ATLANTA – Throughout the Westin hotel, images and logos of the Georgia Bulldogs and Ohio State Buckeyes are sprinkled across ballrooms, convention space and lobbies. The trademark red ‘G’ is emblazoned on giant signage, Scarlet and Gray is peppered along the walls, and the branding of the event in which they are competing—the College Football Playoff—is plastered alongside.

There’s something else, too: A giant peach garnished with the letters “Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl.”

Sometimes, the latter is forgotten.

“This is not bowl week,” Ohio State offensive coordinator Kevin Wilson said here Tuesday. “This is playoff week.”

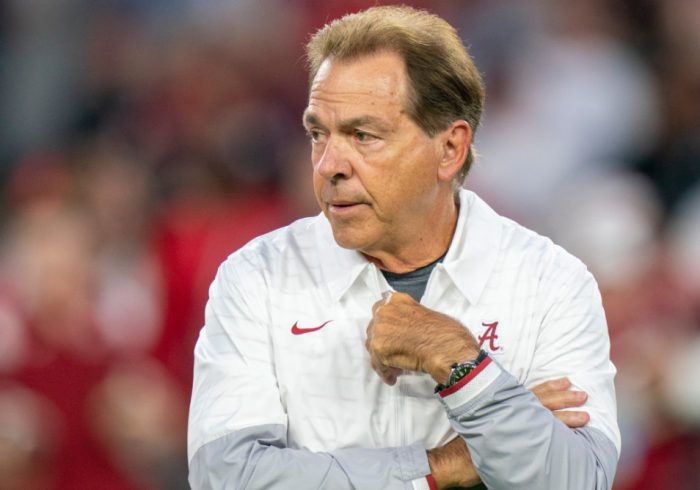

It is all a reminder of the complicated relationship between the College Football Playoff and the bowls—an affiliation made more murky with the impending expansion of the CFP. That’s why this offseason is one of the most critical for the future of bowl games than any before it, says Nick Carparelli, the executive director of Bowl Season, the organization that operates the 41 bowl games.

“There’s more drastic change going on in college athletics than I can ever remember and maybe ever in its history,” Carparelli says. “It’s time now to shift our focus to Bowl Season and determine what role we play in the college football calendar. Everything else in college athletics is evolving, Bowl Season will evolve as well.”

Carparelli and bowl officials plan to meet with conference commissioners this spring to explore significant changes that could revolutionize bowl games and pave the way for the future of college football’s postseason. Serious change appears on the horizon, Carparelli says, as bowls work to evolve in the current climate of college football.

With the College Football Playoff set to expand, bowl executives are set to take a fresh look at the entire postseason system.

Jerome Miron/USA TODAY Sports

Executives are expected to examine a great number of bowl-related issues, including stiffening the criteria for bowl eligibility from a 6–6 record; providing more standard name, image and likeness (NIL) payments to all players participating in a bowl; further incorporating bowls in the expanded playoff; shifting bowl games up a week in December; establishing more flexibility in conference bowl affiliations; and, finally, incorporating more television partners within Bowl Season.

The conversations are the first foray into what could be a years-long process of evolving the bowl slate in conjunction with the CFP expanding to 12 teams starting in the fall of 2024. Playoff expansion has further exacerbated a long-running narrative that bowls are slipping into irrelevancy, but that’s not the case, says Carparelli.

In 2021, bowl games—including CFP bowls—averaged 4.7 million viewers. That number eclipsed the average viewership for a MLB playoff game that season (3.48M). This year’s Vegas Bowl pulled in 2.5 million viewers to beat several other programs airing on the same week, including WWE Smackdown on Fox (2.2M), UCLA-Kentucky basketball on CBS (2M) and a Celtics-Lakers NBA game televised on ESPN (1.7M).

“People need to take a deep breath,” Carparelli says. “Just because some bowls don’t have an impact on the national championship, it doesn’t mean it’s not meaningful to a lot of people. Even the lowest rated bowl games have 2 million viewers, which out-rates some of the best regular season college basketball games and other alternative programming (Editor’s note: 13 bowls drew fewer than 2 million viewers last year, with the Bahamas Bowl’s audience of 851,000 people ranking as the smallest). Coaches want to play in them and 90% of student-athletes want to play in them.

“It’s not an either-or proposition: Together the CFP and bowls make up the college football postseason.”

But significant change seems imminent. In an interview with Sports Illustrated, Carparelli details the issues that he and commissioners are expected to discuss this offseason.

“The commissioners have spent hundreds of hours working on the next evolution of the CFP,” he says. “In our communications, we know that this coming offseason is the time to discuss the next evolution of Bowl Season.”

Bowl eligibility criteria

In 2010, the NCAA changed bowl eligibility to grant access to teams with a 6–6 record, a move to correspond both with college football moving to a 12th regular season game and the creation of new bowls. In 2012, the organization did the same for teams with a 5–7 record.

A decade later, college sports has set historic marks for the number of bowl participants with non-winning records. The 22 bowl teams with non-winning records last year was the most of all time. This year’s total (19) is the third-most in history. In the last two years, three teams have advanced to bowls with losing records to go with the seven that did it over a three-year stretch in 2014-2016.

Advancing to a bowl has turned from reward to expectation, some say. This year, there were 80 bowl-eligible teams and 49 ineligible, a dynamic that coincides with the increase in sponsored bowl games. There were 35 in 2010 and there are 41 today, a rapid increase that has led to officials twice putting a moratorium on new bowl games.

In nine of the last 10 years, the number of bowl spots have out-numbered the number of bowl-eligible teams, forcing bowls to incorporate those with 5–7 records.

Is it time to make bowls more valuable again and increase the standard from 6-6 to 7-5?

“That’s the conversation,” says Carparelli.

The issue has been discussed among members of the NCAA Competition Committee—whether to move the standard to 7–5 and only use 6–6 teams in emergency cases like the bowls now use those with 5–7 records. This could invariably eliminate bowl games, Carparelli acknowledges.

In the last two years, 41 teams with records of 6–6, 6–7 or 5–7 have participated in bowls—an average of 10 bowls per year.

“It’s important to remember that the bowl system is a market-driven system. No one is forcing communities to host them and conferences to participate in them,” Carparelli says. “We are hoping to find out from commissioners what the number will be. Do their teams want to participate at 6–6 or 5–7? Our system is geared for that and we can continue with that. But we’ve got to find out.”

Bowl NIL

Cheez-It, the sponsor of both the Cheez-It Bowl and Citrus Bowl, struck unique NIL deals with four players participating in their two bowl games. As part of the deal, players get access to special Cheez-It themed hotel rooms during their bowl stay that feature floor-to-ceiling items splashed in Cheez-It’s red-and-yellow branding.

“It’s like waking up inside of a Cheez-It box, but better,” a company statement said.

Bowl game sponsors are getting creative in the era of NIL, striking deals with participants that may both stave off bowl opt-outs as well as provide a work-around to the NCAA policy prohibiting pay-for-play.

This could open the door to a more standard operating procedure of bowls directly paying players, potentially steering the money paid to conferences and schools toward athletes.

“We are really eager to have that conversation,” Carparelli says. “We think we can be a great solution for the commissioners. We know they are under increased pressure to find ways to put money in the pockets of student-athletes especially with the rapidly escalating television revenue. They are not able to pay players directly. If they were to desire bowls to make payments directly to players instead of conferences and schools, we can do that.”

Several holiday college basketball tournaments have paid participating players through NIL deals. But bowl checks would be more sizable. Bowl payouts range widely, from the Bahamas Bowl’s $225,000 and the New Mexico Bowl’s $1 million, to the Quick Lane Bowl’s $2 million and the Valero Alamo Bowl’s $8.2 million.

Traditionally, payouts go directly to conferences of participating teams. Leagues then normally distribute that revenue among their members.

“The payouts from bowl games could certainly be directed entirely to the players instead of the conferences if that’s what the commissioners wanted,” Carparelli says.

Bowl executives are willing to redirect payments from schools to players, but that will be up to conference commissioners.

Jenna Watson/IndyStar/USA TODAY NETWORK

Bowls in the CFP

For months now, Carparelli has argued that bowls should be more incorporated into the expanded playoff. In the adopted expansion format, quarterfinals and semifinals are hosted by the six New Year’s Six bowl games in a rotation. But four first-round games are played in mid-December at on-campus sites of the better seed.

Carparelli plans to continue to push for a new group of bowls to host first-round games. He knows that won’t happen in the 2024 and 2025 versions of the playoff, but he hopes that commissioners will explore the possibility when agreeing to a new CFP contract starting in 2026. The CFP is in the final four years of a 12-year agreement with the six New Year’s bowls as well as ESPN. While they agreed to alter the final two years of the contract in order to expand, a new deal must be agreed to starting in 2026.

Most of the non-CFP bowl contracts also expire after the 2025 seasons, Carparelli says, opening the door for them to rewrite contracts as part of the expanded playoff.

“We continue to believe strongly that all playoff games should be at off-campus sites,” he says. “Having a competitive neutral environment is really important. Bowls are ready for a quick turnaround. They can handle it. They know years in advance that they’ll be hosting those games. And most of our bowls are located at warm-weather sites.”

The latter is important given this past weekend’s weather situation, Carparelli notes.

First-round games in an expanded playoff would have been played this past week, when a winter storm rolled through many Big Ten college towns, dropping several inches of snow, plummeting temperatures and creating harsh winds. Using the CFP’s final rankings this year, Ohio State would have hosted a playoff game, likely in 25 miles per hour winds and single-digit temperatures.

“The weather was treacherous this weekend across every Big Ten market,” Carparelli says. “It would be hard to imagine games of that magnitude being played in those conditions.”

Bowl game flexibility in dates and conference affiliation

College football’s new 365-day calendar is in the final stages of being finalized, and there’s a chance the regular season moves up a week starting in 2026, turning Week 0 into Week 1. This would allow for an extra bye week or could even shift the entire regular season up a week to provide flexibility for an expanded CFP in a tight December window.

Under this proposal, bowl games could start as much as a week earlier than normal, spreading out the 41 games over three weeks instead of two.

“If the season starts a week earlier, then it would be logical that bowls start sooner,” Carparelli says. “We are seeing some of the teams that barely qualify for bowls want to play them sooner and be home for the holidays. If the season ends earlier, we need to have that conversation.”

Conference affiliation with bowls is expected to be a discussion topic as well. Most bowls are contractually tied to two conferences, taking a designated team from each league. However, Carparelli says that could change in the future.

“Should there be more flexibility in the system where bowl games and conferences aren’t locked in with one another? Should there be more conferences involved with more bowl games?” he asks. “Some people even suggest going back to the old bowl system. That might be a stretch, but there is discussion to be had. In the old system, at the end of the season every institution is up for bid. Best teams get sought after by the bowl games with the deepest pockets. That’s how it used to work.”

Bowl TV partners

All but three of the 41 bowl games are televised by ESPN. The Sun Bowl is shown on CBS, Fox has the Holiday Bowl, and the Barstool Bowl is streamed.

Is that in need of a change? The CFP is expected to bid for the broadcasting rights of an expanded playoff starting in 2026 after the current deal with ESPN expires. The expectation is that any new version of the playoff will incorporate multiple broadcasting partners.

While 17 bowl games are owned and operated by ESPN, 24 are not, leaving the potential for other networks to get into the act of televising bowl games, Carparelli says. But it’s unclear if more bowls will find new broadcasting homes elsewhere.

“Each bowl game is in charge of negotiating their own TV contract,” he says.