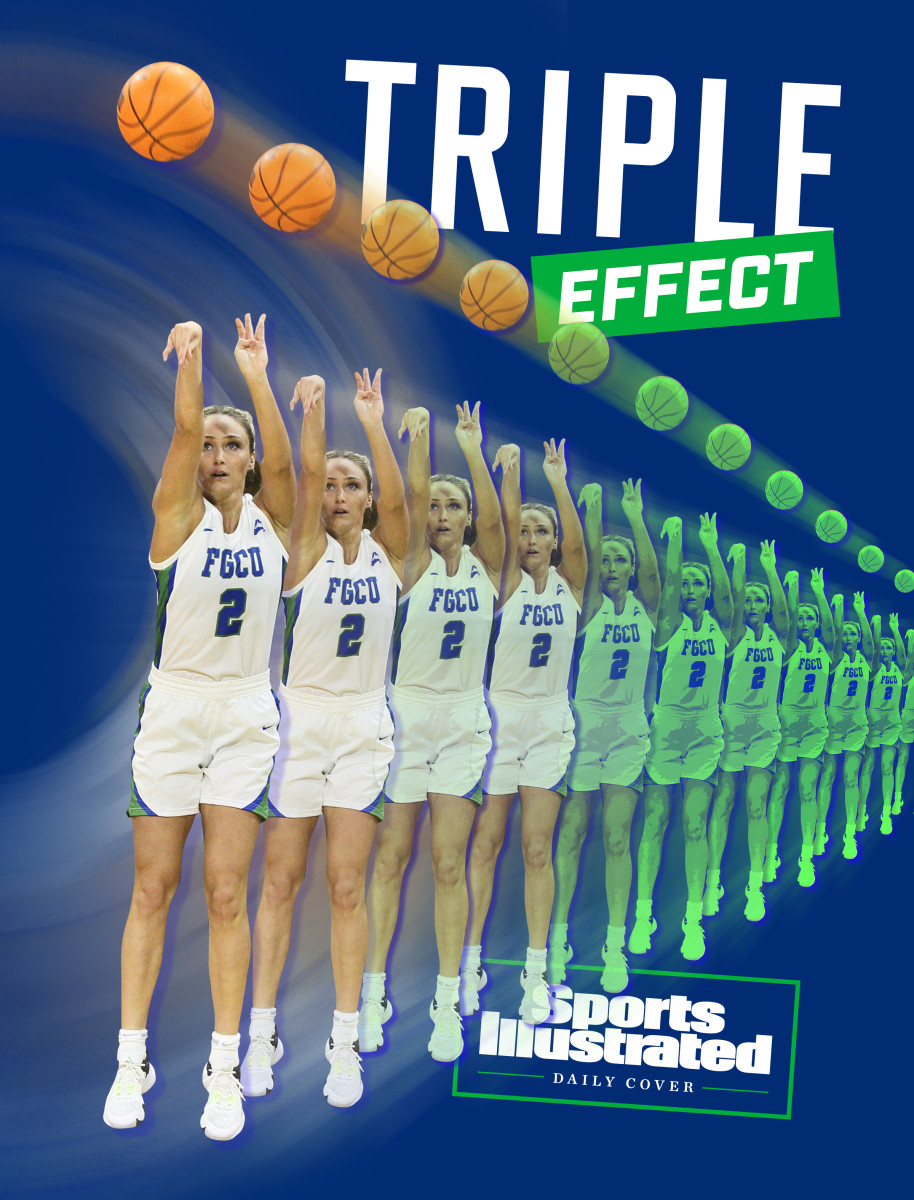

Emma List transferred to Florida Gulf Coast in 2018, and in her very first team practice, the guard did something she saw as unremarkable: She put up a midrange jumper.

Her shot was good. But the scrimmage came to a screeching halt. “Ooooh,” a few veteran teammates chorused. Their coach, Karl Smesko, blew his whistle. List was briefly confused: Before she transferred, she’d done her research, and she knew the offense here focused in the paint and beyond the arc. But surely that didn’t mean no midrange shots at all. Did it?

It did. (Or, at least, it meant: Only under a few specific exceptions.) List was about to learn: The midrange jumper does not really have a place in Florida Gulf Coast women’s basketball.

“I kind of got scarred,” the sixth-year graduate student remembers now with a laugh. “I was like, ‘O.K., noted.’ And I never took one again after that.”

Maybe that sounds like a bit of hyperbole. For a college player never to shoot from midrange again? Sure, this part of the floor is considerably less popular than it was a decade or two ago, but that doesn’t mean it’s a barren wasteland. (At least not just yet.) Even the most devoted data disciples will have some circles on their shot chart there. The midrange jumper may be diminished. But it’s certainly not dead: If it’s easy to spot teams who aspire to that kind of efficiency as an ideal, well, it’s much harder to spot those who have found a way to really put it into practice.

But then there’s FGCU—who’s been putting it into practice almost as long as the program has existed.

The Eagles were here before this style of play was trendy, before the opening battles were fought in the three-point revolution, before there was a popular understanding of the term “Moreyball.” This is simply how they operate. They’ve been among the most prolific teams from beyond the arc every year for the last decade and a half in Division I, and before that, they were among the most prolific in Division II. And, yes, “every year” means every year: There has never been a season when they meaningfully deviated from this style. The offense has necessarily evolved and adjusted over the last two decades. But it’s always stuck to the same basic principles.

At Florida Gulf Coast, you drive to the basket, you shoot from three, and unless you have a very, very good reason, you don’t take much of anything in between.

That means List’s experience from her first practice is hardly unique: FGCU players have similar memories going back years. Just ask Sarah Hansen. She’s the leading scorer in program history after taking 1,366 shots from 2010 to ’14. Now, she’s a high school chemistry teacher in Pennsylvania. But Hansen believes she still remembers every single one of those shots that came from midrange: There were five, she says, and four were thrown up out of desperation as the shot clock wound down. (The fifth was O.K., she figures, but probably still not the best shot for the situation.) “It sounds kind of crazy,” she says. “But I really don’t think that’s an exaggeration. I mean, I took a lot of shots, and out of all of those … you could count midrange on one hand.” Her time on campus started before basketball’s analytics movement went truly mainstream. But it wasn’t new at FGCU.

That’s due in large part to their coach: Smesko helped build this program from the ground up. (Almost literally: The school hadn’t yet started construction on the gym when he was hired to start the team in 2001.) This is the offense he’s always wanted to run, and at FGCU, he’s been doing it almost since the beginning. A style that looked plenty unconventional when he set it up is now widely recognized as one of the most effective in the game. It’s helped him make FGCU one of women’s basketball’s most consistently successful mid-majors: 12 consecutive seasons as either regular season or tournament champions in the ASUN, a popular yearly upset pick in March Madness, even a rare first-round draft pick in the WNBA. (FGCU alum Kierstan Bell won a championship with the Las Vegas Aces last year.) Smesko’s career winning percentage is third for active coaches—Geno Auriemma and Kim Mulkey are the only names to rank higher—and he’s hit his milestone victories faster than more than a few Hall of Famers. That naturally means there have been opportunities to decamp to a Power 5. But Smesko has so far chosen to stay in Fort Myers.

Where he now finds himself confronting a question: How do you adjust when your playbook becomes the one that everyone wants to use?

The numbers on this offense speak for themselves. FGCU currently leads D-I in three-point rate: More than 45% of the Eagles’ scoring attempts are threes. They also led in this statistic last year, and the year before, and the year before, and intermittently going back a decade. It is the only women’s program ever to finish a season attempting fewer than 30 two-point baskets per game while still outscoring its opponent by an average of double digits. And the Eagles have done it 10 times. (They’re currently on track for an 11th.) They have been nothing if not consistent: Their first season as a full D-I institution was ’11–12, and that year, they led the country in three-pointers made while taking fewer two-point shots than almost anyone. Fast forward a decade. In ’21-22, 10 seasons later, FGCU still led the country in three-pointers made while taking fewer two-point shots than almost anyone.

Or just look at their shot chart from this year:

It approaches the kind of discipline you might see in a video game—divorced from all the real-world frustrations and complications that prompt bad decisions and awkward shots. It shows that FGCU’s success does not come from making an unusual proportion of their shots. (To the contrary, their three-point percentage is an unremarkable 34.7%, and their effective field goal percentage is a good-but-not-special 53.2%.) It’s just that they’re so dedicated to efficient shot selection that they simply come at the game from a different place. It’s one thing to see a chart like this from an individual player or on a single night. It’s another to see it from an entire team over months—and the chart here really hasn’t changed too much over years.

And Smesko began thinking about it long before he came to FGCU.

The son of a high school basketball coach in Richfield, Ohio, he grew up immersed in the game, and he took an early interest in coaching. But his father’s style of play looked nothing like this. “The overall principles of how you win games, I got from him, how you lead a team, I got from him,” Smesko says of his dad, Al. “But strategically, we’re just polar opposites.” (At last, his father has come around to his embrace of the three-point shot, he says—though it took a while.) Instead, Smesko’s big epiphany came in a college statistics class. While at Kent State in the early 1990s, he started thinking more about how to apply what he was learning in the classroom to concepts like shot selection and points per possession. It just made sense to him: Why wouldn’t you try to be as efficient as possible? Why wouldn’t you run an offense based on these statistics? It reflected his personality: He’s always liked math, hated wasting time, appreciated being able to back up whatever he did with evidence. It was difficult to gain access then to the kind of basketball numbers he most wanted to see. But he noticed patterns and looked at whatever data he could find and thought: This is how a more efficient style of play might look.

That, he figured, is how he’d coach a team.

He got the chance a few years later. His first head coaching job came at Walsh University in Ohio in 1997. He’d been hired at the NAIA program as a graduate assistant while getting his master’s degree—“hired,” though he didn’t have a salary, instead getting the ability to eat in the dining hall for free in lieu of cash—and the players quickly took a liking to him. When the head coach left after Smesko’s first season on staff, the players lobbied to have their 26-year-old assistant step into his place, and he was given the opportunity.

Smesko made the most of it. He took a team that had been picked to finish sixth in its conference and made them the first unseeded national champions in the history of the NAIA. And he did it with an offense that bore a striking resemblance to what he runs now at Florida Gulf Coast.

“At Walsh, if you looked at how that team played, and you look at how we play now, is it exactly the same? No, but it’s really, really similar, and it’s based on the same spacing,” Smesko says. “The difference is there’s a lot more teams doing a lot of those concepts today than there was 20-plus years ago.”

Smesko’s style was unconventional when he set it up in 2001, but it is now widely recognized as one of the most effective in the game.

Andrew West/The News-Press / USA TODAY NETWORK

Yet that first year was an early lesson in meeting with resistance. His players were on board with his style of play: After all, they’d been the ones who’d lobbied the athletic director to give him the job in the first place, and they liked him enough to try out his ideas. But not everyone was so eager to embrace it. And some were downright baffled.

During the championship tournament, when he had to share his starters with the scorer’s table, he wrote down five guards. The response was confused: Was this a mistake? No, Smesko said. He really did want to start five guards. The follow-up was even more confused: Was this even allowed? Sure it was, Smesko said. Where did the rulebook say you had to have a big man?

“I always found that interesting, that you could be so stuck in, ‘Well, this is the way it’s always been played,’” he says. “There were a lot of other ways you could play and still be successful.”

He knew he was making some compromises on defense to run the offense he wanted. But he felt the benefit of having his best ballhandlers on the floor outweighed the drawback of going without a true post presence. And the fact that he won it all in that first season was encouraging: How could he get even more efficient? For all his belief in his system, he’d been unsure of how it would actually work in practice, wondering whether there was something everyone knew that he was missing. But if this was what he could do with an unseeded team in his first season as a head coach, scarcely older than his players, what could he do with more experience, more resources? For everyone who’d thought he was wrong … well, how’d they like that national championship?

“I was 26 years old, and I just believed I was right. And I was willing to go out there and try it, and the players were invested in it,” Smesko says. “And people from the outside who thought it was maybe the wrong way to play—you lose a lot of your arguments when we win the national championship.”

He left Walsh to spend the next year as a graduate assistant at Maryland—still his only experience at a Power 5—before spending two years as the head coach at Division II Indiana University Purdue University Fort Wayne. (His first year at IPFW was the first time he led the nation in three-pointers.) Then Smesko got a call from a school that was just getting its athletics department off the ground. The former athletic director from IPFW had left to work as an associate AD at FGCU: He thought the young coach at his old school just might have the right type of personality to lead a brand-new team. Here was the chance to start a program from scratch, with no established ideas about the right way to play, no minds to change or culture to fix. It sounded appealing.

Plus, it was in Southwest Florida, and Smesko had lived almost his entire life battling winters in the Midwest.

He came to start the program at FGCU. And he never left.

“You don’t even notice that you’re not shooting midrange,” says Morehouse, who is the team’s leading scorer.

Andrew West/The News-Press / USA TODAY NETWORK

It can be natural to look at Smesko and see someone who has stayed in place for the past 20 years: The same location, same team, running the same game plan. But his situation is more nuanced.

“I think a lot of people have the wrong idea about him,” says Shannon Murphy, who played for Smesko from 2007 to ’11 and is now an assistant coach. “He’s grown tremendously. … He never stops learning; he’s constantly reading and watching. It doesn’t matter if he’s read a book once, he’ll read it three more times to see if he missed anything. So with him, he’s constantly trying to evolve and adapt to the players that he brings in. And I think that probably a big part of the success is because he’s constantly adapting to who he has.”

That kind of evolution has been necessary as the rest of women’s college basketball has caught up with his playbook. When FGCU first got to Division I, they could lead the nation in three-point attempts with about 28 per game. A decade later, they would need 35. While they’ve consistently in the top five for three-point rate—the discipline required not to take anything between the paint and the arc goes a long way—they no longer currently lead in raw three-point attempts. There are simply too many teams trying to play a similar style.

“If there was a bell curve of teams, we were at the edge of that bell curve,” Smesko says of how it felt when FGCU started out. “But that curve was moving. So the evolution was, well, how do we stay ahead?”

That has meant refining the system with even more film, more data, more considered research. While FGCU always played a lot in transition, it now does even more. And Smesko has made adjustments around the kinds of players coming in as the program has garnered more success. Yet his assistants say his biggest change isn’t in his game plan. Instead, it’s in how he talks about it and how he presents his ideas to players.

Simply put: Smesko explains things now.

“I really think 20 years ago, it was like, Hey, these are the shots we’re going to shoot. … They’re the most efficient shots we can shoot,” Smesko says. “But there wasn’t a lot of explaining or showing.”

FGCU currently leads D-I in three-point rate: More than 45% of the Eagles’ scoring attempts are threes.

Andrew West/The News-Press / USA TODAY NETWORK

Some of that is that it’s simply easier to explain now: It’s never been more simple to access granular data or high-quality video. And as the game has caught up to Smesko, athletes come to campus with more awareness of how his style looks, meaning there’s less of a learning curve. The concepts that were once most confusing to players now feel mainstream for even casual basketball fans. During a film session in December, for instance, Smesko mixed a clip of Toronto Raptors coach Nick Nurse in with the breakdown of their last game and the details on an upcoming opponent. Two decades ago, certainly, he wouldn’t have been able to pull in a pro coach going over the same concepts he talks about with his own players. But there’s something else that’s changed: It’s not just that Smesko has more resources to reach his team or that players themselves come in with more knowledge. It’s that Smesko is more inclined to want to connect with them.

“He’s very perceptive on what works best for different people, and I think that he grew a lot with that,” Hansen says. “He changed a lot with how he handled different players in just my first year to my fifth year. … Early on, he would coach a lot of kids the same way.”

Now, Smesko is more practiced in meeting players where they are.

“It helps a lot, because I’ve been under coaches in the past where they’ll tell you to do something, but they won’t tell you why,” says redshirt junior Alyza Winston, who transferred to FGCU this season after playing at Michigan State and Mississippi State. “He’ll tell us to do something, but he’ll back it up with facts or with numbers. Like, he’ll tell us, ‘This is why I want you to do this.’ And that makes it a lot easier to respond.”

That’s made a world of difference for a player like Tishara Morehouse—who is currently the team’s leading scorer as a fifth-year senior but originally had some trepidation about playing in this offense. At 5’3″, she’d always been a scrappy player who used her speed as an advantage, and she loved how fast the team played. But the midrange jumper had always been a big part of her game. It was daunting to think of cutting it out. Yet after some time under Smesko in Fort Myers, she realized it didn’t feel like getting rid of her midrange, specifically. It just felt like learning to see the game through a new lens and playing differently as a result.

“You don’t even notice that you’re not shooting midrange,” Morehouse says. “His techniques—you’re not realizing them as you play. Like, you’re just playing basketball and making good decisions. That’s a lot of what’s in his book and his criteria—just making good reads, good decisions, saving space, seeing your space, attacking that space.”

The resulting discussion can sound almost metaphysical: “I never really knew how much space meant until I got here, and how it can be created and how it can be destroyed,” List says. But philosophical musings aside, it shows the offense has grown to be something bigger than just the data, or the three-pointers, or Smesko’s original ideas from his statistics class at Kent State. It’s a whole ecosystem—one he built from scratch.

Which is part of why he’s chosen to stay all these years at FGCU. He turned down the head coaching gig at USC in 2017 and other years had interviews with Indiana, Illinois and Oregon State, among others. He realizes that major conferences would come with more resources; he knows that despite his belief that FGCU can make a deeper run into March, realistically, a national championship is a long shot. But this is the program he’s grown from nothing, and it’s where he’s grown as a person, too. And, of course, a campus half an hour from the beach is a hard place to leave.

“There’s the quality of life—it’s a beautiful place— but it’s also his baby,” Murphy says. “When you dedicate your entire life and pour everything you have into it, I’m sure it would be hard to walk away. … And, you know, obviously, we’re always at a disadvantage when it comes to resources with the Power 5s, but we still compete at a high level. And I think that’s something that keeps driving him.”

Even when it means changing to stay ahead of the curve.

“He’s not stuck in his ways,” says associate head coach Chelsea Lyles, who played for Smesko from 2008 to ’10 and has been part of the program ever since. “He’ll evolve on a lot of things. … He’s always evolving.”

That’s true for all sorts of matters: Smesko’s defense, his coaching methods, his strategies for relating to players. There’s just one exception: Don’t look for any midrange jumpers.

“I mean, not shot selection,” Lyles says. “That’s not going to change.”