Brandon Thomas wants to play on a broken foot today.

This explains everything about the hulking high school middle linebacker—but it doesn’t say exactly what you might think it says about him.

Thomas is the type who elicits fear, who loves contact and delivers jarring blows. He’s big—6′ 2″, 227 pounds—and he’s hunting for college scholarships. But as he drives to the first game of his final high school season, on the first Friday in September, he hasn’t yet transitioned into beast mode. He slows to let another car pass with a smile and a wave. He asks, “Should I turn the music down?”

Of course not! Middle linebackers don’t turn the music down!

Instead, Thomas cranks the volume on his “football mix,” blaring hip-hop and trap music, though it’s unclear whether he sees how the lyrics speak to his last two years: “I’m willing to die for this s—. . . . Hold up / Wait a minute / Y’all thought I was finished. . . . Ball so hard . . . we ain’t even ’posed to be here. . . .”

His legs pump like jackhammers, and his body rocks back and forth as he drives, the car seeming to sway with him, seat belt straining. This game is pivotal to the football ambitions of an 18-year-old with sweetest-kid-alive vibes, who’s hell-bent on total destruction and who also knows: It’s just a game. Not at all important.

At least, he knows he’s supposed to think that way, after everything that’s happened to him.

Growing up in eastern Washington, the younger of two boys, Thomas was raised in a family of athletes and academics. He wanted to be two things: a superhero—he loved Spider-Man—and a football star. His mother, Melanie, refused at first to let him play football, but it was all he ever talked about. He wanted to be like Ray Lewis: physical, aggressive, violent. She heard her son say things like, “There’s just a feeling to [football], a goosebumps vibe I can’t explain.”

In fifth grade, Melanie relented.

At Central Valley High, coach Ryan Butner loved everything about Thomas. His leadership, his work ethic, his overall disposition. Plus, the kid could play; he hit hard, patrolling the middle of a stout defense. In 2019, Thomas’s sophomore season, he earned varsity all-league honors, and he was only 15, still growing. A “recruitable athlete,” Butner says.

Three years later, on a home game day, Thomas pulls into the parking lot to find fans setting up a tailgate. And as he walks across cute little phrases chalked onto the pavement—welcome to your next adventure . . . keep going—he sheds his sweetness. Passing a stuffed bear at the entry to the locker room, he yells, “It’s going to be lit!”

Brandon Thomas wants to play on a broken foot today. But it’s not what you think. On May 29, 2020, a week short of his 16th birthday—and in the earliest, most chaotic days of the COVID-19 pandemic—his lower right leg was amputated, just below the kneecap. And this morning, four hours before he pulled into a disabled parking spot at Sarge Alberts Field, he noticed a crack in the base of his prosthetic.

“Don’t matter to me,” he says. “I’ll play on a broken foot.”

Thomas woke up around 11 a.m. on game day—classes hadn’t started yet and, well, he’s 18. Soon he was watching game film, eyes still droopy, half asleep. Eventually, he grabbed the PlayStation in the living room and cued up Rocket League, a combo soccer-and-monster-truck-rally game. Against a couch rested a pair of crutches. And there, tucked in a corner, near the front window, a statue of . . . a golden human foot?

“Oh,” Brandon said, not looking up. “That’s my foot.”

So, uh, what’s up with that?

Thomas’s uncle, Aaron Williams, made it for him. Uncle Aaron is not a professional artist. But he does have skills. After Brandon’s foot swelled to more than twice its normal size, and just before the amputation, Uncle Aaron concocted this plan: He bought a mop bucket, placed Brandon’s “gigantic hoof” inside and poured a mold mixture around it. When that set, he filled the mold with plaster, dried it, sanded it, inserted a bolt for stability, sealed it with white primer and painted his creation gold. He coated everything with a clear polyurethane and mounted it on a stone onto which he’d inscribed Deuteronomy 31:6.

Be strong and of a good courage . . .

Before Thomas lost his leg, an uncle took a plaster casting of his about-to-be-amputated foot.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

In mid-February 2020, after a routine workout with Central Valley’s track team, Thomas’s right ankle started to throb, pain shooting upward like he’d never felt before. He wasn’t the oft-injured type; even when he’d fractured a growth plate in his left knee, when he was 14, it healed without surgery. So, this? Had to be a sprain, perhaps from all the 42-inch box jumps he’d just knocked out. Maybe a fractured bone. But that heals.

After two weeks without improvement, Melanie took Brandon to an orthopedist, where a doctor, bewilderingly, said, “Gosh, you guys are having a tough day.”

Puzzled glances all around. “Not particularly? What’s up?”

“Nobody likes to hear that you have cancer.”

“Like, you’re saying he might die?” asked Brandon’s father, Devon, who’d joined the meeting on speakerphone from his commute home.

Yes.

This wasn’t just any cancer—Thomas was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, which begins in the cells that form bones but can spread all over. A few years earlier, also in eastern Washington, another teenage football player, this one with a scholarship to Idaho, had died from the same illness at roughly the same age.

What mattered most: How far had the osteosarcoma spread? If it had reached Thomas’s lungs, the odds of survival plummeted from roughly 70% to around 25%. Either way, doctors were recommending amputation of the ankle and foot, both of which Brandon assumed he needed to play football.

He looked at his mom. Eventually he would ask Why? but not yet. Instead, he said, with such conviction that Melanie had no choice but to believe him:

“If I lose my foot, it’s O.K. I just want to live.”

For now, he asked Melanie to take him back to school. He didn’t want to miss his American Sign Language class. He wanted to experience as many days as possible being anything but a cancer patient.

A week later, doctors phoned Melanie. A CT scan revealed the cancer had not spread to Brandon’s lungs. When Melanie then rang her son, and he answered in the school cafeteria, he heard her scream and, he says, “blacked out.” Classmates told him later that he nearly collapsed, tears racing down his cheeks. Melanie, on the other end, caught the whole thing; Brandon had put his phone in his pocket without hanging up.

She heard something like 50 students yelling and she thought: Maybe we’ll be O.K., after all.

Melanie and her husband, both now 42, met as teenagers at the Burger King in Jacksonville where they worked. They had a son, Josh, when they were 18, before Devon played defensive end at Louisville and later became a college sports administrator, zigzagging around, everywhere from Louisville to Idaho to Central Florida to Gonzaga, where he is now. Melanie became a college student success adviser. Josh played basketball at Eastern Washington.

In 2020, they would confront Brandon’s cancer together. He told them, “I’m gonna go crush this,” though privately he would look back at every “bad” thing he’d ever done and wonder whether some sort of karma had gotten him here. He stopped feeling like himself. And he started to recognize just how much had changed already.

Within a week, doctors had installed a port for his first chemotherapy treatment, which he received that day. He moved into Providence Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital . . . just as the pandemic began, with all of its restrictions. The gym, for one, was closed, but Thomas finagled an exercise bike for the room. Meanwhile, he watched the kids around him—most far younger, even infants—endure radiation and sores and vomiting. Some died. “The worst feeling I can ever feel,” Thomas says. “Brutal.” Still, the empathy he summoned helped him worry less about himself.

Through 10 weeks of chemo, Devon and Melanie put recovery ahead of their marriage. Josh postponed his wedding. Brandon slept at Sacred Heart for more than 85 nights and visited at least 140 days. His hair started falling out, leaving patches in his high-top fade. He held off for as long as he could but ultimately conceded to the clippers. First, though, he turned to his mom: “I just don’t want you to cut yours.”

Melanie spent every one of those nights at her son’s bedside—it was her job, as she saw it, “keeping him alive.” “Every second of every day,” she says, “you feel like you can’t breathe. Waiting for something that will make you feel O.K. . . . [Like] a normal human being.”

Finally, on May 29, not three months after his diagnosis, Brandon went into surgery. His parents had pushed to postpone the procedure so he could enjoy his 16th birthday, but he told them no. “It already didn’t feel like my leg,” he says.

On that first Friday in September, Thomas strolls into the Bears’ home locker room, his favorite place in the world. He grabs his light-blue jersey, No. 28, and tugs it over his shoulder pads. He dances. He applies eye black. He shimmies his right cleat over his cracked prosthetic.

He checks himself in the mirror. Good to go.

Inside the trainer’s office, student managers wrap tape around his wrists. Teammates are here, too, and they’re teenagers, so Thomas positions himself, as he likes to, in front of any jokes. Go ahead and tape “both ankles,” he cracks.

He’s the first player out of the locker room, the first to the stadium entrance, the first to walk onto the field. Mountains line the backdrop, but the view is cloudy from wildfires five hours away. The sun glows a bright orange as that old Phil Collins song plays over the P.A.: “I can feel it . . . comin’ in the air . . . tonight . . . oh lord.”

How in the world did Brandon Thomas end up here? It started the day of his amputation. Thomas believed, through hope or delusion, that cutting off part of his body represented his best chance to keep doing a lot of things, but none that mattered more than football.

He endured a catheter that hurt worse than surgery. He gained 30 pounds eating whatever he wanted during the first round of chemo, then lost it all. He didn’t blink when doctors told him they needed to up the dosage for Round 2 and tinker with his particular cocktail of drugs. He underwent three additional surgeries and chose to be awake for one of them. Then the side effects of the additional chemo kicked in. His first seizure hit on July 18, 2020, his second on Aug. 21, rattling him because he wasn’t in control. His body, again, didn’t feel like his own. Doctors dialed down the drugs, which only extended his treatment. He weaned himself from the steroids they offered him, which induced vomiting, so he went back on. No matter what, he couldn’t win. Not unless he made it back.

After getting an early cast sawed off, Thomas has three prosthetics now: one for football, one for lifting and one for everyday life.

Courtesy of the Thomas Family

Or maybe he wouldn’t play football again, after all. “I don’t know if I can be as good as before,” he told his brother. Josh reminded him not to look too far ahead.

On Nov. 8, Thomas underwent his last overnight chemo treatment. On Dec. 22, doctors removed his port. He went home and friends—many with heads shaved in solidarity—sat outside his bedroom window for long chats. (This was still in the early, extra-cautious days of the pandemic.) Teammates scribbled his name and number on their wristbands. They created a GoFundMe page and raised $26,000 to help cover his medical and prosthetic costs. They held a parade in Thomas’s honor, drive-by style, with a police escort, every car decked out with signs and streamers, as they chanted, “Bran-don! Bran-don! Bran-don!”

And while Thomas found himself heartened and grateful, he struggled still to find his normal, which made him uncomfortable, which led him to withdraw. He finished his last treatment on Feb. 8, 2021.

Then he met a girl. His best friend introduced the two, and Brandon played coy at first, because, he says, “I didn’t think girls would like me, because of my amputation.” But she did. They started dating.

His cancer was in remission. He stopped worrying about normal.

Cue the montage. There’s Brandon, with Josh, in that spring of 2021, working out in the backyard, doing ladder drills and sprints, adjusting to the prosthetic leg. Later, he’s next to Josh and his fiancé when they finally marry, as the best man. Standing.

Eventually, Thomas called his coach about a comeback. Butner saw no reason they couldn’t at least try, even if much recovery remained.

Among the obstacles: phantom leg pains, which came in waves. On Thomas’s personal spectrum of pain, even the least awful tremors registered as severe. But he would try anything to get back, including mirror therapy, where a reflection of his existing limb was employed to trick his brain into believing he had moved his amputated leg, the idea being to prod the brain into believing that what’s not yet true could be. After two weeks of therapy, he says, the pain subsided.

The aggressive approach of a young man who wanted to be Ray Lewis worked against him, too. In an X-ray that May, the nub below Thomas’s amputated leg showed several hairline fractures. He needed rest, so he took up swimming, which is sort of resting, to build up his cardiovascular strength and move in a way that actually felt freeing.

Progress ultimately bolstered his comfort level, and he started removing his prosthetic in front of non-family members, showing off his new limb, new life, new him. Thomas began to make—and encourage—lighthearted jokes about his amputation. He also returned in the spring of 2021 to Central Valley’s track team, competing in the ambulatory division. In only his second performance, he won state titles in the shot put (42′ 4 ½”) and the 100-meter dash (13.91 seconds)—meet records in both events, competitive against national standards.

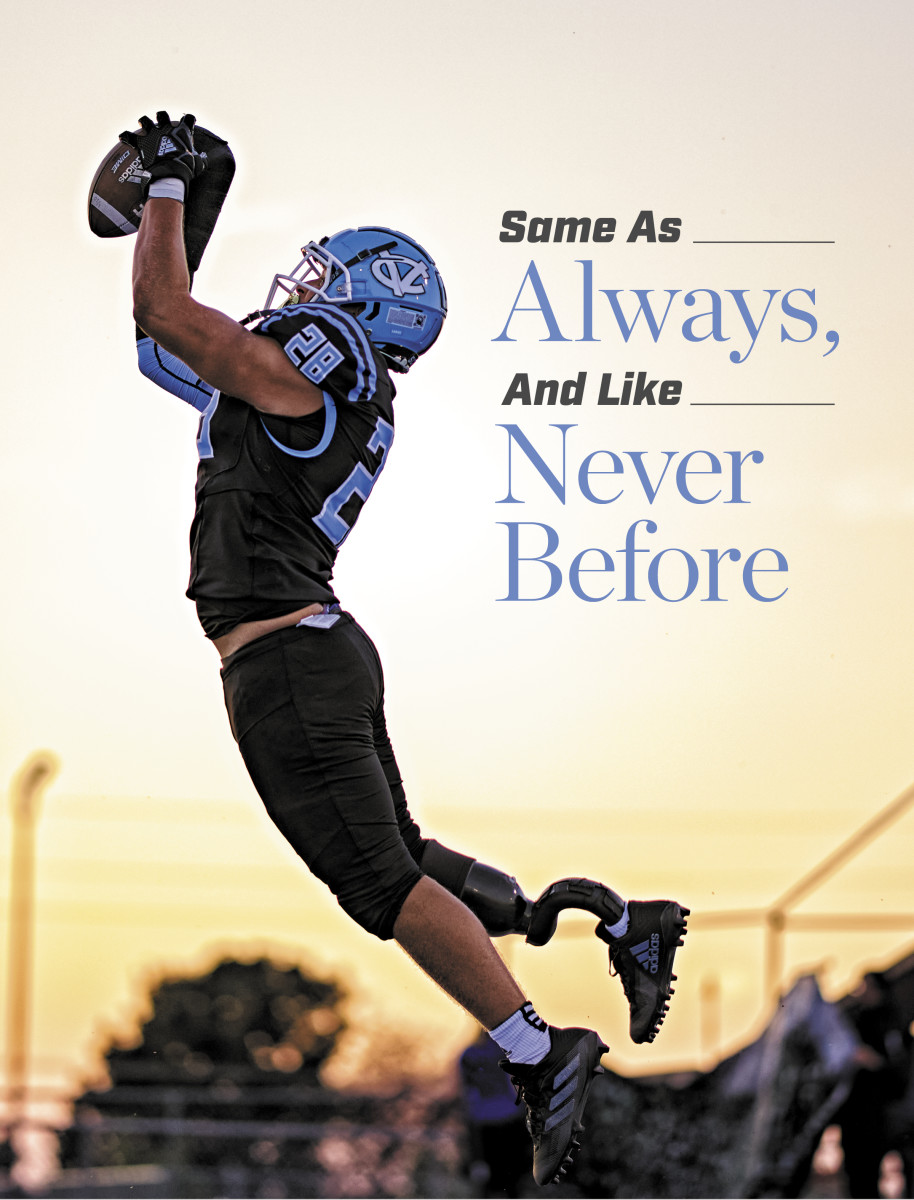

When Thomas (28) returned, Butner looked for any hint that a comeback was too much. He never saw one.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Yes, there were still moments that reminded everyone of how much work and reinforcement remained. At a volleyball tournament that Thomas participated in for fun, his prosthetic snapped in half—less scary than embarrassing, a reminder that he’d never be exactly like his classmates again. But doctors approved a return to football last fall, and there Butner found his linebacker’s attitude was unchanged, and his hits still resonated.

Playing on a new prosthetic—his “athletic leg,” as he calls it, with better flexibility and give, helping him bend and change direction—Thomas moved to outside linebacker, to limit his lateral movement. (He uses a separate prosthetic for everyday activities and another for weightlifting.) Coaches tweaked his practice schedule, adding more rest. They planned to start him after a month or so, but he cracked the lineup for the opener, and on that night he played a football game both the same as always and like never before. All season he ranked among the Bears’ top tacklers. He didn’t miss a game; he hardly missed a down. He led more often and more loudly. He scored his first career touchdown, as a Wildcat quarterback making an offensive cameo. If this were Rudy, the story would end there, the kid with one foot scoring as his career wound down in ceremony. But the score was never the point.

Butner watched closely last season, searching for vulnerability, any hint that this comeback was too much. He never saw one.

On Halloween, shortly before Thomas led his team to the playoffs, the Seahawks invited him to a home game, where they honored Brandon and made him an honorary captain. Bobby Wagner, one of the best linebackers of this era, gave him a signed jersey.

And in that moment, at that game, Thomas didn’t think cancer. He thought NFL.

Half an hour before this year’s season opener, Devon Thomas makes his way down to the field to drop off a new, uncracked foot for his son’s athletic leg. Just in case.

As his father heads back up to the stands, Brandon teeters with indecision. Inside the locker room, he sits down and holds the replacement, weighing whether to swap it in for the damaged one just 23 minutes before kickoff. He removes the cracked foot and jiggles the new one into place. He tests out his balance with a couple of steps and likes the feel. Screw it. He glances at the quote on the home screen of his phone—impossible odds set the stage for amazing miracles—and stalks out toward the field.

The sweet kid is gone now, a few miles removed—and a world away—from the bedroom decorated with Disney and Spider-Man posters. He’s no longer a “big Minions guy.” Not for a few hours, anyway.

Back at middle linebacker, his gait is a little uneven but no worse than normal after the prosthetic change. His family watches from the bottom level of the stands. He yells. Butner tells him, “You’ve worked really hard for this! You’re allowed to be excited!” and he sort of hears it.

The game unfolds slowly, unevenly, the action twice stopped for long stretches so that injured players can be hauled off toward ambulances. This rattles Melanie, who thinks the cost of football is too high. For a few minutes, she feels like she cannot breathe.

Off the field and between tackles, Thomas gets encouragement—and adjustments on his “athletic leg”—from Devon and Josh.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

But nothing fazes Brandon. He logs his first sack of the season, collects 12 tackles—four for a loss—and plays a little fullback in a 33–0 trouncing. Not bad for Week 1, especially with the pregame hiccup. He’s clearly the best player on the field.

That night, and the ones that follow, reinforce the same point: Whether or not Thomas earns a college scholarship, it doesn’t matter. But any team considering him—he’s been talking to one FBS school and more at the FCS level, plus he’ll have options in track—might want to fashion a wider calculus to account for everything he brings. Thomas survived cancer with a smile on his face and a resolve embedded deep within his soul. He holds a 3.63 GPA and will graduate with a year of college coursework already completed. He’s the best leader on his team, the best player—strong and thick, taller and heavier and still growing. He’ll only get more used to his prosthetics. “I truly believe there’s a place for him [in college football],” says Butner.

In the locker room following the opener, the coach thanks his players and tells them they “could be dangerous” come playoff time, as long as they keep improving. The room smells terrible, like sweat and ointment and teenager, but none of the players seem to mind.

That’s the good stuff. That’s why Thomas came back. In Week 2, another win, he will make 16 tackles, four for a loss, and force two fumbles. In Week 3, another win, he will return an interception for a touchdown and make five tackles, two for a loss . . . but he’ll also fracture the thumb on his right hand. He will not play the following week. He’ll beg to compete and lose the argument, just as his team will lose without him that Friday night.

Thomas should know what’s obvious: He has already won. He’s Devon’s hero—an embodiment, his dad says, of the human spirit. He’s Melanie’s greatest source of strength. He’s Central Valley’s inspiration, his coach’s hammer. He’ll continue to get scanned every six months for any signs of recurrent cancer. His next appointment is scheduled for November.

After the game, Thomas climbs back into his car and pulls out of the disabled spot. From here, he wants to play college football. And, after everything, who would dare tell him no?

• He Survived a Shooting at His High School. Returning Has Been, at Times, Unimaginable.

• Jeff Luhnow’s Next Act: Soccer

• In the World of Phoenix High School Football, ‘S— Is Cutthtroat’