At first blush, anyway, it looked like some sort of social science experiment playing out in real time. If you were being pursued by a man nearly twice your weight and considerably taller, with designs of driving you into the ground like a smoker snubbing out a cigarette, would it be an exercise in fight? Or in flight? For Garo Yepremian, the answer was a frantic combination of both.

Yepremian, then 28, was the leading scorer for the Miami Dolphins, who were about to apply the final bit of applique to an undefeated 1972 season. It was late in Super Bowl VII, the Dolphins leading 14–0 with a little more than two minutes left, when Yepremian was summoned to try a 42-yard field goal.

Don Shula, the Dolphins’ stoic coach, was never accused of being a gooey sentimentalist, but he was taken by the symmetry of it all. As he later told reporters: “I thought, ‘Boy, this will be great if Garo kicks this field goal and we go ahead, 17–0, in a 17–0 season. What a great way that would be to remember the game.’ And then Garo did what he did.”

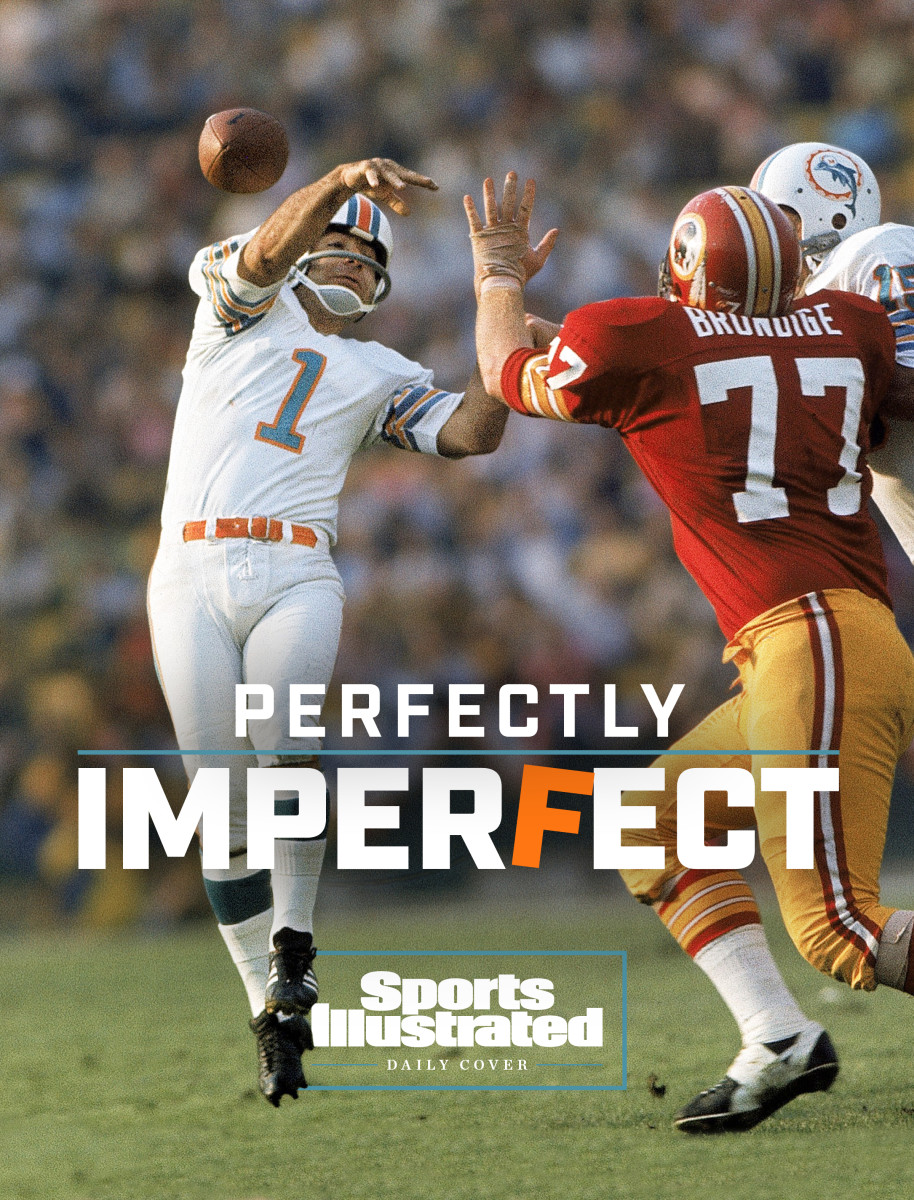

What did Garo do? It’s a challenge to describe. Fire up YouTube (header: Epic Super Bowl Fail), as tens of millions have, and you will see a sequence of football masquerading as vaudeville. After Yepremian’s kick was blocked by Washington’s 270-pound defensive tackle Bill Brundige, the ball caromed back to Yepremian’s right. Aggressively, he ran to the ball and grabbed it off the second bounce. Instead of going down, he began running.

It looked, for a second, as though he might try a dropkick, a nod to his past as a soccer player. Then, sensing the pursuit of upcoming players with violent intentions, Yepremian decided to throw. He resembled a man trying to throw a water balloon slathered in grease, the ball slipping from his grip and floating straight up, right above his head, his arms and legs moving in different directions. Next, Yepremian later explained, he attempted to bat the ball out of bounds; it ended up, however, in the hands of cornerback Mike Bass.

While Bass was running the ball back 49 yards for a most unlikely touchdown—a 10-point swing in the course of seconds, the first shutout in Super Bowl history thwarted—the play was already lodging into the public consciousness, a blooper doing the early-1970s equivalent of going viral. Imagine the Butt Fumble, not on Thanksgiving night, but in the waning moment of the biggest game of the season.

Part of it was the sheer comedy, the 5’7″ Yepremian being chased by these behemoths. His bald head, with compensatory mutton chops poking out from his helmet, only added to the—forgive the pun—fish-out-of-water visuals. But some of it was the context, an absurd gaffe with two minutes left in a Super Bowl, for a team trying to preserve an undefeated season.

When Yepremian slunk back to the sidelines, he didn’t have time to grab the single bar over his chin and remove his helmet. Shula was already in his face. Linebacker Nick Buoniconti sidled up to Yepremian and added, “We lose this game, I’ll kill you.” Yepremian later recalled, “I never prayed so much.”

There would be no acts of kicker-cide. Yepremian’s prayers were answered. The Dolphins hung on and won 14–7, preserving their historic undefeated season. But the kicker’s day had been ruined. What ought to have been a pinnacle moment of his career was, at best, bittersweet.

More relieved than exultant, he would leave the team’s Super Bowl party at the Beverly Hills Hilton and return to his hotel room. There, he took an ice bath, an attempt to cool off in multiple senses. Years later he told Miami columnist Greg Cote, “I honestly felt as if my life was over.”

There was an irony to it all. Here was one of the dynastic teams in NFL history, a collective that would achieve something no other team would replicate even a half century on, coming through an entire NFL season undefeated—a source of both pride and, famously, annual gloating celebration among the living members of the team. And yet, if you had to pick one single signature moment from that unblemished 1972 season, it might be Yepremian’s blunder.

Here’s another shattering irony: It’s hard to decouple the play from the otherness of the protagonist. That gaffe? It was committed by a foreigner playing a foreign sport, an immigrant—replete with that funny-sounding surname that barely fit on his jersey—who spoke accented English. And it obscured the fact that the tale of Garo Yepremian—patriot, veteran, entrepreneur, self-made success, unshakable optimist, devoted husband and father—makes for a classic Great American Success Story. That’s what ought to be in heavy YouTube rotation.

Hey, my brother can do that. So thought Krikor Yepremian as he watched his first American football game. Their parents fled the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian genocide during World War I and landed in Cyprus, the Eastern Mediterranean island nation between Greece and Turkey. Krikor and his two younger brothers grew up there; the Yepremians found work in the garment industry, but their existence was so meager that the family lacked plumbing and they burned olive pits for warmth.

In the 1960s, the Yepremians fled to England to escape Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus—all except Krikor, who headed to Indiana University to play soccer and study law. It was the mid-’60s, and Krikor, seeking to accelerate his assimilation in the U.S., attended a Hoosiers football game. Watching the field goal kicker try to cleave the uprights, Krikor thought of his younger brother Garo who moonlighted as a soccer player when he wasn’t working in a London warehouse.

Yepremian as a young man with his mother, Azadouhi, and father, Sarkis.

Courtesy of the Yepremian Family

Krikor made a few phone calls, and soon Garo, then 22, was headed to the United States to kick for Butler University in Indianapolis. One problem: Garo had already accepted payment as a member of a professional British soccer team, thereby forfeiting his NCAA eligibility. The school realized the issue and rescinded the scholarship offer, and the Yepremians didn’t have the funds to pay tuition. Marooned in Indianapolis, Garo practiced his field goal kicking on various high school fields, approaching the ball, planting his right foot, cocking his left foot and letting fly. Damn, if he couldn’t guide the ball between those metal poles that, to him, looked for all the world like a tuning fork.

Recognizing his brother’s talents, Krikor wrote letters to NFL teams informing them of Garo’s kicking prowess. Two teams, the Falcons and Lions, offered Garo a tryout. When Krikor, acting as agent, negotiated a superior offer from the Lions, the Yepremians moved to Michigan. Garo would kick in the NFL. Krikor would begin working in customer relations for an even bigger local institution, General Motors.

Garo Yepremian signed a contract Thursday, got his working papers on a Friday and, on Sunday, Oct. 16, 1966, played in the first NFL game he had ever witnessed. “I didn’t know a jock strap from a chin strap,” he said.

That was no exaggeration. Before the game, he watched his teammates in the locker room applying tape and figured he might as well join in. He began idly wrapping his arms and chest. Teammates had a laugh and then yanked off the tape. Though Yepremian was prematurely balding, he had a thick carpet of hair covering his chest. He later joked to a friend that the tape removal made for his most painful NFL injury.

Before that game against the Colts, Lions coach Harry Gilmer lamented that the team had lost the coin toss. Eager to please, Garo dropped to his knees and began pawing the ground in search of the misplaced token. After explaining that, no, it meant Yepremian would be kicking off, Gilmer then warned that opposing players were looking to divorce his head from his body. “So run back to the sidelines immediately after your foot makes contact with the ball.” Yepremian obeyed instructions but dashed off to the opposing sideline, all to the great amusement of both teams.

Still, Yepremian was a quick study. As a rookie, he broke an NFL record, kicking six field goals in one game. (Another day he was leveled by Packers fearsome linebacker Ray Nitschke, causing Yepremian to rethink his decision not to wear a bar on the facemask of his helmet, the last player ever to do so.) After converting an extra point that sealed a Lions win, Yepremian celebrated. When his burly teammate Alex Karras snarled, “What the hell are you celebrating for?” Yepremian beamed and declared, “I keek touchdown.”

After two seasons in Detroit, Yepremian was drafted into the U.S. Army. The Lions told Yepremian the team would keep his roster spot and he was free to return to England or Cyprus and spend a year outside the country. Yepremian declined, intent on, as he saw it, repaying an obligation to the country that welcomed him. “I want to be an American citizen,” he explained. “So I’m going to act like an American citizen.”

Yepremian had a background in soccer (left), and interrupted his NFL career to serve in the military (bottom row, far right).

Courtesy of Yepremian Family

Forfeiting his roster spot, he reported to basic training at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri. He lost 10 pounds in eight weeks and left as a squad leader. He then went to Fort Carson in Colorado to serve as a cook and spent 1969 in the Army Reserves. When Yepremian did his stint and returned, the new Lions coach, Joe Schmidt, told Yepremian that his kicking services were no longer needed. “I think soccer-style kicking is a fad,” Schmidt told him.

Crestfallen, Yepremian prepared for Career 2.0. He had no college degree and was rejected for a job working on the assembly line at the Ford plant. He made plans to open a silk tie business, carrying on a family tradition, as his father sold fabric in Cyprus and his mother had worked as a seamstress. Friends suggested he return to Cyprus or rejoin his family in England. “I feel too American,” he told them.

In 1970, Yepremian got another reprieve. He was summoned to Miami. There, a new coach, Shula, was attempting to reinvent himself after a mixed record in Baltimore that included losing Super Bowl III, the one in which Jets quarterback Joe Namath made good on his prediction. That summer, NFL players were either striking or locked out, depending on interpretation. Fearful of being called a “scab,” Yepremian would not accept lodging for the Dolphins. Though broke, he paid for his hotel during tryouts. That summer ended with the NFLPA becoming an official union and Yepremian making the Miami roster.

In Shula’s first season, the Dolphins improved from 3-10-1 to 10–4. And Miami’s new kicker figured significantly. Yepremian made 22 of his 29 attempted field goals over 13 games, and made all 33 of his extra-point attempts. He also met a University of Miami undergrad, Maritza Javian. Though she grew up in Philadelphia, she, too, lost family in the Armenian genocide. “It was like a premonition,” she recalls, “The Dolphins have an Armenian kicker? I better learn football.”

They were introduced by friends at an Armenian restaurant in Miami. She asked for an autograph. They dated the next day. By the end of the week they were engaged. Meanwhile Krikor joined his brother in South Florida, serving as an executive for the Miami Toros, a pro soccer team owned by Joe Robbie, who also owned the Dolphins.

Chastened by his treatment in Detroit, Yepremian started the equivalent of a side hustle, running a silk tie business when he wasn’t kicking field goals. He started it in the basement of his home, but business boomed and soon he had to rent space. The New York Times featured the business, noting: “On the football field this season, Garo Yepremian gained fame as a tie‐breaker. But in the basement of his Miami home, he turns into tie‐maker. Neckties, that is—wide, wild and woolly ones, with bright, abstract patterns that remind you of the kind of visions people must have on acid trips.”

The following season, he was the best kicker in the NFL; his 117 points led the league in 1971; he kicked the game-winning field goal to beat the Chiefs on Christmas Day, a dramatic end to what had been the longest game in league history. In that season’s Super Bowl, the Dolphins fell short against the Cowboys, 24–3, Yepremian’s field goal marking Miami’s only points.

The 1972 Dolphins were built in their coach’s image. They were not spectacular or outrageous. The roster was filled with Pro Bowl players, but devoid of a transcendent star, as the “No Name Defense” nickname suggested. They performed with steady, clinical efficiency and without a discernible weakness. Their “training facility,” such as it was, ranked among the shabbiest in the NFL, a reflection of Robbie, a notorious miser.

Yepremian, like most kickers, existed on the periphery. He laughed when teammates pranked Shula by putting a baby alligator in the coach’s personal shower. He walked around the locker room handing out ties. But his best friends in Miami were not his colleagues; they were members of the local Cypriot community or other parishioners at the Armenian Epistolic church. “We all liked Garo,” Jim Kiick, the late Dolphins running back, once said. “But he was the kind of guy to go home to his family.”

Maritza recalls that Yepremian would join his teammates’ nocturnal outings to be social but was never a drinker. “He’d take a sip of a vodka gimlet, take a sip and leave it on the table. After one and a half beers he’d start saying, ‘Isn’t life wonderful?’ And soon he’d fall asleep.”

It wasn’t just the players who outdrank Yepremian. Maritza tells the story of going to a team function at the Orange Bowl and finding a man, lifeless, his head on the table. “It looked like he died.” She told others in the room; her level of concern was not matched. “Don’t worry, it’s just Mr. Robbie,” she was told. “He’s drunk. He gets like that.”

Yepremian’s game-winning kick against the Chiefs earned him an SI cover.

Herb Scharfman/Sports Illustrated

The Dolphins slalomed through the 1972 season more than they rock-starred through it. They were revered, but there was no breathless national anticipation every time they played. There were blowouts, yes, thanks largely to a soft schedule. But also close calls, not least a game against the Vikings in which they trailed 14–6 before reeling off 10 straight fourth-quarter points. Even entering Super Bowl VII, the 16–0 Dolphins were the underdogs against Washington.

In that game, they were cruising to another win when right before the two-minute warning, the field goal unit trotted on. Had Yepremian simply missed the 42-yard field goal, it would have been an afterthought. Instead? Go back and listen to the television broadcasters and, as the play unfolds, they gasp and momentarily freeze as they process what has unfolded. “What a kooky play. Yepremian lost his head and tried to throw a pass. … he’s thinking now about a new tie pattern,” said Curt Gowdy. “I thought we saw it all when we saw Franco Harris!” added color commentator Al DeRogatis, a reference to the Immaculate Reception, which had occurred two weeks before.

How did Yepremian process it? He knew instinctively that he had a choice. He could either be bitter about what he called “a [blunder] everyone makes—mine just happened to occur on the biggest stage.” Or he could lean into it. He chose the latter. As reporters came by his locker after the game, he forced a smile. “This is the first time,” he said, “the goat of the game is in the winner’s locker room.”

In the offseason, he made jokes at his own expense. He considered making a silk tie that referenced the play. He went on talk shows and radio shows and revisited his moment of infamy. It helped that the Dolphins won the Super Bowl; this wasn’t quite football’s version of Bill Buckner in the 1986 World Series. Yepremian’s family also points out that, considering he didn’t play football before reaching the professional level, there were limits to how upset Garo could get over a sports mishap. More broadly, when your family has fled an ethnic cleansing in their home country, you know all too well that there are matters in life far more grave than a turnover. “He couldn’t live it down,” says Maritza, with a carefree laugh, “so he turned it into a joke.”

Still beneath the surface, he was haunted. “My dad was really competitive and really took being an athlete seriously,” says Garo Jr., now 48, a graphic designer in the Philadelphia suburbs. “He had fun with it. But I think he understood that it was a coping mechanism. He accepted it and didn’t run away from it. But it’s not like he was proud of it.”

His coach seemed to recognize this. A few weeks into the offseason, Yepremian went to the mailbox and found a typed note bearing Shula’s letterhead. It read, in part, “There is nothing that can be done about “that play,” but to learn from it and keep it from happening again. The important thing is to remember and be happy about it and all of the good things that have happened to you and the Dolphins … and relax and enjoy them. Sincerely, Don. F. Shula.”

But when training camp opened for the 1973 season, the Dolphins practiced a new drill on field goals. The holder, Earl Morrall, intentionally let the ball slip through his fingers. Shula yelled at Yepremian, “Fall on it! Fall on it!”

Miami kicked off the 1973 season with the team’s 18th consecutive win. The Dolphins then lost to the Raiders in Oakland, 12–7, to end the streak, but recovered to reel off wins in the next 10 games. Though the Dolphins finished 12–2, you could make a credible case that the ’73 vintage was superior to the previous season’s. They won two playoff games to reach the Super Bowl and this time arrived as the 6.5-point favorite.

In Yepremian’s memoir, titled I Keek a Touchdown—again, the cheery self-effacement—he wrote that this Super Bowl would mark a chance to create a fresh happy memory and allowed himself to imagine the celebration. “I don’t smoke or drink, but I’ll wear one of Krikor’s cowboy hats and wave one of his big cigars.”

But, again, the Fates wrote a different script. In October of that season, Maritza miscarried a pregnancy. Happily, she soon got pregnant again. But, attending Super Bowl XIII in Houston, she felt unwell before halftime, noticed some spotting on her undergarments and went to a local hospital. When Yepremian looked into the stands during the game and saw his wife was absent, he grew concerned. A rumor circulated around the press box and wives section that she had miscarried again.

The Dolphins beat the Vikings 24–7, but after the game, Krikor found his brother. “I’m sorry,” he said somberly, “but Maritza lost the baby.” As soon as NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle presented the Dolphins with the trophy, Yepremenian found a police car to take him to the hospital.

As it turned out, Maritza had not miscarried. In July 1974, she gave birth to Garo Yepremian Jr. Another son, Azad, would follow two years later. But for the second straight year, Yepremian was hardly in a jubilant mood after the Dolphins won the championship.

In all, Yepremian played nine seasons in Miami and, along with Jan Stenerud, is generally regarded as the best kicker of the 1970s. And Yepremian kept up a public figure. He sat on Johnny Carson’s couch, and appeared on Bob Hope’s show and The Odd Couple, poking fun at himself. He starred in a deodorant commercial, the undersized, accented kicker set off against the archetypal tough football player.

More important for Yepremian, away from football, he lived his best life in South Florida. In addition to becoming a father, he helped his kid brother, Berj, come to the U.S.

Yepremian family lore: One day Berj was kicking field goals on a football field and grew frustrated. When Garo asked his brother why he was annoyed, Berj responded that he was struggling with his kicks from the far half of the field. Garo reassured his brother that if he could master kicks from inside of midfield, he’d be fine. Berj ended up going to Florida on a football scholarship and kicked for the Gators from 1976 to ’78. Meanwhile, Krikor moved to New York to become general manager of the Cosmos Soccer team.

Others took note of his story. In the late 1970s a young Danish soccer player, Morten Andersen, came to the U.S. as an exchange student and, coincidentally, landed in Indianapolis just like Yepremian had. The trail blazed, Andersen went on to Michigan State and then on to the NFL—without his brother having to write letters to teams. “He was in many ways a pioneer,” says Andersen. “He had an immigrant’s perspective on football and brought his skill to the game.”

Garo went on to kick for the Saints for a season and the Buccaneers for two. In an NFL career that spanned 14 seasons between 1966 and ’81, he finished with 1,074 points and a 67.1% accuracy rate. There are currently only two pure kickers in the Pro Football Hall of Fame: Stenerud and Andersen. It’s not hard to make a case that a third foreign-born kicker, Yepremian, could have joined them.

After football, the family stayed in South Florida for a decade and then moved to Philadelphia, where Maritza had grown up. Yepremian was a regular speaker at corporate events, delivering to the employees of IBM or Honda or Xerox a simple message: This is America, land of freedom and opportunity. If I can make it here, so can you.

Inevitably, members of the audience would ask about “the play.” He smiled and answered. When the Wounded Warrior Project asked Yepremian to re-enact his gaffe for a fundraiser, he obliged. Speaking to the excellent South Florida columnist David Hyde, Yepremian put it this way: “It got old talking about it after the first week … but you have to have a certain kind of personality to live with it. If I didn’t, I would have gone into hiding and never played again. … You have to take a negative, forget about it and build a positive from it.”

In the early 1990s, Yepremian ventured to Miami to play in a Dolphins alumni golf event. At one point, he approached Shula and told him how deeply he appreciated that letter that had buoyed his spirits during a difficult time. “You’re welcome,” said Shula haltingly. “But I never sent you a letter.”

Some in Yepremian’s family believe that was the coach denying his softer side. But that day, the two men raised the prospect that the note may have come from Shula’s wife, Dorothy, posing as her husband. Dorothy had recently passed away from cancer. Considering the possibility, both men stifled tears.

Yepremian stayed in touch with some of his teammates. Others remained resentful of both his blunder and his handling of the aftermath. In a 2007 interview with ESPN, Shula said, “[Bob] Kuechenberg still wants to kill him. He says, ‘That guy’s making a living off a stupid mistake that almost cost us the Super Bowl.’”

And Yepremian did not share his teammates’ schadenfreude, uncorking champagne when other undefeated NFL teams lost. Here’s Kuechenberg in 2002 when the Dolphins—the Dolphins—flirted with greatness. “Please don’t misunderstand. Current players … alumni … we’re all part of the Dolphin family. In fact, we’d like nothing better than to see the Dolphins of today carry on the great tradition we established in the ’70s. Having said that, however, if they were, say, 15–0, I’d have no problem setting Ricky Williams’s hair on fire on game day.”

Garo Jr. recalls that his father’s perspective was considerably different: “His attitude was I’m proud of that season, but records are made to be broken. Sooner or later another team will [go through a season without a loss], and that’s fine.”

Ensconced in the Philly suburbs, Yepremian took great pleasure raising his family in the kind of fiercely conventional setting he didn’t know as a kid. He played golf. He took up painting. He took on business ventures, some more successful than others. His sons were both high school kickers of distinction, but Garo took more interest (and pride) in their doing what he did not, going to college.

All this Americana calm was broken in the 1990s. Azad Yepremian was in high school when he met his girlfriend, Debby Lu. They stayed together in college, though they attended different schools. In ’98, Debbie was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor. So Azad and Debbie got married. And Garo inaugurated the Garo Yepremian Foundation for Brain Tumor and Catastrophic Illness: Assistance and Research. He wrote a book and gave the proceeds to the foundation. When he spoke, he sometimes told the sponsor simply to wire the fee directly to the foundation. He sold his paintings to benefit the charity. To his family, Yepremian was simply acting consistently with his lifelong mode of being, leaning into regrettable situations.

Lu died of brain tumors in 2004 at age 26. “What’s scary is that more and more people are affected by brain tumors and brain cancers,” Yepremian said at the time. “Could it be the water? Or because of the modified foods? Or because of all of the electronics we use? Nobody knows yet.”

A decade later, Yepremian complained about headaches. He was diagnosed with high-grade neuroendocrine cancer. It had started in his abdomen and spread to his brain, metastasizing slowly, then suddenly. He died May 15, 2015, at age 70. In his room at Riddle Hospital in Media, Pa., he was wreathed by friends and family that had grown to include four grandkids. “Even on his deathbed,” says Maritza, “he was trying to be funny.”

Says Morten Andersen: “His endearing personality and family values taught us all to live life passionately with great energy and a self-effacing attitude.”

Two years before Yepremian’s death, the surviving members of the 1972 Dolphins attended a ceremony at the White House, commemorating their undefeated season. Both a notable sports fan and notable dispenser of good-natured grief, Barack Obama spotted Yepremian and smiled as he handed him a football. “Can you still throw it, Garo?”

According to Garo Jr., his father responded good-naturedly, “Well, I’m one-for-one. The highest-rated quarterback in the Super Bowl.”

With that, Obama began running a route down the corridor of the Blue Room. Yepremian, as ever, played along and batted the ball out of his own hands, reprising his notorious moment from that 17–0 season. Obama stuck out his fingers and caught the ball.

“Now,” Yepremian said, gamely as ever, “I’m two-for-two!”

• After Surviving a School Shooting, How Does a Diver Go Back?

• Life and Times of Ryan Griffin, Brady’s Backups’ Backup

• In the World of Phoenix High School Football, ‘S— Is Cutthtroat’