U.S. Swimmers Unnerved by Latest Chinese Doping Case Ahead of Paris Olympics

As the world abruptly shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, concerns of a canceled Tokyo Olympics were assuaged when it was announced that the Summer Games would be pushed back to 2021. But that one-year delay gave rise to new fears within the United States swimming community: doping.

With drug testers unable to regularly circulate to do their jobs during that time, there was an opportunity for athletes to use performance-enhancing drugs with a vastly diminished chance of being caught. And the nation that several U.S. coaches and officials were most concerned about was China, sources told Sports Illustrated at the time.

“This greatly increases their chances of doping,” one source said in March 2020.

Roughly six months later, the World Anti-Doping Association—the global PED watchdog group—received what sources labeled an “official intelligence report” with a “specific and credible tip” about elite-level Chinese swimmers doping. The whistleblower named individual swimmers in the intelligence report, sources say.

And about four months after that, the tipster’s called shot came in: 23 of the country’s swimmers tested positive for Trimetazidine (or TMZ), a banned drug, during a meet in early January 2021. Among those who reportedly tested positive were some of the athletes mentioned by name by the whistleblower.

Nothing ever happened to the swimmers who tested positive—13 of whom went on to compete for China in the Tokyo Games, with four of those 13 winning medals. At the time, the swimming world had no idea about the positive tests, having been kept completely in the dark by WADA, which deviated from its usual policy of publicly identifying athletes who test positive for prohibited substances.

WADA accepted China’s internal investigative findings that the positive tests were the result of inadvertent environmental contamination that occurred at the hotel where the athletes were staying, citing traces of TMZ that were found in the hotel kitchen. No explanation has been offered for how the TMZ, which is used to treat heart conditions, got into the kitchen.

“It seems so egregious,” says Natalie Coughlin Hall, who won 12 medals across three Olympics, three of them gold. “During the height of the lockdown, this is exactly what everyone was worried about. It’s just a gut punch when you see something like this.”

The entire affair remained a secret until exposes were published in late April of this year by a German television station and The New York Times. WADA subsequently defended its decision not to publicize the positive tests, saying that it would have unfairly impugned the swimmers’ reputations. The drug test revelations created a cloud that will hover over swimming at the Paris Olympics next month.

“To wonder if the competition is going to be fair when you get to Paris?” says 2016 American gold medalist Maya DiRado Andrews. “That sucks.”

When those stories broke, generations of elite American swimmers felt an unwelcome spasm of déjà vu. Many of them have been through this cycle before—whether it was East Germany in the 1970s, Russia in the 2010s or China at varying points. The U.S. has had plenty of doping scandals through the years—enough to make claiming moral high ground inadvisable, if not outright hypocritical—but relatively few of the bad headlines have come in swimming.

After hearing the latest China revelations, the old U.S. swimmers were partly bitter, partly disappointed, and largely unsurprised by the never-ending story of doping within the sport.

“I’m not shocked,” says 1992 gold medalist Summer Sanders Schlopy. “I’m frustrated and I’m sad. I’m emotional for the athletes from Tokyo. I’m emotional for the athletes preparing to compete in Paris. It brought back a lot of emotions [from her Olympic experience.]”

Sanders won gold in the 200-meter butterfly in ’92, but also was favored to win both the 200 and 400 individual medleys. She finished second in the 200 and third in the 400, one spot behind China’s Lin Li in both events. Lin broke the world record in the 200 IM, part of a breakthrough, nine-medal performance by the Chinese women in Barcelona.

China’s sudden ascendance in women’s swimming prompted suspicions from competitors. “Too Good? Too Fast? Drug Rumors Stalk Chinese,” read the headline on a New York Times story from those Barcelona Games. None of the Chinese swimmers tested positive at those Olympics—but the country’s swim program would be immersed in scandal in the years that followed.

A month after dominating the 1994 World Championships in Rome, seven Chinese swimmers tested positive for steroids at the Asian Games. That led to the nation being voted out of the ’95 Pan-Pacific Championships by the U.S., Canada, Australia and Japan. In 1998, a Chinese swimmer arriving with the rest of the team in Australia for the World Championships was found to have 13 vials of human growth hormone in her luggage. Four other Chinese competitors tested positive at the meet.

Those revelations only reinforced the feeling that Sanders had in ’92, when Chinese athletes won a lot of medals without testing positive. Was the performance in Barcelona the undetected beginning of a Chinese cheating wave?

“I see myself as a 19-year-old kid, sitting on a dais in a media room looking at a sea of adults,” she recalls. “And I'm asking myself, Is anyone thinking what I'm thinking? The only thing I could do is trust the system, as a 19-year-old kid. People still say to me, ‘You should have two more gold medals.’”

Twenty years after Sanders was left to wonder what was going on, 16-year-old Ye Shiwen of China won the 400 IM at the London Olympics and broke the world record by more than a second in the process. Ye’s freestyle split of 58.68 seconds over the final 100 meters was more than 3 1/2 seconds faster than that of the previous world-record holder, Australian Stephanie Rice. More notable at the time, Ye’s 100 free split was just .03 slower than that of men’s gold medalist Ryan Lochte, and Ye actually was faster over the final 50 meters (28.93 to 29.10).

“That last 100 meters was reminiscent of some old East German swimmers, for people who have been around a while,” said John Leonard, executive director of the World Swimming Coaches Association at the time.

Ye, who also went on to win the 200 IM in London, has never tested positive for a banned drug. She has remained competitive internationally, but has not won another Olympic medal since then. She is qualified for Paris in two events, the 200 IM and 200 breastroke. According to the World Aquatics database, she has never again swam a time within four seconds of her 400 IM gold-medal performance. At the 2016 Olympics in Rio, her time of 4:45.86 was more than 17 seconds slower than four years earlier, placing her 27th overall. She did not come close to making finals in the event, and she did not compete in Tokyo.

“No comment,” was the immediate reaction of American 400-IMer Elizabeth Beisel to Ye’s plummeting performance in Rio. Four years earlier, Beisel had won silver to Ye’s stunning gold.

Immediately after the race in London, Beisel wondered if she had faltered badly in her final 100 meters as Ye pulled away. Then she got her split times and saw she had swum the fastest closing freestyle leg of her career. It just wasn’t anywhere near as fast as Ye’s scorching finish.

“I heard what people were saying and I wondered, Oh my God, have I just been beaten by someone who’s doping?” Beisel recalls now. “I had many people come up to me after that race. But Ye Shiwen never tested positive and I would never accuse her of anything. I believe the results were fair, because there is no evidence they were not.”

Says fellow 2012 Olympian Caitlin Leverenz Smith, who took bronze in the 200 IM that Ye won: “In 2012 there were eyebrows being raised, and if anything it’s gotten worse.”

For evidence of that, skip ahead to the athlete dining hall at the World Aquatics Championships in Gwangju, South Korea, in 2019. And a round of applause.

Sun Yang, the most famous and accomplished swimmer in Chinese history, had won the men’s 400-meter freestyle for the fourth straight time at the world championships. At the post-race medal ceremony, Australian silver medalist Mack Horton refused to stand on the podium next to Sun, whose career had been steeped in controversy. “I just won’t share a podium with someone that behaves in the way that he has,” Horton said after the race. He had previously labeled Sun a “drug cheat” at the Rio Olympics in 2016.

The podium snub resonated. When Horton entered the dining hall at the university where athletes were staying, swimmers from around the world applauded.

Two nights later, Sun won the 200-meter freestyle. On the podium afterward, co-bronze medalist Duncan Scott of Great Britain refused to shake Sun’s hand. “You’re a loser, I’m a winner,” Sun told Scott after the snub.

Sun served a three-month doping ban in 2014 after testing positive for, lo and behold, trimetazidine. In 2018, Sun again ran afoul of testing protocol when it was reported that his mother instructed a security guard to smash vials containing his blood after a late-night random drug test. That case wasn’t resolved until June 2021, when he was suspended for four years (backdated to 2020) after an appeal of the original eight-year suspension. Sun is not on the Chinese Olympic roster for Paris, but said last month he intends to make a comeback.

So the China syndrome of cyclical controversy seems to continue.

“I don’t think anything can ruin our sport, or the Olympic movement, but PEDs,” says NBC swimming analyst and Olympic gold medalist Rowdy Gaines. “People hold our Olympians in a completely different light than other athletes. I’m not saying there aren’t cheaters in the U.S.—I’m sure there are. But when something becomes systemic, that’s when you worry about the health of the sport. Not specifically China, but the sport in general.”

Here in America, breaking news this month seems to highlight the starkly different approach to positive drug tests between China and the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA). On June 4, it was announced that American distance freestyler Kensey McMahon had been given a four-year suspension by USADA for a positive test in 2023.

The 24-year-old McMahon said she tested positive for Vadadustat—a medication used to treat anemia in adults with chronic kidney disease—at U.S. National Championships last summer. In an Instagram post, McMahon says she has spent months (and a lot of money) trying to find the cause of the positive test and clear her name, without success.

“The sport that I had dedicated decades of hard work towards, and all its associated opportunities, that I heard honestly, were taken away from me in an instant,” McMahon wrote. “… I’m not a cheater. I don’t take short cuts. I am incredibly conscientious and diligent with my training, diet, recovery and well-being. I was mindful about everything I put into my body. … I’ve been tested by USADA in competitions and as part of their athlete testing pool since 2016 and never had a positive test. I do believe in and support clean sport.”

McMahon says she enlisted a law firm which helped get testing for every “vitamin, supplement, hydration formula, and medication” she consumed before and during the U.S. Championships. “None were found to contain Vadadustat,” she wrote. Its presence in her system remains a mystery, she says.

Lacking proof of her innocence, McMahon’s suspension stands. This is the hard line USADA and USA Swimming walk. Does it create a level of fear for every athlete—especially in an Olympic year—about somehow testing positive in spite of precautions? Certainly. Results of competition samples drawn during U.S. Olympic Trials starting June 15 will be anxiously awaited by every athlete.

But this is the rigorous doctrine U.S. swimmers accept if they’re going to hold themselves up as exemplars of clean sport. They and other athletes in the testing pool can tell stories for hours about the rigors of drug testing.

“Ignorance is not an excuse,” DiRado Andrews says. “You’re responsible for everything that goes in your body. That goes for multivitamins and any supplements you might take. You give up an element of privacy and autonomy for the sake of integrity in sport.”

Athletes who are in the testing pool are required to document their whereabouts 24 hours per day via online forms. If testers show up to administer random tests where the athlete says he or she will be and they’re not present, it’s a violation. Three whereabouts violations can count as a positive drug test and lead to sanctions.

There are knocks on the door at 5 a.m. There are visits on vacations. Testers may show up at schools or offices. If an athlete says he or she can’t produce a urine sample, the tester will sit down and wait until that time comes.

“They watch you pee, they take your blood, they become your best friends during an Olympic year,” DiRado Andrews jokes. She said she was tested at least 30 times in 2016.

The earlier an athlete starts positing elite times, the earlier they become part of the testing regimen. DiRado Andrews says she was being educated on supplement facts at age 16. Coughlin Hall says she was first tested at age 14.

“I still have nightmares that I haven’t updated my whereabouts,” she said.

“We let people literally invade our lives to have a clean sport,” Leverenz Smith says.

For the athletes who consented to that invasion in 2021 and lost to Chinese swimmers who had tested positive in secret, there is disillusionment. (“Those are all moments these athletes can’t get back,” Sanders Schlopy says. “Even if those medals are retroactively changed, you don’t get that spot on the podium, or to hear your anthem.”)

For the athletes who could be facing those same Chinese swimmers in Paris, there is a looming paranoia. If 23 swimmers could test positive and nobody found out about it for three years, what else could possibly be going on?

“They’re disheartened and frustrated,” says Leverenz Smith, who is chair of USA Swimming’s Athletes Advisory Council and has held multiple conference calls with current athletes to keep them apprised of developments with the China fallout. “They want to be able to get on the blocks and look left and look right and trust that this is a fair competition.”

Trust is hard to have at the moment. But suspicion is poisonous as the days wind down to the most pressurized meet in the world, the U.S. Olympic Trials. If ever there were a time to stay in their own lane, literally and figuratively, this is it.

“You rely on your controllables,” Coughlin Hall says. “You can’t control who might be cheating. But there is a psychological toll this takes.”

Adds Beisel: “This story breaking before the Paris Games casts a massive cloud of doubt, but you just have to put the blinders on and trust what you’re doing.”

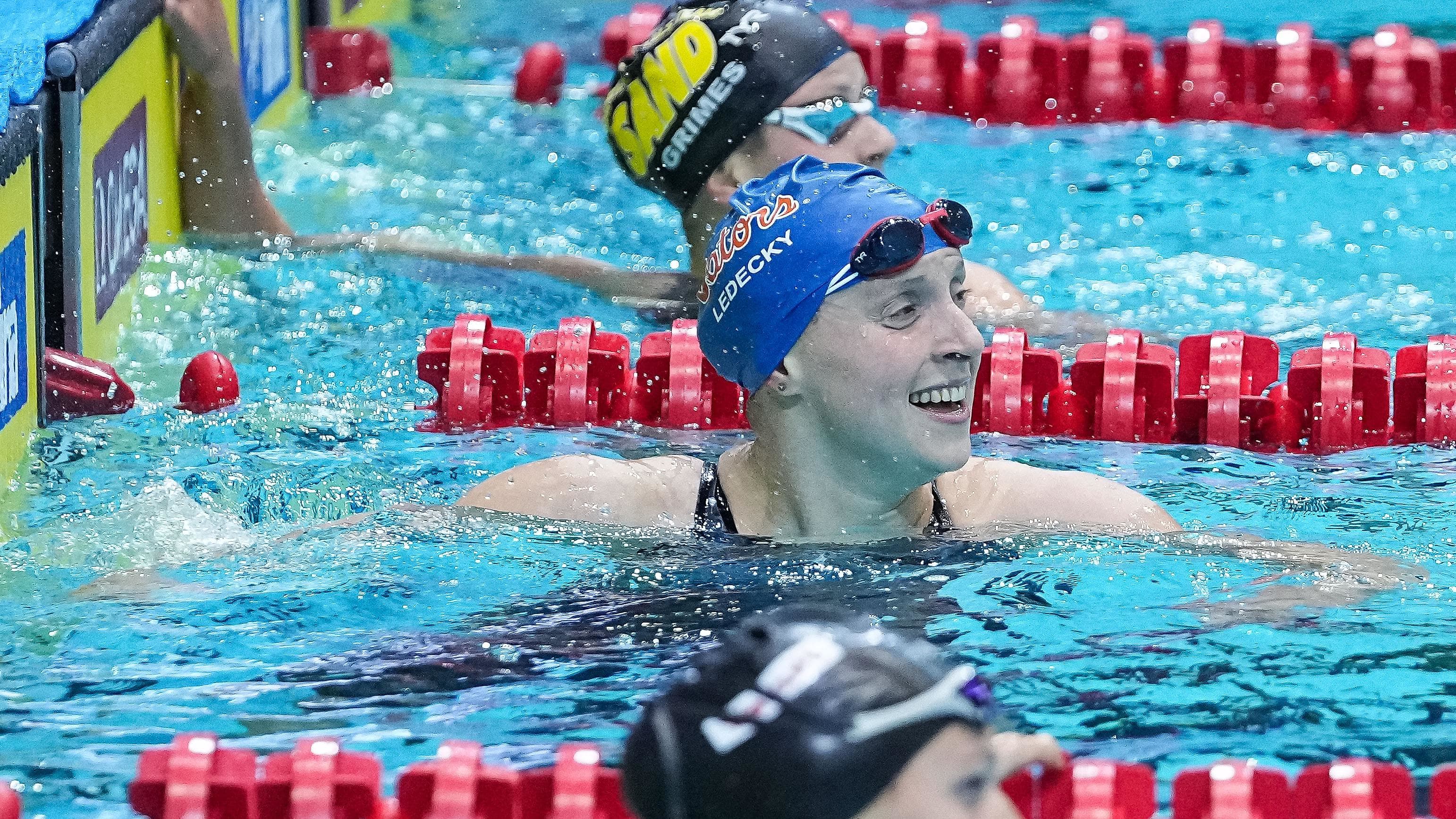

Some current American swimmers have spoken out on the issue. (“China cheated,” breastroker Cody Miller flatly declares. Superstar Katie Ledecky, who anchored an 800 freestyle relay that finished second to China’s world-record effort in Tokyo, voiced her concerns to CBS Morning News recently: “It’s hard going into Paris knowing that we're gonna be racing some of these athletes,” Ledecky said. “And I think our faith in some of the systems is at an all-time low.”)

Many others have tried to avoid it—which will be a futile stance at Trials in Indianapolis. The delicate situation has motivated many of the former swimmers to do the talking for the current generation. (The most prominent former swimmer of all-time, Michael Phelps, had nothing to say on the subject. Phelps declined to be interviewed for this story through his representatives at Octagon Sports.)

“Leading to the Olympic games, you have zero mental capacity to worry about who’s clean,” Sanders Schlopy says. “They shouldn't have to make a huge media stand to have a clean sport. It takes a once-in-a-lifetime athlete like Lilly King, who had the guts to stand up.”

King made her famous stand in 2016, calling out Russian breastroker Yulia Efimova, who twice had been suspended for positive drug tests. Efimova was supposed to be banned from the Rio Games but was reinstated shortly before the competition. King, who would race Efimova in the 100-meter breaststroke, made no secret of her disapproval.

“You know, you’re shaking your finger number one and you’ve been caught for drug cheating," King told NBC after the two competed in the semifinals of the event. “I’m just not a fan.”

King backed up her talk by taking gold in the event. Will other Americans act similarly before, during or after facing Chinese swimmers in Paris? Whether it’s processed as external or internal motivation, the fuel is there.

“I’d probably swim angry if I were them,” DiRado Andrews said. “What else can you do?”

Editor's Note: Pat Forde's daughter, Brooke Forde, was a member of the 800-meter freestyle relay team that finished finished second to China at the Tokyo Olympics.