “You’re all hyping each other up, even though we’re against each other,” he says. “I love the community.”

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Keegan’s first meet was on a snowy day in Berkley, a Detroit suburb. Beforehand, he sat on the bus with his headphones on, staring at the Waze app on his phone. The ride strayed from the route, and Keegan called his mom in a panic: “The bus is going the wrong way!” The driver had just taken a wrong turn, but that was the last time Keegan took the bus.

He started to find that he could enjoy diving meets as long as he sat on the side by himself, wearing noise-canceling headphones, when it got too loud. Then diving started to give him bits of what he needed: “You’re all hyping each other up, even though we’re against each other,” he says. “I love the community.” The sport even got him to walk back into Oxford High for a few practices. He entered through an emergency-exit door right behind the diving boards, never seeing the rest of the school.

Keegan made it all the way to Michigan’s state championships, where he finished 23rd in the boys’ one-meter, quite an achievement for any freshman, let alone a severely traumatized one who was barely sleeping.

Watch him on that board, and you might think Keegan Gregory was himself again. His coach knew better. On inward dives—when athletes start by facing away from the pool—Keegan used to jump up and spin within two feet of the board, as he was supposed to do. After the shooting, he jumped five or six feet away from the board, his mind pushing his body toward safety.

In March, Keegan went back to school during the day—for one class, with only a few students in it. He says it was O.K., because “I knew every single person since, like, kindergarten.” He got there late, left early, survived it all and decided he wouldn’t be doing that again.

In April, a terrorist threat was made against three nearby high schools—including Lake Orion, where Keegan practiced diving. A teenager in the United Kingdom was arrested for what was apparently a sick joke. Keegan became even more steadfast: He was never going back to school.

In May, the office of Oakland County Sheriff Michael Bouchard awarded valor citations to two deputies for responding to the Oxford High shooting “without hesitation,” for entering the high school “without waiting for additional backup” and for apprehending the suspect “within seconds.”

“Your actions, while risking your own safety,” Bouchard said, “were why the senseless shooting stopped. Had it not been for the two of you, the shooter probably would have exhausted his last 18 rounds. The students, faculty, their families and the community are forever indebted to you both.”

The sheriff was telling the world his officers were heroes. Parents were suing the school district. The district was shielding itself with lawyers. The shooter had pleaded not guilty to four counts of murder. Prosecutors charged the shooter’s parents, James and Jennifer Crumbley, with involuntary manslaughter; they also pleaded not guilty. Hana’s sister, Reina, was pushing the school to erect a permanent memorial to the victims (without success). Keegan was seeing two therapists.

One therapist was conventional; the other specialized in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, a method that helps patients process trauma. The EMDR therapist told Keegan’s parents that he was starting to disassociate from reality—disconnecting from his own thoughts and memories. (He knows it, too. For this story, Keegan said that if his parents remembered something and he didn’t, it’s fair to say that it happened.) Part of that EMDR therapy meant closing his eyes and reliving the day of the shooting, until he hit what his therapist calls a “point of disturbance” and what Keegan describes as “all of a sudden, in my stomach, an anxiety feeling … boom.” He closed his eyes and saw the shooter kick open the stall door, saw blood all over the bathroom, saw Justin’s face as he lay dying at age 17…

“I hate therapy!” he told his parents.

They asked whether he wanted to quit.

“No,” he said. “I know it’s going to make me better.”

Keegan knew he needed therapy to have any chance of getting from here to there—of forming a social life when he was scared of crowds; of going to college if he never went back to high school; of being the big brother that his siblings missed. But it all seemed so far off. He was downing Tums like they were popcorn, 20 to 30 tablets a day, just to survive 24 hours in Oxford.

He told his parents he wanted to start working out. They took him to Planet Fitness, but he dismissed it as “a soccer mom gym.” Keegan wanted to add real strength. He started going to Building Your Temple Fitness, in town, where serious weightlifters went.

In June, Keegan went to visit his mom’s family in Ohio, and he felt freer than he had since he fled the bathroom. Then he came back home, and anxiety choked him again.

“I hate Oxford!” he told his parents.

He used to feel so free in his town. Now he felt trapped in it. His parents were getting increasingly frustrated with what they felt was obfuscation from the district and with the portion of the community that they thought was lying to itself.

Keegan says he likes the discipline and purpose lifting gives him. His parents see something else: new armor.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

County prosecutors, along with the lawyer for the victims’ families, produced what they say were a slew of warnings that the shooter would become the shooter. On a math worksheet he drew pictures of people being gunned down and wrote, “My life is useless,” “Blood everywhere” and “The thoughts won’t stop, help me.” He had gone to school with a baby bird’s head kept in a jar. But some people rushed to defend the district. (Attorney Timothy Mullins, who represents the district, did not respond to repeated interview requests for this story.)

The Gregorys felt their truth was being dismissed—and their son marginalized—because people didn’t want to know what had really happened. By Michigan law, Keegan wasn’t even technically a victim.

At a meeting with Michigan’s attorney general, Meghan asked why the proper timeline hadn’t been released. She had the text messages. She knew there was no way the cops came in and arrested the shooter within five minutes, because Keegan was still trapped in the bathroom with him after that. Another parent told her she had it all wrong—they had personally checked with the sheriff and confirmed that the sheriff’s timeline was correct.

Meghan started asking Chad, Can we move?

“But I don’t mean move to another state,” she says. “I mean move to another country. It’s not like you can move to Colorado and you’re not going to have [this] happen.”

Chad says he remembers watching news coverage of the Columbine High shooting, in the spring of 1999, and how it was all about the police—“whatever they did or did not do to save lives”—and the victims, and the shooters. He says: “Personally, I don’t f—ing want to know about the shooters, right? How does this get stopped? Where’s the bold sort of overarching authority that comes in and says, ‘This is not acceptable?’”

School shootings are clearly not acceptable, yet they are just as clearly accepted. CNN found that in one stretch covering 2009 to ’18, there were 288 school shootings in the U.S. In that same time, Canada, France, Germany, Italy and the U.K. combined for five. So much has changed about American life since then, but not that. According to the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School for Homeland Defense and Security, 110 children have been shot to death on school grounds in the last two academic years. Another 287 were wounded, and 39 suffered minor injuries.

Those are facts. So is this: America has more guns than adults—by far the highest rate of civilian gun ownership in the world. Connect those two facts, and you are accused of playing politics, of having an agenda, of being anti-American, even when you are trying to protect children, even when the child is your own son.

The sadness in Oxford runs so deep and so wide that a lot of people prefer to look away. Chad understands. He is embarrassed to admit this, but it’s true: By the time Sandy Hook happened, in 2012, he had already stopped watching news about school shootings. It wasn’t that he didn’t care. He cared so much that caring overwhelmed him, and so he took steps to care less. He had been desensitized by choice.

Meghan watched for days. Even after a shooting took four of her town’s children and wrecked the life of her own, Meghan searched inside herself, looking for empathy for the shooter and his parents. She has none anymore. She copes by accumulating facts about the case, and Chad worries she is stifling her emotions.

Chad walls off, and Meghan worries he is being avoidant. He still can’t look at Keegan’s text messages from the bathroom. But they need to give each other the space to cope in their own ways or their marriage will crack. They get up every day determined to be supportive spouses, good parents and thoughtful citizens of an angry nation.

The diver sought control, and not just over a sport. Keegan started waking up early, working out five or six days a week and monitoring everything he put in his body. He cooked lean, protein-rich meals for himself and drank protein water. In the Gregorys’ kitchen this summer, Meghan casually mentioned that when Chad travels for work she stays up late and sleeps late. Keegan sternly told her to take melatonin at 10 p.m. and put her phone away. Then he made himself a meal of ground turkey and rice. He will never get to be a typical teenager, so he has stopped trying.

“Most people my age will stay up till 3, sleep until 1 and do nothing,” he says. “But I feel good about myself when I get up, I go to the gym, I eat good foods.”

Keegan has the speech patterns of somebody who was thrown from childhood into adulthood in less than an hour, dropping “whereas” and “body dysmorphia” into conversation but describing the diving community as “the funnest thing ever.” This summer, he still couldn’t fathom going back to school, but he had started making other plans. He intends to compete in a powerlifting competition in Ohio in November, part of a five-year plan to become a bodybuilder. He says he likes the discipline and purpose it gives him.

His parents see something else: Nobody else would protect Keegan, so he started adding layers of armor to protect himself.

Away from school, Keegan still made it all the way to state, where he finished 23rd in the one-meter.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

The Oxford school district maintains that it did all it could reasonably be expected to do. The shooter’s parents say the media and prosecutors have unfairly held them responsible for the shootings. The sheriff’s office says the shooter was arrested within five minutes of the first call for help, but the time stamps on Keegan’s text messages say otherwise.

Thousands of people were understandably touched by the story of a beloved high school football star dying while trying to stop a shooter. There is no doubt that Tate Myre was beloved. But there is no indication he was trying to stop the shooter. The Myres’ lawyer acknowledges that Tate was shot from behind, from a considerable distance. What kind of society needs a dead teenager to be a superhero? Does that mean the kids who fled were selfish for trying to save their own lives? Why isn’t being a great kid enough?

As for the sheriff who commended his officers for stopping the shooter before he exhausted his last 18 rounds: The truth is that after Keegan ran out of the bathroom, the shooter walked out on his own and did not fire another shot. He got on his knees and surrendered, and then police found and arrested him. It’s all on the security footage. Meghan and Chad have watched it.

The stories we tell ourselves rarely include the shooter stopping on his own. But that is what happened in Oxford. “He was done,” Chad says. Why? Maybe Keegan’s sprint surprised the shooter and jolted him out of his murderous trance. Maybe he was already coming out of it when he entered the restroom, and that’s why he took several minutes to execute Justin. Maybe we will never really know. Maybe you don’t want to hear any more about the shooter.

But maybe you do care that in July, when Meghan, Chad and the victims’ families’ lawyer watched the video footage from the day of the shootings, they saw what appeared to be a security officer open the bathroom door while Justin, Keegan and the shooter were inside. The officer then closed the door and walked away. When the lawyer went public with it, the school board’s response was not outrage or remorse; it was self-defense.

School board president Tom Donnelly, a pastor at Firmly Rooted Ministries, responded immediately in an email to the community, writing that “isolating a single moment in a video—out of context—does a disservice to our staff members. … These attempts to sway public opinion with speculation before the investigations are complete are counterproductive and designed to divide us.”

At an Oxford school board meeting two days later, Meghan spoke.

“I am here trying to understand tonight how we got to this point,” she said. “We have always trusted Oxford schools with our children. … I’m trying to understand, as patient and quiet as we have been, why you have chosen to turn this personal. How unprofessional to try to place blame on us for the community divide.”

She got a standing ovation.

Oxford was broken.

“People can’t listen to each other right now,” says Pearson, the diving coach, who skipped the school board meeting because he loves the Gregorys but is sympathetic to the school board. “They can’t talk to each other because of the emotion. It’s torn the community apart.”

The Gregory family walks on both sides of that divide. Their lawyer is slamming the school district, but four of their kids keep going to district schools. They shop among those who don’t understand them, and they commiserate with friends who do. They have decided to stay in Oxford for now, because at least in Oxford the shooting does not have to be explained. In packs people argue, but one on one they get it.

Then there is Keegan. In August, he sat on his back deck wearing an OXFORD SWIM AND DIVE T-shirt and a camouflage Detroit Tigers hat, with the sun and lake behind him and a bottle of protein water in front of him. He plans to dive again this winter, but he has built his life more around the gym and health food, isolating himself as a survival mechanism. He wants to hang with people, but not in crowds. He doesn’t want to go back to school, but he wants to want to go.

“I could go in for one class,” he said. “And I think I’m gonna start doing that and see how I feel. Because, to be honest, I have no idea how I’m gonna feel when I’m actually in the school. Because I could think that I’m gonna be fine—and then it’s horrible. Or I could think that it would be kind of bad—and then I’m fine.”

Yellow school buses line up on Oxford Road. The sun has yawned itself awake. Another school year has begun. Kids stand outside Oxford High on August 25, carrying the clear plastic backpacks they were given after the shooting, waiting to go through their school’s newly installed metal detectors—seniors and freshmen, athletes and artists, best friends and future romantic partners … and standing in line with them: a sophomore named Keegan Gregory.

He has decided the best way he can beat anxiety is to stare it in the eye until it blinks. His schedule is stacked with morning classes. He says he will “knock out those” and then go home before lunch. His parents were skeptical right up until this morning, when Keegan got up early, listened to music, took an anti-anxiety medication called buspirone and found the courage to walk into the building where the shooter wrecked his life.

“He was like a ghost—I’d never heard of him, I’d never seen him, not even in the halls,” Keegan says of the shooter at one point. “I’d never seen that face. So there’s also that side thought: How do we know there’s not someone else I don’t know about in school who could be a bit crazy?”

He convinces himself that the metal detectors, the clear backpacks and the ID checks will protect him, and he points out that “the majority of the time, I’ll be in a classroom, which will be good. Nobody in a classroom really got injured.” Since the day of the shooting, he has grown from 105 pounds to 138, and most of that new weight is muscle. He is #OxfordStrong.

He also has a new tattoo on his right forearm. His mom and dad got the same one: the date of the shooting, in Roman numerals, with four hearts at the bottom. The first three hearts are for Hana, Madisyn and Tate. The fourth, for Justin, has a halo over it.

Meghan, Keegan and Chad each got inked to remember the shooting, with a special nod to Justin.

Courtesy of the Gregorys

Keegan walks into school. He does not know that his mom is sitting in the parking lot, in her Kia Carnival, with the engine running, in case he texts and says he wants to go home.

The front door of the Kia opens and Jill Soave, Justin Shilling’s mother, climbs inside. She and Meghan did not know each other before the shooting, but now they’re close friends. They went back into Oxford High in January, before it reopened, and prayed together. In May, the Shilling family joined the Gregorys and the Myres in suing the district. Jill does not resent Meghan because her child got out, and Meghan does not feel guilty for it.

Jill places a white to-go cup of Bigelow chamomile tea above the dashboard. She is wearing a pink shirt to honor Justin, and she is thinking about her youngest son, 14-year-old Clay, who is, like Keegan, a sophomore at Oxford. The last time Clay saw Justin alive was in school that morning; their paths crossed in the same place at the same time every day. When Clay went back to school last spring, he skipped a class so he wouldn’t have to go to that same spot. On many days since, he has gone into school, called his mom and said, “O.K., panic attack,” and she has picked him up and taken him home.

Clay “feels a sense of pride to not run from it,” Jill says. “But that doesn’t always last.”

The sun continues to rise. Other kids’ parents keep texting Meghan: We hear Keegan’s at school! There are signs that Meghan’s life is getting easier. Jill’s is getting harder. People want to move on, and she never will. She says that at a recent open forum for parents at Seymour Lake Park, one woman complained, “I don’t think it’s fair that the victims get to see the video [of the shooting] before us.” Jill says, “Desperate, needy people are drawn to these things.” Another parent said that she needed to know, for her own mental health, that the school did not intend to do anything wrong. Jill thought: If I can keep my composure and my kid is dead, and you can’t keep your composure … But where would arguing lead her? To bitterness? Anger? Who wins then?

“You become what you’re opposing,” Jill says.

Together, the mothers try not to let casual indignities rob them of their grace. They don’t have the time or energy for every fight. Jill says, “Certain days, I can’t leave the house. It’s hard to think and function.”

Jill looks out at the school where her son was killed, in the district she is suing, and she says, “If I had it in me, I’d volunteer in the lunchroom.”

Jill and Meghan keep looking through the windshield at their town. A Coca-Cola truck is parked next to the football stadium. Jill points to the apartment building across the street from the high school. In April, a single father and Army veteran named Dennis Kendrick was shot to death there by a man he had never met, in what police say was a case of mistaken identity. Just a few months after telling The Washington Post that Tate Myre was his idol, Kamari Kendrick had lost his dad, too. Jill says, “My heart just broke.” She donated $500 to the GoFundMe campaign for Kamari.

“Every time something happens, it’s always the same thing on the news: ‘This is just pure evil,’” Jill says. “It’s like a movie with the same script. I just don’t understand why so many people have so many guns.”

At 9:04 a.m., Keegan texts his mom:

I might try and do lunch

Meghan is stunned. Jill is so happy for her. Keegan ends up staying and eating lunch in a courtyard outside with his friends. When he goes home, he asks his mom to text his EMDR therapist, to let her know that he made it through the day and that he is grateful for her. Then he takes a long nap.

Keegan will go back to school the next day, and the next week, and he will go to Oxford football games with his friends, and he will keep going back to school until one early September day when he sees a fellow student in a trench coat and panics. He asks his mom to get him out of school safely. On Sept. 11, before he is ready to go back, Oxford High emails the community to say there has been a vague threat from an unknown person on Snapchat. The school remains open, but Keegan stays home. That week, two members of the Oxford school board resign, including Donnelly, the board chair. The following week, Keegan starts going back to school again.

Last year, on Nov. 30, Keegan Gregory went home from school and told his parents the story of the bathroom, the shooter and the other boy.

Justin was in the hospital, being kept on life support so that doctors could harvest his organs. But Meghan and Chad didn’t know that. All they heard was that the other boy’s name was Justin Shilling, and he was in the hospital, alive. They told Keegan.

Keegan did not believe them. They had not seen what he had seen. He knew.

But he wanted to believe.

He thought about Justin, the last person he met in his last moments as a child—how Justin told him to crouch on the toilet, so nobody could see him, and how Justin said that when they had a chance, they would run.

Keegan asked his parents a single, desperate question.

“Does he know I’m alive? He wanted me to live.”

Keegan is trying, Justin. He is trying so hard.

• Jeff Luhnow’s Next Act: Soccer

• All Eyes on Zion Williamson

• In the World of Phoenix High School Football, ‘S— Is Cutthtroat’