Kelsey Plum dribbled the shot clock dry, then drove to the hoop, the simplest basketball act fueled by the purest of basketball motives. Last summer, the Aces retired Becky Hammon’s No. 25, and Hammon said last week, “I worked with Plum on her finishing.” Hammon was a Spurs assistant then. She says coaching the Aces “didn’t even cross my mind.” She helped Plum because it’s what coaches do. Now Plum took rock to rim; finished; did a half-pose, half-strut at center court; and returned to the bench, where Hammon and a championship were 25 seconds away.

The Aces and Sun bounced from one casino arena to another for a week, but by the end of the WNBA Finals, they both knew luck had nothing to do with this. The Aces have more high-end talent than any team in the league. They are expertly coached. They play hard and unselfishly. When time expired on their 78–71 series-clinching Game 4 win and star A’ja Wilson spiked the basketball, they were the most deserving champions.

Dynamic point guard Chelsea Gray earned Finals MVP honors for a performance that was both unconscious (she drained so many contested shots that Sun coach Curt Miller joked they should just leave her open) and extremely conscious (nobody makes savvier decisions with the ball). Sub Riquna Williams nailed three long, unflinching it’s-my-turn-now jumpers in the series’ final 121 seconds. Plum and Jackie Young showed why they would be the best players on some teams.

They all contributed, but two women carried them: a star who had to be convinced she could do anything and a coach who was always told she couldn’t.

Last spring, before Hammon ran her first Aces practice, Wilson visited her in San Antonio. Other than meeting when Hammon’s number was retired—she played for the franchise when it was the San Antonio Silver Stars—they did not really have a prior relationship. Yet they found each other at precisely the right time for both.

Wilson and Hammon went to the gym and dinner. Wilson says she was there “just to get a vibe.” Hammon, who spent years in the wine-dinner-and-conversation orbit of Spurs coach Gregg Popovich, says, “To me, leadership is about relationships. So the better I get to know them, the better I know how to coach them and get the best out of them.”

Looking back, what was remarkable about their meeting was how little needed to be said. Hammon told Wilson she would scrap former coach Bill Laimbeer’s methodical, post-heavy system for a modern pace-and-space operation. She told Wilson that she would expect her to play center on defense for the first time in her pro career, so the Aces could spread the floor offensively. She could have told Wilson she would have to wear shoes on her hands, and Wilson would have tried it. Wilson had already committed to a new approach to her career, for three reasons: “losing, losing, losing.”

Wilson has long tried to balance her desire to fit in with her ability to be great. She says, “My rookie year [in 2018], Bill Laimbeer handed me a basketball and was like, ‘This is your team.’ And I’m like, ‘I’m a rookie. I don’t know what I’m getting myself into. I haven’t even played one WNBA [game], and you’re handing me this franchise.’”

She became a great player but not a great leader: “I lose sight of who I am, because I’m trying to take care of everyone around me.” After Vegas lost in the conference finals to Phoenix, and the league’s ultimate alpha, Diana Taurasi, last season, Wilson had a realization: When you’re the most talented player on the team, trying to be the best player on the floor every night is actually unselfish. The Aces might have won the title last year if Wilson had completely bought into Laimbeer’s idea that they were her team.

“I didn’t come in thinking that I was going to get MVP, but my mindset and my mentality is 10 times better than what it was in 2020,” Wilson says of this season.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

“He saw potential in me that I didn’t see in myself,” Wilson says. “And same with [South Carolina coach Dawn] Staley. All of my coaches see that. So they kind of let me figure it out. And then I think this year, I’m finally starting to grasp what it really means … making sure my teammates understand that I’m gonna be there no matter what and I’m gonna hold it down.”

In the gym in San Antonio, Hammon watched Wilson shoot and decided she would shoot threes for the first time in her career. Wilson didn’t need to hear it—she had already decided she would fire up threes. She knew who she wanted to be and where she wanted to go. She was starting to discover that she had the right coach to get her there.

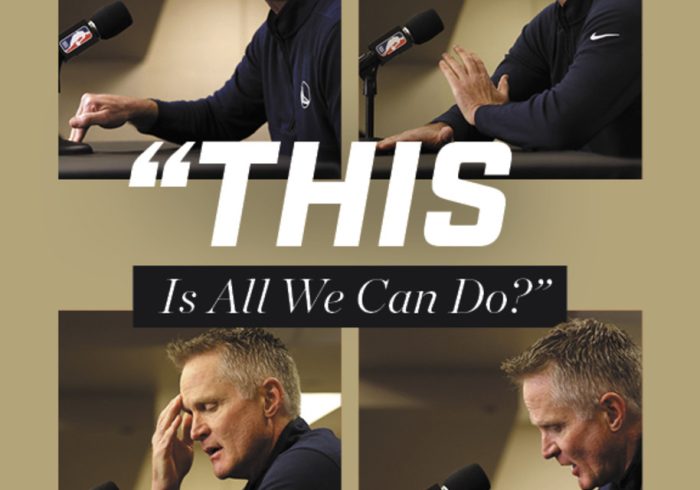

Hammon was a six-time WNBA All-Star point guard, but she did not take the UConn/Tennessee Highway to stardom. She went to Colorado State, became an All-American, and still went undrafted in 1999. Being told no so often became part of her legend, and that was before her name became synonymous with pro basketball’s glass ceiling: Time after time, she interviewed for NBA head-coaching jobs, but she never got one.

“She’s this really dichotomous character,” says one of Hammon’s best friends, Pacers assistant coach Jenny Boucek. “She’s got one side of her that is a stubborn, part-Italian fighter. You tell her she can’t do something, you’re gonna be sorry you said that. But she has this other side of her that is very strong in her faith and knows when to let life lead her. Sometimes there is tension between those two sides of her.”

Hammon had convinced the Spurs that she was ready to lead an organization. Longtime San Antonio assistant Chip Engelland, who is now an assistant for the Thunder, says, “We all knew she was a head coach in waiting. She’s ready to coach at any level she wants.” Like Popovich, Hammon is a master of making players want to hear what they need to hear. Imagine how frustrating it was, then, for her to not only get passed over for NBA coaching jobs—they’re hard to get—but have teams give silly reasons for it, like: You impressed us in the interview, but you’ve never been a head coach before.

“I’m like, ‘You kind of knew that going into this, right?’” Hammon says. “At the end of the day, if you want to find a reason to not hire me, you’ll find it. And if you want to find a reason to hire me, you’ll find that, too.”

Nobody was dumb enough to say they were wary of hiring a woman. Hammon, ever the straight talker, says it for them.

“You tell her she can’t do something, you’re gonna be sorry you said that,” Engelland says of Hammon.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

“Look: It’s scary,” she says. “You’re gonna put your billion-dollar product basically into an unknown. … At least with a man, you know it’s been done before. You hire a woman, it’s never been done before. Do you want to be the one to pull the trigger? That’s hard for people. The optics is different. The feel is different. And so it’s hard. And you know, at the end of the day, people that are normally in the hiring position are on the hot seat themselves.

“A lot of it is just the old generational mindset that women can’t lead. And then you talk about hiring a woman, hiring a gay woman … it has to be the right situation, the right group and the right feel. I don’t think it’s an experiment, but other people would be nervous because it’s never been done before. But at some point, someone won’t care that I’m a woman.”

Hammon says two years ago, she would not have taken the Aces job. But by the time Vegas owner Mark Davis called—offering what he says is a seven-figure annual salary—she was ready to embrace it.

It was clear from the beginning that Hammon would not treat the Aces as Plan B. She had a system she wanted to run and a list of assistant coaches she wanted to help her run it. Assistant Natalie Nakase, who has worked for NBA championship-winning coaches Doc Rivers and Tyronn Lue but barely knew Hammon before working for her, says she has never seen a coach as passionate about breaking down video clips at halftime as Hammon. Engelland says this desire to adjust stems from Hammon’s career-long need to prove she belonged: “That’s just how her brain works. It was never laid out for her.”

This was her chance to step out of Popovich’s shadow, but she didn’t seem all too worried about that. After Game 2, Popovich chatted with Hammon outside the Aces’ locker room. Hammon asked him to come meet her staff. In typical Pop fashion, he demurred. “They love you,” she insisted. She dragged him over to her coaches, then pulled him into the locker room.

“The way you execute, the way you play physically, it’s just beautiful to watch,” Popovich told the Aces. “Honestly. No bulls—.” He left them with one piece of advice: “Listen to what the young lady says. She knows what she’s doing.”

Hammon trusts what she sees, even if it doesn’t necessarily align with the scoreboard. Nakase says, “Even when we’re up by 20, and we start playing selfish, she’ll just call timeout: ‘Uh-uh. This is about us. This is about how we play. I don’t care if we’re up 20.’” Forward Kiah Stokes says sometimes when the Aces win, “Becky comes in mad, like, ‘We got lucky, we didn’t do this, this and this.’” At other times, “We go on a dry spurt, but she’s like, ‘We’re getting good shots. We’ll knock them down.’”

Coaches in every sport preach processes over outcomes, but so many succumb to emotions when they’re losing. Hammon is consistent—and she knows when her message is resonating. At halftime of Game 1 of the Finals, she blistered her players. But maybe the most telling moment of the series came after the Aces’ no-show in Game 3, and Hammon was asked whether she would rip them again. She said, “I got a ticked-off crew in there. I’m not going to have to say much.” Three days later, the Aces were champions.

Wilson’s teammate Gray says the 2022 MVP “absolutely” will be in the GOAT conversation.

M. Anthony Nesmith/Getty Images

Wilson has won two WNBA MVP awards, a WNBA championship, the Defensive Player of the Year award, an NCAA championship, the Most Outstanding Player award at the Final Four and an Olympic gold medal when she tied for the team lead in scoring. Although Gray was named Finals MVP, Wilson led all players in scoring, rebounding (tied with the Sun’s Alyssa Thomas) and blocks, and she played virtually every meaningful minute. She has done it all at a time when the sport’s talent pool is deeper than it’s ever been. She guards centers and forwards, but neither can really guard her.

“Not a whole lot of people have done what she’s done at the age of 26—and she just turned 26 last month,” Staley says. “She’s improving. It’s not often you see great players just improve year after year after year.”

Wilson won her first MVP award in 2020, capturing 43 of 47 first-place votes. But she says that she is “100%” a better player now: “I was just playing well, and it just happened to fall into place. But this year, I was on a mission just to be something for my teammates, to be a better player all around. I didn’t come in thinking that I was going to get MVP, but my mindset and my mentality is 10 times better than what it was in 2020.”

All three of Wilson’s coaches—Staley, Laimbeer and Hammon—were more innately feisty players than Wilson. It took a while, but she has added their edge to her talent.

“The times she’s off, I shoot her a text,” says Wilson’s best friend and former South Carolina teammate, Wings star Allisha Gray. “But so far, so good. I’ve seen the locked-in MVP A’ja, Defensive Player of the Year A’ja, since Game 1 of the season.”

After Game 1 of the Finals, Wilson laced into slumping teammate Plum, profanely telling her she was a No. 1 pick in the 2017 draft and it was time to play like it. That kind of motivational talk does not come naturally to Wilson.

“She’s afraid that she’ll lose a friend, or a teammate will not respect her,” Staley says. “A’ja is likable. She always wants to be liked. She’s now realizing [the way] to be liked is saying and doing the right thing.”

The 2020 A’ja probably would have danced around Plum’s feelings. The ’22 A’ja has more of what today’s players call a Kobe Bryant mindset; Wilson even parroted Bryant’s “job not done” line after the Aces won Game 2.

“Coach Staley was trying to instill it in me,” Wilson says. “Bill was trying to get it out of me. And now it’s out, and now Becky’s starting to guide me.”

The old A’ja showed up once this postseason—in Game 1 of the conference finals against the Storm. After a poor start, she says now, “I was trying not to step on toes. I wasn’t instilling myself into the game. I’m like, ‘I don’t want to mess it up. I’m shooting terrible. I don’t want to get in the mix.’ But that got us an L. … They did not deserve that from me. So I went back to the gym, prayed about it and got back on my horse.”

Her horse then trampled the Storm. In the next two games, Wilson scored 67 points and grabbed 24 rebounds, her best back-to-back stretch of the season.

Wilson has reached the innermost circle of basketball greatness, reserved for players who do not need to shoot well to help their team. She always rebounds, always defends, always demands double and even triple teams, and she is able and willing to pass out of them. Plum says, “A lot of times when we’re watching greatness, we don’t appreciate it in live time. We have to wait until they’re done playing.” The Aces don’t want to wait. Chelsea Gray says Wilson “absolutely” will be in the GOAT conversation. “It should already be starting to be talked about.” The Aces won the title because they knew they had the best in the world taking the opening tip—and on the bench, too.

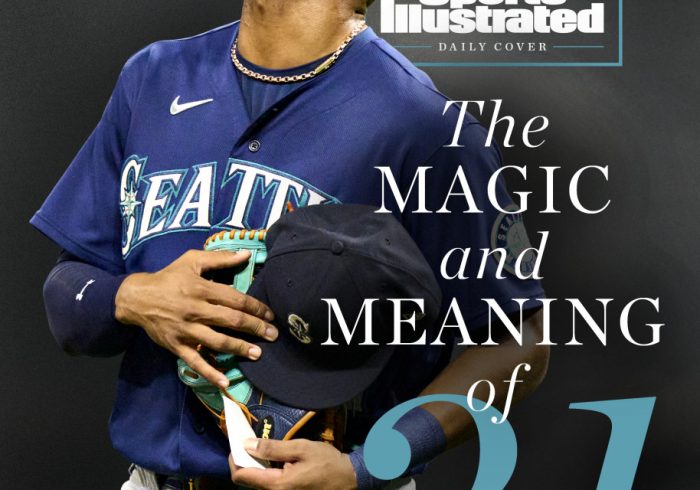

• Sueless in Seattle: Saying Goodbye to the Emerald City GOAT

• MVP. Mama. Mortician: The Many Faces of Sylvia Fowles

• She Kicked for Vanderbilt, and Then Things Got Hard