Why the Orioles Are One Step Away From Becoming the 2016 Cubs

The year following a breakout postseason appearance, the 2016 Chicago Cubs won the World Series with six starting position players aged 26 and younger. Eight years later, the Baltimore Orioles, in the year following a breakout postseason appearance, will have five or six starting position players aged 26 and younger once Jackson Holliday returns from his minor league sabbatical with his confidence restored.

Both teams went through deep rebuilds. Both teams built their core by using high draft picks on position players, not pitchers, especially out of college. Both teams had Brandon Hyde on the staff—as a coach with the Cubs and as manager with the Orioles.

One piece of symmetry remains to complete the picture. Like the Cubs, who traded future All-Star Gleyber Torres for Aroldis Chapman, Baltimore must trade from its positional surplus to add a power arm to the bullpen. As then Cubs GM Theo Epstein said when he made the deal even with a 7 ½ game lead on July 25, “If not now, when?” The mission had grown from just making the playoffs to ending a massive World Series drought.

“We don’t win the World Series without Chappy,” former Cubs manager Joe Maddon says.

The Orioles, who last won the World Series in 1983, are in the same position. Taking Holliday off the table, Baltimore can put top prospects Samuel Basallo, Coby Mayo and Heston Kjerstad in play to get a lockdown late inning arm such as Mason Miller of Oakland or Jhoan Duran of Minnesota. The point is that like the 2016 Cubs, the 2024 Orioles are a world championship-caliber team with an obvious need and obvious surplus.

“The teams have different personalities,” Hyde says. “That Cubs team had a lot of young players and a lot of older players with almost nothing in between. [David] Ross, [John] Lackey, [Ben] Zobrist, Miguel Montero … like fatherly figures to the young guys. But in terms of the everyday players, the talent, the athleticism, the expectations they have for themselves, they are very, very similar.”

Says Yankees first baseman Anthony Rizzo, a member of those 2016 Cubs, “They’re a really, really good team that probably is going to add pitching. It’s a long season. I know we play them in the last week of September. And I expect those games are going to be very meaningful.”

With John Means and Kyle Bradish returning to the rotation this week, starting pitching is less of a priority than an elite closer, given health and command issues of Craig Kimbrel, the closer who turns 36 this month and has a 6.75 ERA in his past 10 postseason games.

Righthander Grayson Rodriguez is the wild card in the rotation. He went on the IL this week with shoulder soreness, an injury that was not a surprise given the innings jump Baltimore heaped on him last year at age 23 (+62 from his previous high), his mechanics and his elite velocity. Of the 21 starting pitchers to average 96.5 MPH or more from 2019 to ’23, Rodriguez is the 19th to break down. The only elite velocity throwers to escape the IL are Luis Castillo and Cole Ragans.

Rodriguez has the arm to be a potential front of the rotation pitcher and a difference maker in the postseason. He needs more development to get there. He needs to improve his fastball command so that he can spot a fastball when he needs to (he can’t do that now), he needs to improve his hand/wrist placement and release on his four-seamer so that he creates more ride than run and he needs to improve the timing of his delivery.

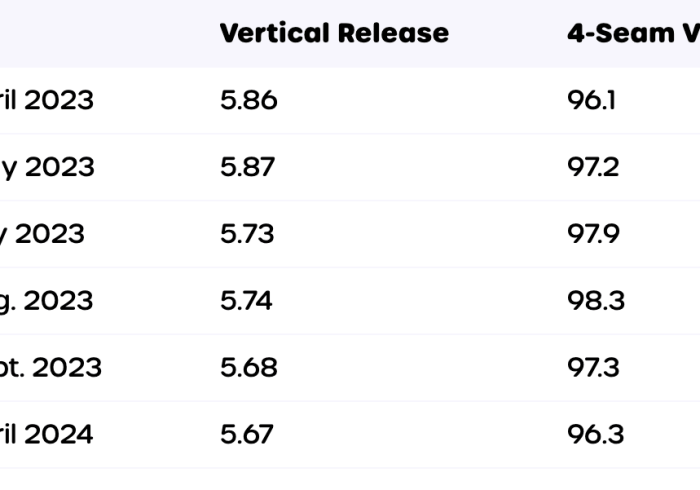

One Orioles source says Rodriguez “was gassed” by the time he reached the postseason. He gave up five runs on six hits in less than two innings against Texas in the ALCS. The attrition then and into this season shows in the data. With each month, Rodriguez’s release point and velocity have been dropping:

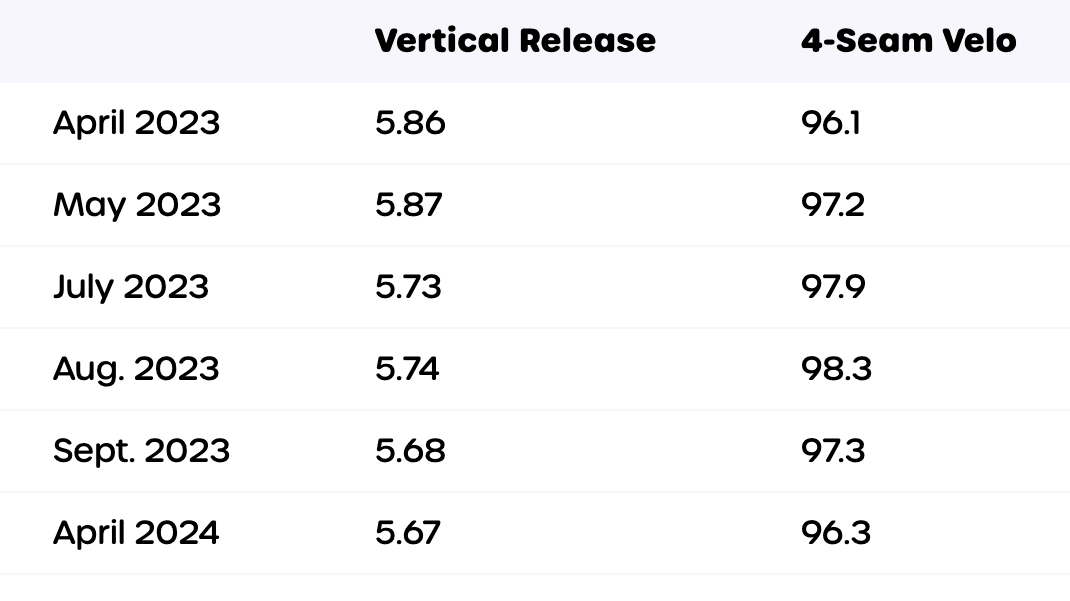

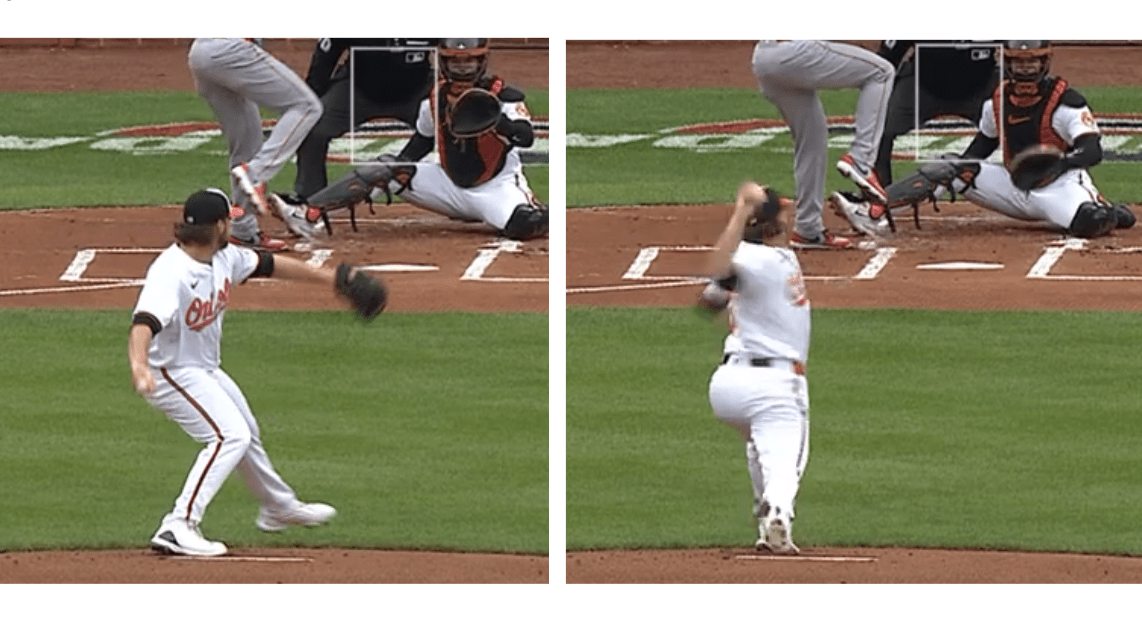

Rodriguez has a bit of funk to his delivery, which is not advantageous to a power pitcher because of the extra torque elite velocity puts on the arm. He pulls his arm stiffly behind him, pulling the ball past parallel, and does not have the ball raised with his arm in a 90-degree angle when his front foot lands, which often creates stress that first shows in the shoulder. Here’s a look at those key points in his delivery this week against the New York Yankees:

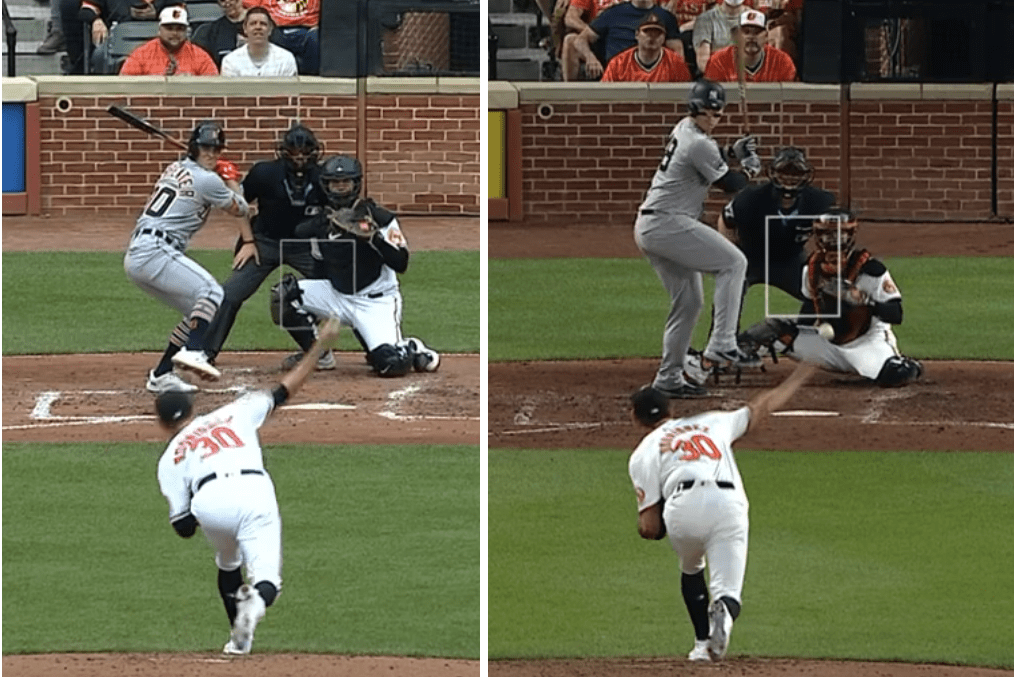

Here is teammate Corbin Burnes at those same points. Note on the left the arm position on his takeaway, as the arm is not past parallel and the elbow has begun to bend to raise the ball. On the right, the arm is at a 90-degree angle as the front foot lands.

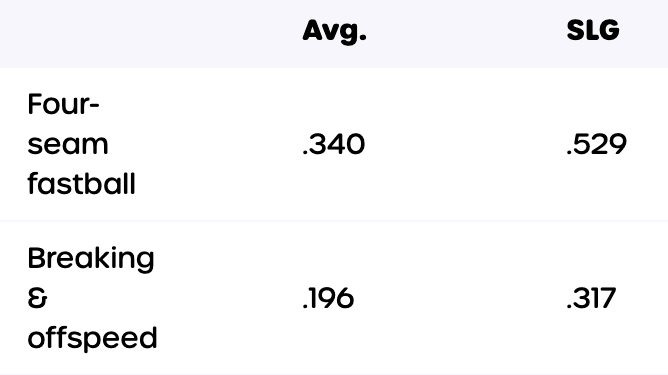

For all the talk about Rodriguez’s elite velocity, he does not pitch like a true power pitcher. His changeup and curveball are outstanding. When he needs to get back into a count or rely on a pitch in a big spot, he’s going to rely on his secondary staff. That’s a gift for such a young pitcher. But the numbers show his fastball gets hit:

Rodriguez by Pitch Type, Career

Over the past two years, 25 pitchers have allowed a .300 average or higher on at least 500 four-seamers. Rodriguez is the only one who throws 97. Among the 27 pitchers who average 96.5 and higher, Rodriguez’s .340 average allowed is 51 points higher than anybody else.

His fastball ranks in the 87th percentile in velocity this year but only in the 52nd percentile when it comes to run value. Why does such an elite velocity fastball rate as mediocre? Start with his spin rate. It is slightly below average (2,256 RPM; average is 2,288).

Another issue is the way Rodriguez’s fastball comes out of his hand. A four-seam fastball with elite ride has close to true north-south underspin to better fight gravity, causing the pitch to sink less than a hitter expects. Rodriguez’s fastball because of his hand position comes out with arm-side run. It has average drop (a measurement of “ride”) but extreme horizontal movement (“run”). A four-seamer with run is easier to hit than one with ride because it tends to stay on the same plane as the bat path rather than over it.

Rodriguez Fastball Movement

Drop: 12.9 inches; vs. Avg.: 2%

Horizontal: 11.7 inches; vs. Avg.: 60%

If Rodriguez can trade run for ride, he will have an elite north-south combination with a top-of-the-zone fastball and devastating changeup. His ceiling is extremely high.

The good news for Baltimore is it appears Rodriguez may be suffering only from fatigue rather than a structural issue. He is expected to be shut down for two to three weeks. Starting May 17, the Orioles face 43 games in 45 days. Assuming Rodriguez returns for that stretch, they will deploy a six-man rotation through that grind, just as they did last August.

“The six-man rotation last August saved our season,” Hyde says.

Like the 2016 Cubs, the Orioles are built to play seven full months. The six-man rotation is just one strategy designed to prepare for October. Another is a firm pitch limit on starting pitchers. The Orioles are adamant about getting their starter out as he approaches 100 pitches, no matter their age or experience or game situation. Dean Kramer and Rodriguez were pulled in the middle of an inning with 101 pitches and Burnes once at 100. That’s as far as any Baltimore starter has been allowed to go.

Rizzo is right to expect a close race. The Orioles and Yankees are not likely to be separated by more than three games when they meet in the last week of the season. By then, the Orioles hope to have a rotation with gas left in the tank and an additional power arm at the back of their bullpen.